When Jeremy Rogoff was a first year teacher in the rural Arkansas Delta, he faced all the same challenges as new teachers everywhere—knowing how to manage a classroom, keep students interested, ensure they were understanding the material. He also faced another challenge: He was the only high school Algebra and Spanish teacher within 100 miles, so he had no one to ask for help.

Be Part of the Solution

Become a Citizen member.In his two years in Mississippi, Rogoff’s professional development consisted of occasional group instruction at a central location, often on things that were irrelevant to his classroom—like how to use a SmartBoard, when his own SmartBoard didn’t even work. With no instructional coach to speak of, Rogoff says he spent hours in the evening creating lesson plans, without much success. “I felt like I was going in to my classroom every day and just failing my students,” he says.

Eventually, Rogoff connected with an algebra teacher in New York City, who became his long-distance mentor and elevated his teaching, skills that he took with him to a one-year stint at a D.C. charter school. Still, despite that city’s professional development seminars, he found himself again facing the same essential issue: “I was plateauing as a teacher.”

In 2015, that frustration, felt by thousands of teachers across the country every school year, propelled Rogoff and Vicky Kinzig—a Lower Merion high school friend who is also a former teacher—to launch KickUp, a tech startup that helps districts measure how effective their teacher training programs are. (Rogoff and Kinzig joined up with their third co-founder Eric Krupski about a year into their partnership.) With that information, districts and schools can create better professional development tools, which in turn can create better teachers, which—the ultimate goal—could mean better students. KickUp now has 60 clients with about 20,000 teachers in several states (though not yet in Philly).

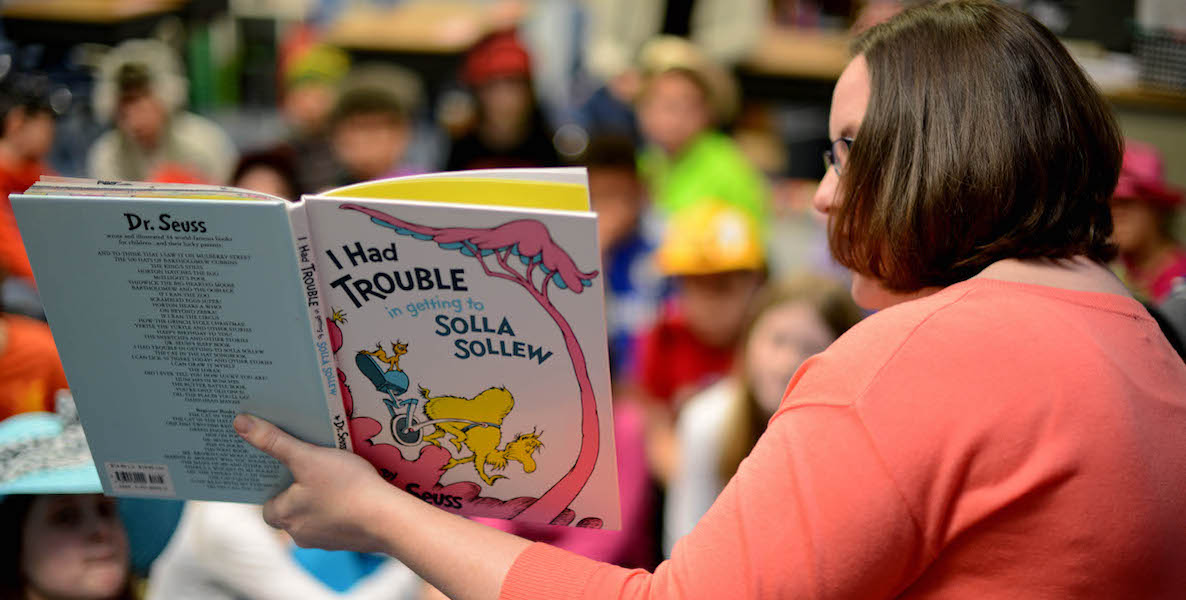

The need for this is clear. Education schools have long been criticized for how poorly they prepare teachers for being in an actual classroom, from a 1986 study by a group of education deans to Pres. Obama’s former Education Secretary Arne Duncan. Meanwhile, veteran teachers in Philadelphia and elsewhere continuously complain about the poor state of district-run professional development; too often, these teachers who feel unsupported opt out of their careers or leave the classroom for other education jobs. That churn makes it harder for schools to implement changes to how students learn; and without a sense of what works and what doesn’t, isolated instances of success have been hard to replicate across systems.

KickUp is addressing this issue at a fortuitous time. Under the new federal education guidelines Every Student Succeeds Act, districts are now required to more strictly assess the success of their professional development programs, not only measuring how much training teachers get, but also how effective that is.

“It used to be about seat time at training,” Rogoff says. “Now, it’s about impact.” KickUp measures this impact at a granular level, through software that follows individual teachers from training to classroom to results. Using goals set up by each district, the program regularly surveys different stakeholders in a school—students, teachers, administrators, and parents—to hone in on what kind of training has helped teachers better do their jobs; which teachers need additional help and which ones can be tapped as mentors; how the professional development has impacted parents and students; what the district needs to focus on in order to achieve their aims. ![]()

Each KickUp client—usually the head of professional development in a district or region—also has a service rep to help create the surveys, interpret the data, suggest ways to increase the response rate, and the like. (At least for now, Rogoff says, the company does not sell the software outright; the consulting is part of the package).

They also help guide clients on the five-point assessment path KickUp derived from Thomas Guskey, an education psychologist at University of Kentucky known for his work on teacher training and student assessment: teacher perception (did the teacher learn something?); teacher learning (as checked by a test); organization support (did the school support you?); teacher application (what happened when you put it into practice?); and student learning outcome.

This allows for a real-time picture of teacher development so that districts and schools can address successes and failings early and often, rather than waiting for the end of a five-year strategic plan, for instance, to know whether they’ve achieved their goals. The end game, of course—arguably the only thing that really matters—is student achievement. It is too soon to know how dramatically KickUp will help districts raise test scores, or graduation rates, or other markers of good learning. But in the districts where the company has worked longest, longitudinal surveys show an uptick in teacher confidence and learning, and already some impact on student experience, particularly in climate and culture (the easiest areas in which to make swift changes).

“We want to affect student agency,” Lauer says. “But first, we need to be sure teachers know how to use the tools effectively. Our homegrown surveys didn’t have the same sophistication to find teachers who were strong and those weren’t, and to identify the key questions that were going to help us avoid failure.”

One of KickUp’s earliest clients was the St. Vrain Valley School District outside Boulder, which hired the company to help it implement iPad learning across its 52 schools over the course of five years. In particular, St. Vrain Assistant Superintendent Diana Lauer says she wanted to be sure that 100 percent of teachers would be comfortable in the event of a technology failure—something that has tripped up other districts.

Using KickUp, she sends regular surveys to teachers asking them about this (and other) questions; she then uses the resulting data to pair struggling teachers with those who want to be mentors, and to deploy technology staff to classrooms with the most need. With KickUp’s help, even by the end of the first year, Lauer says, almost all teachers in their first group of iPad users said they felt comfortable with the technology—whether it worked or didn’t work.

“We want to affect student agency,” Lauer says. “But first, we need to be sure teachers know how to use the tools effectively. Our homegrown surveys didn’t have the same sophistication to find teachers who were strong and those weren’t, and to identify the key questions that were going to help us avoid failure.” KickUp clients pay anywhere from a few thousand dollars to tens of thousands of dollars a month, depending on the level of service they need. The company also has received over $2 million in seed funding from ed tech investors Reach Capital in California and Red House Ed in New York City.

Success, though, was not without its stumbles. When Rogoff and Kinzig first started working together, informally at first, KickUp was designed to be a peer-to-peer video mentoring program, matching teachers in need of guidance with those able to give it—like Rogoff with his long-distance mentor. The platform launched in September 2015…and virtually no one showed up.

It is too soon to know how dramatically KickUp will help districts raise test scores, or graduation rates, or other markers of good learning. But in the districts where the company has worked longest, longitudinal surveys show an uptick in teacher confidence and learning, and already some impact on student experience.

Luckily for the partners, the launch coincided with their participation in a California ed tech accelerator, ImagineK12, now part of Y Combinator. There, an entrepreneur mentor directed Rogoff to rethink how they were approaching the problem of teacher development: Is it urgent and important? Or just important but not urgent?

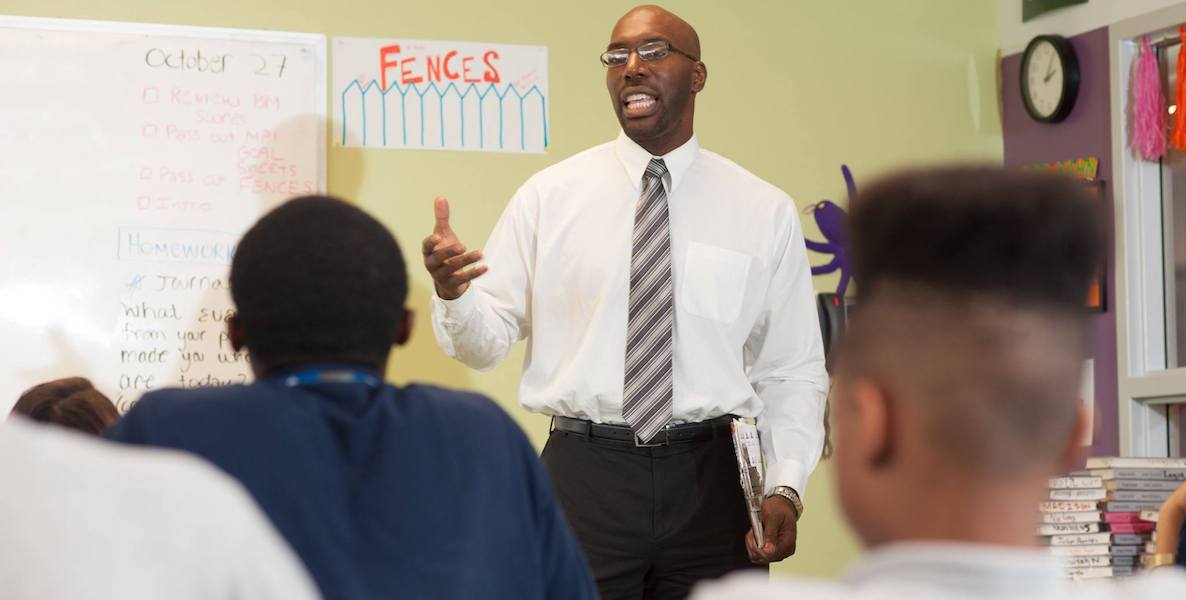

“We were solving an important problem,” Rogoff says. “But it wasn’t urgent for the teacher, who had all these other things to think about—making sure kids were doing their homework, communicating with parents, doing grades.” But there was one group for whom professional development was urgent: ![]() principals and district officials, who have a vested interest in teacher retention, and student advancement, and school improvement.

principals and district officials, who have a vested interest in teacher retention, and student advancement, and school improvement.

In one month that fall, Rogoff and his partners talked to over 100 administrators to find out what they needed to better teach their teachers, and honed in on one thing that came up repeatedly: Despite providing a lot of training, they had no way to track whether it worked, was being used, and made any difference.

By January 2016, KickUp had pivoted to its current iteration. They cold-called districts in states like California they thought might be open to their idea, and started working with those who called back—like St. Vrain, where an email introducing KickUp came across Lauer’s desk at just the right time. It didn’t take long for word to spread. The company’s biggest client is a region in Texas covering several school districts with about 1 million students; one district in Missouri recommended KickUp to several others, and the company now works around the state.

One district the Philly-based company does not yet work with is Philly, in part because to get off the ground, the startup needed the ability to work swiftly, so it first looked to smaller and nimbler districts with one main professional development contact. Rogoff says they have not yet approached their home district, but hope to in the near future—he’s pretty sure there’s a need.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated where Rogoff was first a teacher. It is Arkansas.