I was late to the party. Literally and figuratively. A few weeks ago, I walked in late to the Festival O19 kickoff party hosted by Opera Philadelphia on the 19th floor of The Bellevue Hotel. I could barely snake a path into the lounge for all of the millennials packed in cheek to jowl.

I threaded my way through the crowd of gen-Yers, performers, Opera Philly staff and the occasional middle-ager. These weren’t the elder folk long associated with Philadelphia’s traditional opera scene, they were 20- and 30-somethings in Warby Parker glasses and practical fast-fashion chatting about the festival’s four-show lineup. Some slurped the on-point tequila cocktail, “Semele’s Endless Pleasure,” while discussing director James Darrah’s upcoming production of Semele, while others enjoyed pints of Flying Fish Brewery’s opera ale.

Who were these fans? Why were these fans? It’s as if I’d put down a book about opera I’d grown bored with back in the 1990s, picked it up again in 2019 and the whole story inside had changed. Had opera in Philly become edgy? Was it the place to be?

I recently came across a delightfully dramatic assertion by Andrew Grossman, a critic for the website Pop Matters who noted that “the very existence of opera in 21st-century America seems a defiant anachronism, a magnificent corpse that, inexplicably, still breathes.” But, one wonders for how long this 400-year-old art form can continue to drag its heft down a strictly traditional path. The data produced by a 2014 research grant from The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage and The Barra Foundation for Philadelphia’s company predicted that a new direction was imperative.

“Figuring out a way for song to have agency, which opera has, means it’s relevant,” Devan says. “You’re already hardwired for musical expression through voice. It’s not about me selling you opera. Opera is already in you.”

The refrain “adapt or die” haunts many performing arts organizations, so it’s fascinating to find one that heeds the warning, discovers what it needs to do—and then actually does it. The hazards are familiar—shrinking philanthropy and foundation support, aging subscriber bases, increasing costs of operation, frugal and risk-adverse young potential ticket buyers—yet many organizations persist in using the same approach and simply hope audiences who drifted away will magically reappear.

So this is how I’m figuratively late to the party: Festival O19—September 14th to 29th with 29 performances in various venues—marks the third year into this radical endeavor undertaken by Opera Philadelphia to remake, rebrand and revitalize itself. It’s a mission embraced as the world of opera teeters on the brink of irrelevancy and insolvency. Somehow I’d missed the inception of this remarkable transformation. So is it working?

New York Times critic Zachary Woolfe wrote last year that Opera Philadelphia “has swiftly become one of the most creative and ambitious in this country.” In Mad Scenes and Exit Arias: The Death of the New York City Opera and the Future of Opera in America, Wall Street Journal opera critic, Heidi Waleson, wrote that the 017 festival was “an artistic triumph.” And F. Paul Driscoll, the editor-in-chief of Opera News, told me recently that the company’s “brand overhaul has been absolutely successful.”

“What Opera Philadelphia has done in terms of content delivery, establishing a festival, developing new work, establishing relations with new composers, directors, librettists, artists—it is on the forefront of American companies,” Driscoll says.

Attend O19Do Something

Devan, who was executive director at British Columbia’s Pacific Opera Victoria arrived at what was then called the Opera Company of Philadelphia in 2006, as managing director, and assumed control in 2011. (Two years later, the company rebranded as Opera Philadelphia.) Devan didn’t set out in his new post with wild visions of setting the old programming model up in flames. But he did have a mandate to make opera in Philadelphia relevant, and thriving, again. That meant, he says, coming up with an artistic practice different than New York City’s performing arts behemoth, the Metropolitan Opera Company, an easy train ride away, and celebrating “the sophistication and grit of Philadelphia.”

From Devan’s early days in Philly, the opera company seemed to be doing everything right. The quality of work went up. In 2015, the company commissioned Charlie Parker’s Yardbird, which got good reviews and has gone on to be produced elsewhere; Breaking the Waves, co-commissioned in 2016, became a critically acclaimed sensation that has been performed by companies in the U.S. and abroad. Philanthropic dollars followed. But still, the opera wasn’t seeing a fundamental change in its audience. “That’s when we started thinking that if we don’t make a big move, there’s not a path forward,” Devan says.

Opera Philadelphia calculated that its future lay in leading the way in new works, and using a festival to capitalize on the excitement generated by premieres. Thus was born an urban opera festival. It addressed the wane of subscription purchasing (millennials are single-ticket buyers and tend to dislike the longterm planning and the price tags required for subscriptions) and would give those sought-after new consumers a binge-watching opportunity to see edgy new unexpected work that mirrors the media consumption patterns they practice in daily life.

The first year, Festival 017 had five operas—some sold out in atypical venues including the Barnes Foundation and the Philadelphia Museum of Art— and earned $1,290,000 in ticket revenues. Eighteen percent of the audience was under age 29. In 2018, the schedule of performances shrank from the prior years’ 31 down to 24. (This year’s number of performances is up to 29, but the number of productions is down to four.) One-third of attendees for both 017 and 018 festivals were first-time ticket buyers, and 40 percent of 017 attendees came back to 018. Ticket buyers came from 47 states in 017 and 40 states in 018. Both festivals attracted opera fans from around the globe—Amsterdam, London, Madrid, Paris, Rome, Vienna, Dubai and Tokyo.

Andrew Grossman, a critic for the website Pop Matters, noted that “the very existence of opera in 21st-century America seems a defiant anachronism, a magnificent corpse that, inexplicably, still breathes.”

“Philadelphia had a very traditional opera audience,” Driscoll says, “an element of that still exists, but life has moved on, the audience redefined itself, the city and the industry has redefined itself too—and Opera Philadelphia has responded to that.”

Festival tickets range from $20 to $299, but there are a lot of discounted seats, too—including the free tickets for the September 14, 7 pm screening of the company’s 2018 La Boheme at Independence Mall. There’s also a 50 percent discount for kids 18 and younger and Student Rush starting two hours before a show where they could score certain last-minute seats for as little as $10. The young professionals program also offers a $35 ticket for those under 35 for certain shows.

The festival format gives ticket buyers different operas that they can pick from: Philip Venables and Ted Huffman’s conductor-less Denis & Katya speaks about social media and the disturbing extremes of voyeurism; Prokofiev’s rarely-performed The Love For Three Oranges from 1921 is a big, fun farce that might be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see; Handel’s Semele is a Baroque work with a stellar cast and creative team that delivers a stylized approach to an erotic work that feels intently modern; and Joseph Keckler’s Let Me Die is a sardonic cabaret-style exploration (and FringeArts collaboration) of opera’s fascination with death.

Watch the O19 trailerVideo

Devan frequently describes this festival model as a response to television binge-watching trends. The opera solution to our boundless appetite for immediate entertainment is to deliver a feast of provocative, relatable performances in a condensed period of time—not unlike this month’s Fringe Festival, or October’s Mural Arts Month. It becomes an event. Plus, the pop up festival happy hours and the after-hours cabaret, Late Night Snacks, give patrons a place to connect over what they’ve seen —and, for the unconverted, a place to check Eagles scores while having an opera beer and snack (Federal Donuts has created an official spiced-cake donut with dark-chocolate and coffee glazing with a sprinkle of chocolate-coffee crumble.)

Not every opera has been a hit, but Devan is unfazed. “Perfection in performance is not the goal,” he says, “rather, the most exciting and most artistic experience is the goal.”

Yet people are fickle—even with the lure of a doughnut and new work—and they often move on to the next Instagrammable event. How do you keep people coming back? Devan’s answer: It’s all about the art.

“Our job is to excite artists and audiences in that order,” says Devan. “You have to move the genre forward in a compelling way in order to attract and serve an audience…. How do we stay out in front? The answer is working with the coolest, best, most inventive artists.”

Being freed from the constraints of standard rep has allowed the art form to feel a lot more relevant. Opera Philadelphia has commissioned work about the 1985 MOVE bombing in West Philadelphia (We Shall Not Be Moved), about Alzheimer’s disease (Sky on Swings), and in this year’s upcoming Denis & Katya, the real 2016 story of two Russian teens who live-streamed their standoff with Russian Special Forces that ended in their deaths.

Devan has no hand in curating the festival. It has no theme and is just a collection of projects by talented artists. He leaves the ideas to the composers, librettists, directors, and others to point the way. OP acts as a kind of midwife to new opera. Opera Philadelphia’s New Works Administrator, Sarah Williams, takes the lead in helping the operas through the different phases of development.

“It’s about challenging an art form and a system that doesn’t often get challenged,” says Williams, a formally trained singer herself who experienced firsthand the frustration with an industry that is not inclined to evolve. “There’s a great deal of personal satisfaction in taking my own frustration with issues that held back incredibly talented, visionary people and to work here and create the New Works practice and see it flourish.”

Amanda Forsythe, who plays the titular character in Semele, is about ten feet away facing me. Her brown hair is tied up in a loose ponytail. The light lyric soprano is wearing a blue hoodie and a floor-length skirt. Twenty members of the chorus encircle her as they rehearse in the Kimmel Center’s black box basement rehearsal space. Director James Darrah instructs some of the singers to needily grab her hands and others to crouch in front of her. She’s diminutive and the men and women of the chorus appear as if they may swallow her up as she looks to the ceiling/heavens. Forsythe marvelously delivers her lyrics with her voice brilliantly skittering up and down Handel’s musical score, like someone in Philadelphia dodging ginkgo berries on a sidewalk.

Arts stories by Sarah JordanRead More

“At the greatest moments in our lives—when we get married, when someone dies, a birthday, when we have something to celebrate—we sing,” Devan explains. “That’s what we do as humans. So figuring out a way for song to have agency, which opera has, means it’s relevant. You’re already hardwired for musical expression through voice. It’s not about me selling you opera. Opera is already in you.”

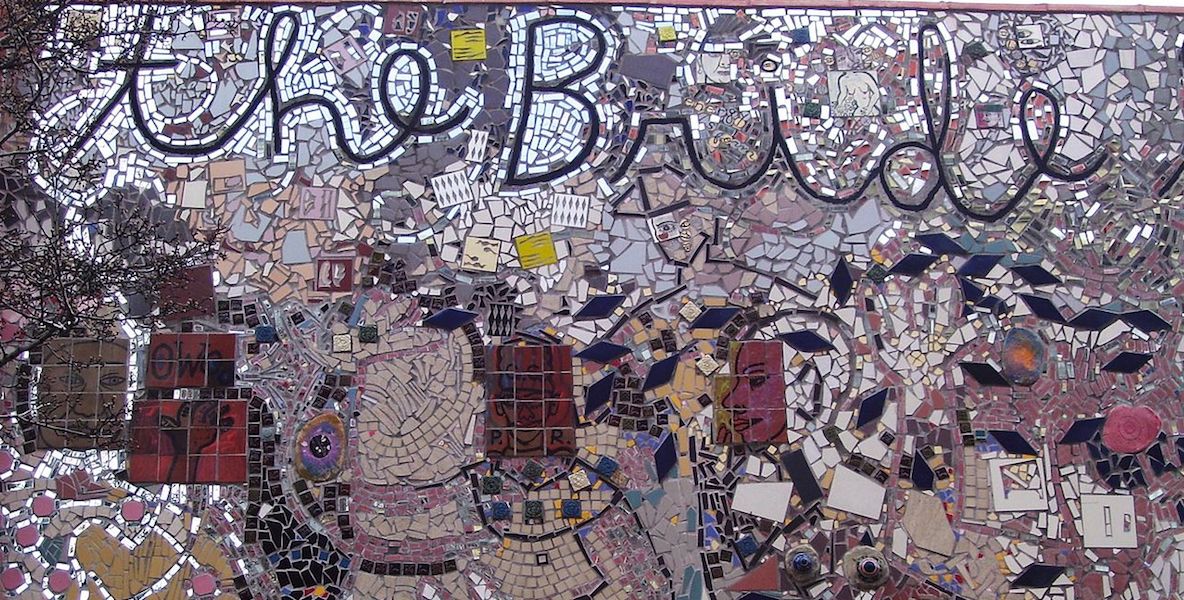

Photo courtesy Opera Philadelphia