“Hope is a thing with feathers, that perches in the soul … ” Emily Dickinson

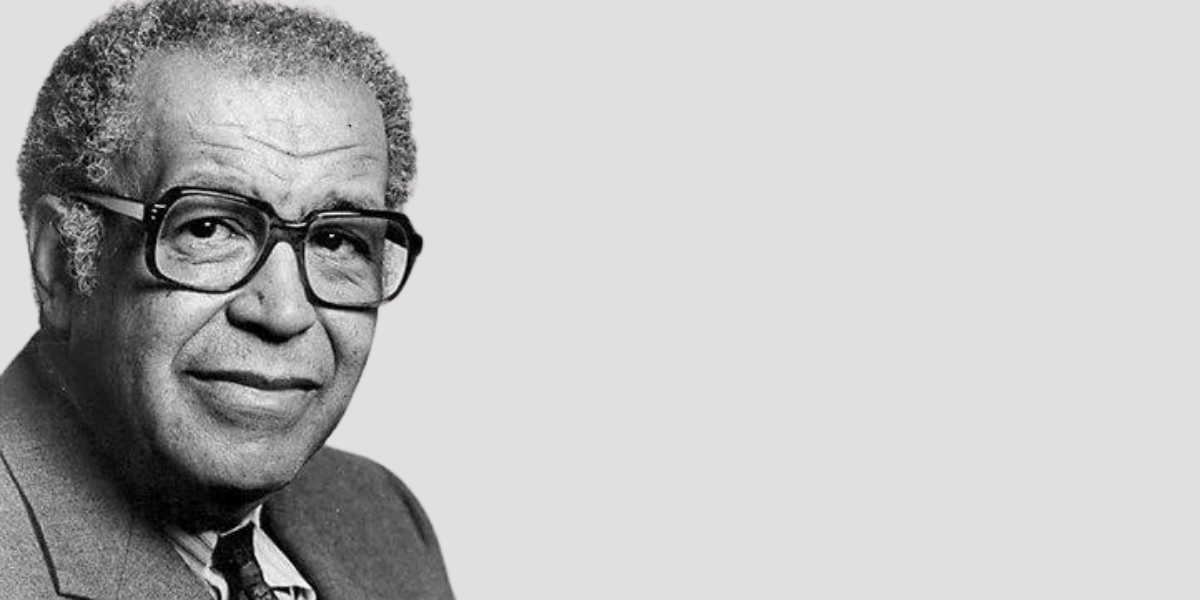

Judge A. Leon Higginbotham believed in the power of deep research. He believed in precise articulation of the argument; the categories, the words and the etymology of the words.

He had won highest honors at Yale University. He was a born scholar and born litigator who worked hard at honing the craft. When he crossed the bridge from his native Trenton, New Jersey into Philadelphia, the Athens of the new world, and was rejected by the prestigious law firms there, he hung his Yale Law degree in the “colored” part of town.

I remember that, once upon a time, we were “colored.” Other than purely descriptive of melanin in the skin, this designation had social, economic, political, and constitutional implications; soul crushing implications; soul obliterating implications.

“I’ve never seen a colored fireman In Trenton,” Higginbotham’s factory worker father warned him. His father was trying to nip in the bud Leon’s juvenile aspirations that would surely bring disappointment. But his mother, a domestic worker, overheard her husband’s advice and quietly enrolled their only son in a Latin class, a required course for college admission — and a course not available at her son’s public school.

At the age of 16, Leon applied to Purdue University College of Engineering and was accepted. The problem was, the only housing offered to “colored” students, in West Lafayette, Indiana, in the winter was an unheated attic room. These conditions were tough and inhumane, so Leon went to the university president, for a face-to-face meeting, begging for relief for himself and the 11 other ”colored” students, living with him barracks-style.

It was a modest request; a respectful plea from a teenage boy. None of the other “colored” students were with him. There was no demonstration, no request to desegregate the heated student dorms for the 5,000 white students; merely asking for a segregated corner for the 12 “colored” students. Just a crumb; just some show of dignity from one human being to another. Instead the university president said, “Higginbotham, the law doesn’t require us to let colored students in the dorm, and you either accept things as they are or leave the University immediately.”

Leon left Purdue, changed his major from engineering to law, and applied to a different university, but he refused to “accept things as they were.” When he won every honor in Yale Law School’s history for advocacy, he wasn’t surprised when offers of interviews, from prestigious New York law firms, were made to every student finalist in the competition, except him. Neither was he surprised when he crossed the Delaware River to Philadelphia, to less than thunderous applause from the Pennsylvania Bar.

He knew he had a fight on his hands: not for a day, or year, but for his entire life. When Leon Higginbotham died in 1998 he left a string of accomplishments that would be the envy of most of us in the law or as human beings.

He didn’t conquer racism. He didn’t save Metropolis like Batman, but he did change the world to the benefit of us all, our children, and our children’s children. He left the world a whole lot better than he found it.

Edward S. G. Dennis, Jr. served as a law clerk to Judge Higginbotham. Dennis received a Presidential appointment to the position of U.S. Attorney in Philadelphia and went on to be appointed Assistant U.S. Attorney General, Criminal Division and to serve as acting U.S. Attorney General. He retired from the law as a partner at the law firm of Morgan, Lewis & Bockius.

![]() MORE ON A. LEON HIGGINBOTHAM JR. FROM THE CITIZEN

MORE ON A. LEON HIGGINBOTHAM JR. FROM THE CITIZEN