In 2000, when Evie McNiff brought Children’s Scholarship Fund to Philadelphia, she was new to philanthropy, and to public education in the city. A former environmental consultant whose youngest child had just started kindergarten at Springside Chestnut Hill, she wanted to get involved. So she visited schools in the district—public, private and what few charters there were at the time. She was struck by the work of private schools that were educating low-income children whose parents felt they couldn’t get a good education at their local public school. That was the impetus behind CSF Philadelphia, which has awarded more than 22,500 scholarships to Philly families to help cover tuition costs at local private schools.

Seventeen years later, McNiff is an education advocate with a hand in many of the city’s most pertinent, and sometimes controversial, school conversations. She is a founding member of the Philadelphia School Partnership, and of its advocacy arm, Philadelphia School Advocacy Partners. As she prepares to step down as CSF board chair, and to join the board of the Philadelphia Foundation, I caught up with her to talk about the state of giving in Philadelphia.

Roxanne Patel Shepelavy: We keep hearing that the philanthropic landscape in Philadelphia is diminished, with the loss of local grants from Pew and the Annenberg Foundation. And we recently ran a piece that pointed out that Philly is in the lowest 20 percent of personal philanthropy among the top 50 metropolitan areas in the country. What do you make of that?

Evie McNiff: From my vantage point, I see it differently, based on what I see getting funded. When I started doing this, the people I was talking to had no comfort level or knowledge of where to invest in education. It wasn’t that they weren’t interested; they didn’t know where to put their dollars. This was 2000.

What I see now, 17 years later, is every school that’s doing a good job educating kids across all sectors—whether public, private or charter—has a [strong] board. I was begging people to get on our board for many years. Now there’s a tremendous interest in the business community to get younger people on the boards of these schools. They are looking for ways to advocate around public education, and finding ways for failing schools to be better. There are parent groups getting together around the worst schools in the District, talking about quality, and bringing in partners and money. So philanthropy in the education sector has escalated tremendously.

RPS: What’s missing?

EM: In terms of accelerating impact, the missing link in Philly is collaboration. I know that everybody has too much on their plate. But in other cities, there’s much more of that. That’s what business leaders understand in Pittsburgh: There has to be collaboration with the nonprofit sector. They meet monthly to identify the areas they need to get behind, with their Chamber of Commerce. Or Boston–there, the business community sanctions stuff and the money flows.

But not here. In the business community writ large, there are a lot of leaders who want to do this; it’s just there hasn’t been a coordinated effort. So we need to figure out a key partner that can take this on and engage business leaders to do that. Companies don’t want to do due diligence—they don’t have the time or the attention, or passion. They just want to know where to invest, that they’re not going to be embarrassed, and that it’s having impact, that’s all. That’s what I have come to realize: There are organizations that support Children’s Scholarship Fund that have no idea whether we support charters, high school, college—they just know that this is an accredited organization that’s doing good things.

RPS: You’re one of the founders of PSP, a school reform organization that has become controversial, because for many it represents the charter school movement—one side of an issue that people take sides on.

EM: I understand that. It’s disheartening and it’s not productive. If we’re really talking about getting stuff done, we can’t have that. Everybody has to learn to be more collaborative. Everybody came into PSP with pure motives, regardless of their politics. The whole purpose was to help the District make better educational options available for Philadelphia children as quickly as possible. PSP has invested over $15 million to improve District schools and another $1.2 million to fund better principals in the District. Who else in Philadelphia is funding District schools at that level? No one, other than, perhaps, the William Penn Foundation.

“In terms of accelerating impact, the missing link in Philly is collaboration. In other cities, there’s much more of that. That’s what business leaders understand in Pittsburgh: There has to be collaboration with the nonprofit sector. They meet monthly to identify the areas they need to get behind, with their Chamber of Commerce. Or Boston–there, the business community sanctions stuff and the money flows. But not here.”

RPS: What happens when you try to explain that to people?

EM: People who I’m trying to get engaged in the space, the business community, really don’t have the bandwidth to understand the complexity. They don’t always know the difference between a charter and a District and a private school. They don’t understand how things are funded, or the School Reform Commission. It is not out of bad will. Few have the time or desire to get deep into the weeds of school improvement. We need to talk to people who are within the system to figure out better ways to do things, and not necessarily try to have this broader fight.

There are things that I don’t think many people can argue about. I heard [Citizen contributor and Mastery Shoemaker Principal] Sharif El-Mekki say something the other day: “Nobody in America is anti-school choice. It’s just that some people only want choices for themselves or aren’t aware that they’re using choice.”

I know when Sharif uses the word “choice” it makes everybody bristle. But you know, Masterman is a choice. I hate the word choice; I hate the word voucher; I hate the politics of school improvement. The point is, if we focus on quality and the ability of families to access quality, they don’t care if it’s a public, private or charter school. They just want a good school for their children. We have a responsibility to make sure that the kids who are stuck in failing schools get access to good schools. Period.

RPS: I talked recently to a businessman who said to me that a lot of business people don’t want to give money to the School District because they don’t know where it will go, but if there was a list of what the District needed, a lot of them would step up. Is it your impression that businesses need that?

EM: Yes, but businesses have to take a more comprehensive approach. It’s not enough to have a employees take the day off from work to do community service. You’ve got to do more than just paint the walls. I think there are really successful ways to raise money around some things, but it can’t be an either or—it has to be an AND. If I was a CEO I’d like to encourage my employees to do more than just a community service day, to actually get on a board and help solve problems and use their skills.

RPS: How do you get people not already interested in education to be interested?

EM: There’s a population growth of really great people who want to live in the city now. They’re not going to stay if we don’t take care of the schools. That is a wakeup call to the Chamber and all these business people. We need to harness this new energy in Philadelphia and find ways to help them make an impact and change educational outcomes for city kids. People want to support a student who’s succeeding. We all know that these kids can succeed; we just need them in schools that will allow them to succeed.

In a perfect world, you would have the District be an authorizer for every school in the city. Several years ago, [the SRC] did a facilities study, saw where schools were located. PSP looked at the map and said, Where are the holes? Let’s try to get quality operators in there, and turn them into District schools. So then the District would have a quality school in each neighborhood.

There has to be more strategic thinking and support. I believe Dr. Hite wants to do everything right for kids, wants to be successful, wants parents to not be yelling at him at SRC meetings. But he also needs support and help in order to make the difficult decision to close chronically failing schools and turn them over to a better operator. If you have a basket of schools that are not succeeding, you have to help move them forward.

RPS: Well, it seems like this went off the rails because there was no authorizing agency closing charter schools that weren’t doing well, either. People can say that charters aren’t doing better than District schools because in fact, a lot of them aren’t. That whole conversation could have been prevented if we’d let them be shut down.

EM: Yes. You have to close the failing charter schools. That’s essential. You have to close a bad private school—a bad private school isn’t going to continue because parents aren’t going to send their kids there. My interest is to take the politics out. But I understand that there’s a political side to it.

“I believe Dr. Hite wants to do everything right for kids, wants to be successful, wants parents to not be yelling at him at SRC meetings. But he also needs support and help in order to make the difficult decision to close chronically failing schools and turn them over to a better operator. If you have a basket of schools that are not succeeding, you have to help move them forward.”

RPS: How would you do that?

EM: [Laughs.] I’d let the mothers run the world. I know that’s naive and silly, and I don’t pretend to think that. I just think women are more willing to collaborate, and willing to find solutions that are not simple and straightforward.

RPS: If there were more women-led businesses here, do you think there would be more investment in schools?

EM: Yes. Women understand schools, they’re all over the schools—teachers and principals. It’s a very tough job and you’re never off, and you’re always on call. It’s brutal. But people feel it’s a calling, and that’s what I feel every time I go into a school. Even in some of the terrible District schools, they feel like it’s a calling; they’re doing the best they can with what they have and what they’ve been trained to do. You look at every school, even the well-resourced school. There’s an army of people who are volunteering. And they’re mostly women.

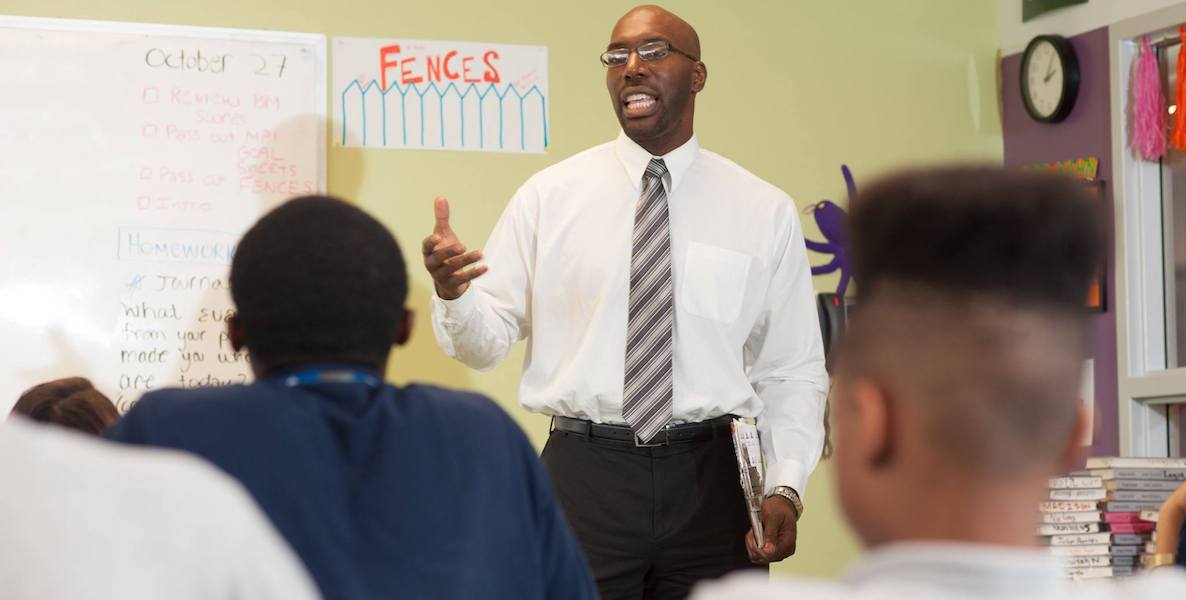

Header Photo: Fels Institute of Government