As I pedaled around Saturday’s massive protest, on the edges, behind, beside, I stopped to send photos to my daughters in Vermont and Chicago. News from the ancestral homeland, the old country. Your streets. We’re passing your pediatrician’s office now. See?

Sometimes, when the group called the names of the most recently murdered, I’d pull over on my old green bike—a Sunday School boy once called its predecessor “the bus”—and cry and pray: for the murdered, the protesters, the organizers, all of them aged from my stepson to youngest daughter.

Then I’d ride on, sometimes behind the phalanx of police on bicycles, or on the sidewalk next to the street full of young people, more of them white than I’ve seen since I was five. These are some of my earliest memories of television, along with scenes of war from Vietnam, and of assassinations: young white Americans loading onto buses, heads hanging out the windows for the Freedom Rides.

I remember my community’s disbelief that white youth would choose to share in the state contempt for black life, and the U.S. appetite, as I understood it after the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, for black death. I grew up on those images.

I grew up on the galling assumption that we had to die in great numbers, including children, and beyond that, we were required to perform that death on television and in photos, before white America would notice that our death made their lives possible. I grew up to accept that white America could not see the preciousness of black life and the divine spark glowing from within us. America could-not-would-not see amazing black survival-lives unless somebody white came along to die with us.

One of the family text responses to my messages on Saturday was that I was there to protect the protesters! We were joking, but there were many of us masked Godmothers that day, handing out water, nodding to one another, watching from a distance, with love and pride and fear for their lives.

Mainline churches ask where are the young people? Here they are. They’ve come of age under a black president. They understand the urgent, existential threat climate change makes to life itself. And that black life is life, all life. I pray for them to hold onto this body memory, learned after ritual walking together, sharing breath and risking safety. This has been their global, distanced dance. Call it mass life: the refusal to sanction death in their name.

At 3:30pm, I turn off Broad at Wharton and ride north on 13th to Pine, where, as the interim rector at St. Luke & the Epiphany, my husband, Bob Smith, is performing a wedding. It will be only the couple, a handful of loved ones, and a photographer outside on the wide, white-pillared portico, fragrant with flowering Linden trees. I get there early and likely startle one of the grooms by riding up too fast behind him to catch the church gate.

But the helicopters circle and drone overhead and the tiny wedding party opts to go inside. I wait across the street with neighbors for a glimpse of them coming out, maybe a glimpse of Bob, who will be joyous, I know, to perform his first service that will not have to be videotaped and streamed to this new, wonderful parish.

Then it happens. The people I’ve ridden alongside are coming up 13th Street! Who could not recognize the man with no shirt pushing the pregnant woman in a shopping cart, the person with the spray of cyan hair, the Jews against Racism sign, the voices of leaders still chanting names through their masks: a memorial in breath and body and sound.

Just married, the couple comes out onto the portico, two men in suits, matching black masks next to the white pillar, and then the others, spread out on wide church steps one full story higher than the street. They nod toward the marchers. For a moment chanting stops. I hear whispers and feet on the asphalt. Helicopters, still. Then, the marchers turn their faces toward the newlyweds and together they make the sound of one dear, happy chorus: “Awwwww!”

The wedding party claps, and I see my husband’s head peek out the red doors. As Deuteronomy tells us: Choose life.

Lorene Cary is a lecturer at Penn and author, most recently of Ladysitting: My Year with Nana at the End of Her Century, a caretaking memoir, and My General Tubman, a play about the complex journey of the abolitionist/activist that ran this year at The Arden Theatre.

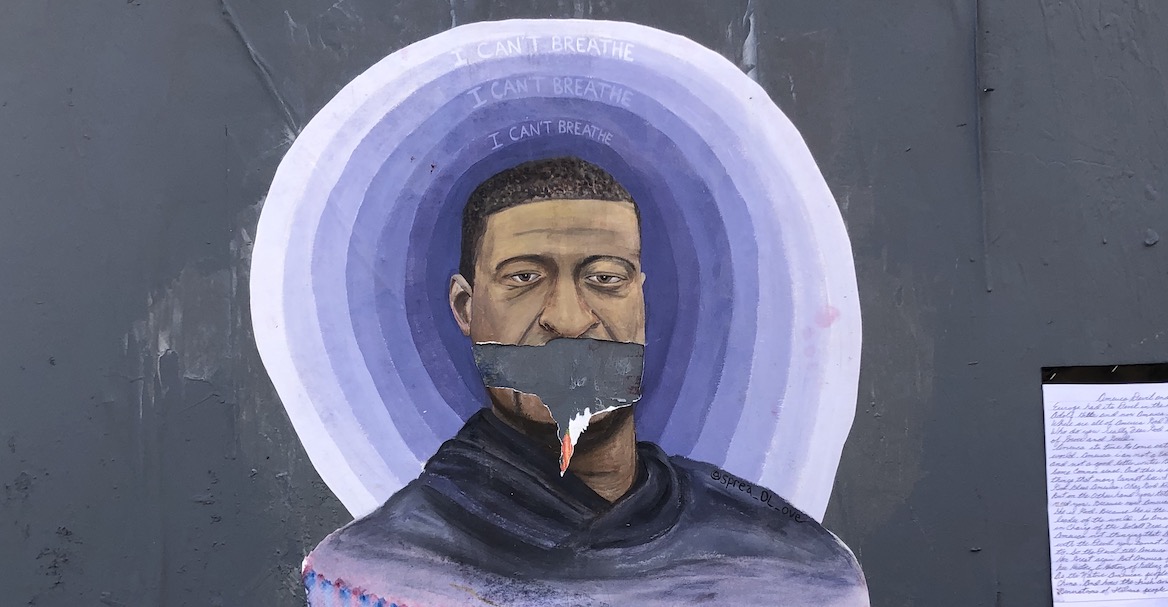

Header photo by K.C. Tinari