In the 10 months or so that Max Tuttleman, the 28-year-old philanthrocapitalist, has been trying to prevent opioid deaths, the problem has gotten worse, not better. It is, Tuttleman says, just as he predicted: “I’ve been telling everyone the numbers are going to increase, despite all our efforts right now,” he says. “We need a lot more resources on this.”

Indeed, last year was the worst year of the crisis yet, with more than three times as many Philadelphians dying from opioid overdose — usually heroin — than from gunshots. One particularly grisly stretch in December saw 35 people dead from an overdose in just five days; that doesn’t even take into account those who might have survived. In mid-November, the city’s health department announced that 40 people in one day were seen in hospital emergency rooms for nonfatal overdoses; and that doesn’t count those who declined to go to the ER for help after they survived.

It’s a tragedy that’s been growing nationwide for years, since opiates became a popular and easily-prescribed medicine for pain. But even as doctors and pharmacists have cut back on how often they prescribe drugs like Oxycontin, the use of heroin — a cheaper street version of the pharmaceuticals — has skyrocketed. Now, accidental opiate overdoses have overtaken car crashes as the leading cause of death in the United States. And Pennsylvania is particularly hit hard. In 2015, it was ninth deadliest state for heroin users. And as Tuttleman points out, “Philadelphia is where people in Pennsylvania are dying.”

The city’s Health Commissioner noted early this year that he expects to find a tally of over 900 overdose deaths in Philadelphia in 2016, reflecting a spike that began in 2011. (The official report will be out in April.) Many of those deaths involved not just heroin, but also fetanyl, a synthetic opiate that is purer — and stronger — than even the pure (purest in the country, some say) heroin available on the streets here. The center of the epidemic is, and has been, Kensington. But it truly reaches into every neighborhood. The U.S. Attorney in Harrisburg publicly revealed this year that he lost his son to an overdose 10 years ago. And in Philadelphia, Cozen O’Connor vice-chairman Tad Decker suffered the death last January of his son John, who struggled with a heroin addiction brought about by a reliance on painkillers for a sports injury.

“Everyone’s going to have to grab a shovel and dig in if we want to save our city,” Tuttleman says. “We’ve got to stop Philadelphians from dying.”

It was Decker’s story that first struck Tuttleman, when he read an op-ed by former Governor Ed Rendell in The Inquirer last year. Tuttleman, who watched five uncles struggle with addiction, felt moved to do something.

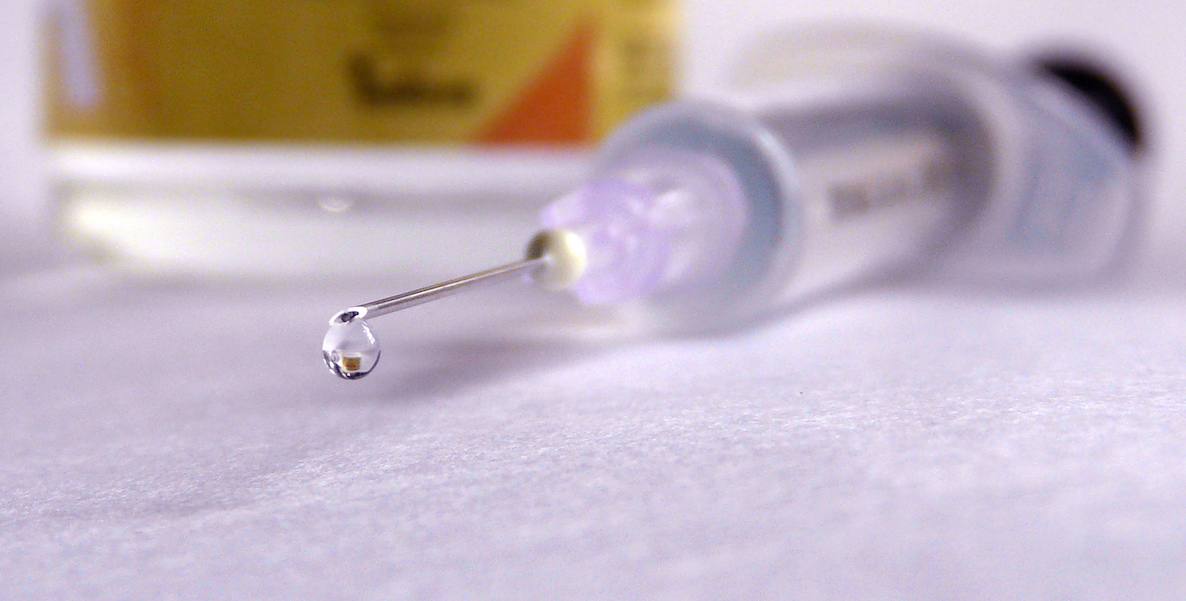

He started with what seemed like a simple enough idea: Use the Tuttleman Foundation to get the lifesaving drug naloxone into the hands of every first responder, every social service agency, every one who might encounter an overdosing addict. (Naloxone, known more commonly as Narcan, reverses the effects of heroin and is responsible for many of the overdose survivals here and elsewhere.)

He discovered that in Philadelphia, there is already funding for first responders, all of whom now carry naloxone with them. (Though often, it goes unused.) Eventually, he found Prevention Point, an organization that offers needle exchanges and other programs to keep addicts safe. The Foundation now helps supply naloxone to Prevention Point, and Tuttleman says he is also trying to negotiate a way to get nearly expired, unused naloxone from the police department to the organization before it spoils.

But Tuttleman — as with anyone who goes down this path — soon realized naloxone wasn’t the answer. “I thought it was a solution that hadn’t been recognized yet, that if you could stop people from dying, we could take hold of this problem at hand,” says Tuttleman. “But I was very wrong. There are 50 solutions that have to be all done together.”

To his credit, Tuttleman — who is not a public official, or a medical or law enforcement expert — has taken it upon himself to learn what those solutions might be. He now spends about a quarter of his time on “fact-finding,” going, for example, on police ride-alongs in Kensington to wrap his head around the “economic ecosystem” that fuels the heroin business. (The rest of his time is spent developing his portfolio for Gabriel Investments, business in Las Vegas, and his other charities.)

It’s a typical response to a passion project for Tuttleman, whether it’s a play that moves him at Fringe, or a small literacy program in North Philadelphia. He dives down deep, and emerges with wonder and skepticism and enthusiasm. This issue, personal and deadly, is the most critical he’s taken on since becoming involved in his family’s foundation, which also supports Recycled Artists in Residence, Fringe Festival and Tree House Books.

The power of his foundation’s money may get Tuttleman in the door, but it’s his ebullience and curiosity that gets things done. His real skill, he says, is the ability to bring people together to talk about an issue, and to “lobby” for social causes — such as helping to ensure the state’s Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs included $200,000 for naloxone for Philly officers in its latest budget. So far, Tuttleman says his foundation has invested around $75,000 into reducing heroin overdoses in Philadelphia, out of an expected $150,000.

Still, it’s early days in curbing this epidemic. Pennsylvania has joined 37 states in launching a Prescription Drug Monitoring Program, which gives pharmacists and doctors access to patients’ prescription history, to track possible addiction. The Mayor launched a multifaceted task force late last year to address the issue (though it, too, is still mostly in fact-finding phase). And — particularly exciting to Tuttleman — the state’s new medical marijuana law also includes “severe or intractable pain” as one of 17 medical conditions that will qualify for a cannabis prescription.

Get More From Every Story

We include boxes in nearly every story to help you take action. Click the boxes below to see how you can make Philly better.

Will these keep enough people alive, soon enough? It’s a question that plagues Tuttleman — as it should plague all of us. That’s why he’s working so hard to evangelize about the need for more, more, more — research, resources, outreach. He flips between gratification that so many are talking about this, and frustration at the slow pace of results. A few months ago, in a moment of great irony for Tuttleman — who failed to graduate from Temple, among other universities — Temple Contemporary invited him to speak to students about the heroin epidemic along with Svante Myrick, Ithaca’s dynamic mayor who is tackling his city’s opiate crisis by opening a “supervised injection facility” near a city park. It’s the sort of exciting (and controversial) idea that could be a game-changer in Philadelphia, too. But it’s also the kind of idea that can stop all conversation in a city as large and varied as Philadelphia.

So, it’s back to slow, steady work for Tuttleman, who says he’s just getting started. “Everyone’s going to have to grab a shovel and dig in if we want to save our city,” he says. “We’ve got to stop Philadelphians from dying.”

Header photo by Andres Rodriguez via Flickr