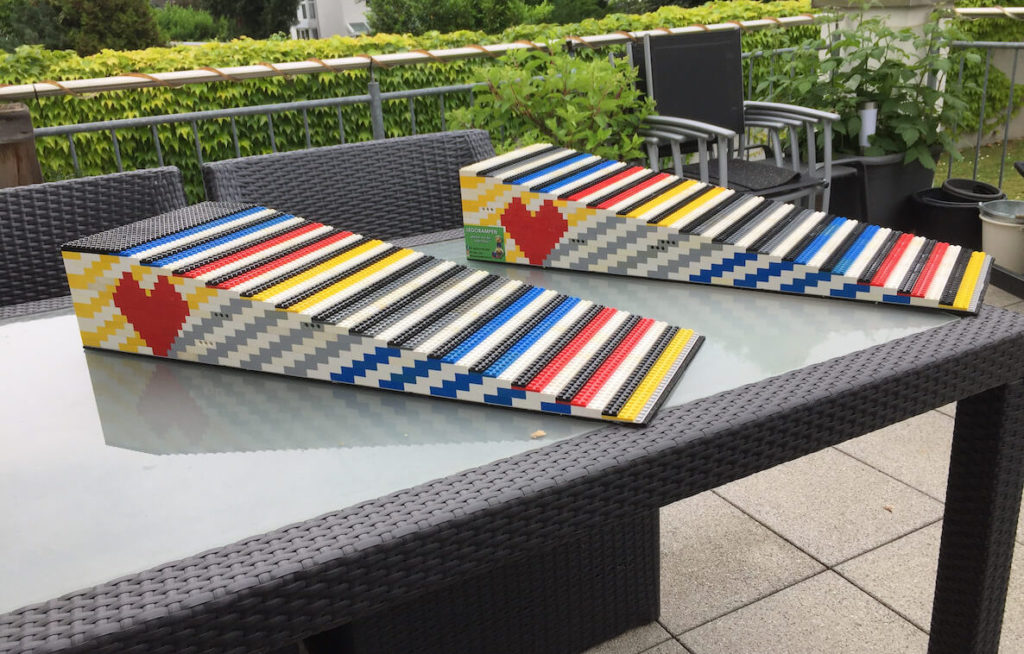

Rita Ebel proudly shows off her latest creation in front of the Zoom camera: a wheelchair ramp featuring a pink pony made of LEGOs on a grey LEGO background.

“This is for a severely handicapped 12-year-old girl in Austria,” Ebel says. “She is very much into horse therapy, so we chose this design for her wheelchair ramp that will help her get over a small step from her parents’ house to the terrace.”

Ever since Ebel read in a disability magazine a year and a half ago that wheelchair ramps could be built out of ordinary LEGOs, she has embraced the idea so enthusiastically that she is now internationally known by her Instagram moniker: “The LEGO Granny.”

“My 13-year-old granddaughter mock-complained that all her visits revolve around LEGOs, so my daughter quipped, ‘Well, you have a LEGO granny,’ and the name stuck,” Ebel says.

The 62-year-old retiree has been in a wheelchair since a car accident injured her spinal cord 26 years ago. So she understands intimately the frustration with trying to get where she needs to be in her hometown of Hanau, Germany, which—like Philadelphia—has many older buildings with steps leading up to their entrances.

Ebel aims to make Hanau barrier-free, one LEGO at a time. She and her family have built dozens of ramps from donated LEGOs for shops and private homes, and have inspired hundreds of people around the world to copy the idea. “We have used more than 1.2 tons of LEGO pieces,” her husband, Wolfgang Ebel, chimes in.

MORE SOLUTIONS FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES

“Able-bodied people might not even notice these barriers, but for many people with wheelchairs, strollers or walkers, they present insurmountable obstacles,” Rita Ebel knows. “The colorful ramps are a creative, joyful way to direct attention to this issue, and they also send a signal to the disabled: You’re welcome here. It is just as important to overcome the barriers in the minds as the barriers on the streets.”

Philly could use some LEGO ingenuity

In Philadelphia last fall, the Mayor’s Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion released a draft plan for its work that included an alarming statistic: Of 537 public buildings assessed, only 55 had no accessibility issues for people in wheelchairs. Of the other nearly 500, some do have wheelchair ramps, but all have barriers of some kind that prevent residents with disabilities from fully taking part in services at libraries, parks and other government buildings.

The City’s plan calls for moving activities in the short term, and eventually renovating the buildings—but ensuring every public facility is fully accessible will take years, and it will be expensive.

Imagine, instead, a recreation center in South Philadelphia sponsoring a LEGO ramp building project with local children during the summer, using LEGOs donated from neighbors’ homes. It would keep the plastic blocks out of the landfill, provide a fun and educational activity for the kids, and be a brightly-colored way to welcome park-goers who are in wheelchairs.

Meanwhile, private buildings like stores and rowhomes in Philly—almost always accessed by a stoop—are also difficult to maneuver for people in wheelchairs. Industrial ramps cost upwards of several hundred dollars and thus can be prohibitively expensive for shop owners and families. A bag of 10,000 used LEGOs on eBay, though, runs about $172.

A small but growing movement

The Ebels give away their ramps for free, often dropping them off themselves if the location is within driving distance. Otherwise, recipients cover the relatively low shipping costs. (The ramp from their home in Germany to Vienna cost only 25 euros.) Her ramps have been placed in front of shops and homes all over Germany, but also traveled as far as Paris and Vienna.

Ebel won’t take monetary donations, but does sometimes direct people to LEGO’s “swap and sales” platform, where she often gets her bricks. Originally, she put out calls for LEGO donations to build ramps for her hometown, but after word got out she started receiving LEGOs from all over the world almost daily. “A lot of people have them in their attic and are happy to donate them to a good cause,” she notes.

Ebel has started a small but growing movement. Her husband wrote extensive instructions, volunteers translated them into nine languages, and the Ebels have sent nearly 500 construction plans around the world for people who want to build their own ramps.

“Anybody can copy the idea. But most people underestimate how many LEGO blocks you need,” Rita Ebel says. “Every piece needs to be glued, so the ramp is stable enough for the heavier electric wheelchairs.” Depending on the size of the ramp, she needs 7,000 to 8,000 LEGO pieces. “People think LEGOs are lightweight but the ramps easily weigh up to 30 pounds.”

LEGO ramps had success in Texas

Rachelle Khalaf, a media advisor in Houston, Texas, was one of the first to bring Ebel’s idea to the United States last year. When she saw a YouTube video about the LEGO granny, she immediately thought this could be a great “summer pandemic project” for her LEGO-obsessed kids to help their father who was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis in 2018.

Sure enough, “they went bananas,” Khalaf said with a laugh on ABC13. “We have a small step in front of our house,” and the kids went to work to build a LEGO ramp for their dad. They soon realized the LEGOs in the kids’ toy box wouldn’t be enough for a sturdy ramp and asked online for LEGO donations. “It’s a lot of sore thumbs,” Khalaf says—but worth it. “They are excited to say they built this for their dad.”

Their neighbor’s daughter occasionally needs to use a wheelchair, too, and asked if they could build one for her as well; other families have reached out to ask for advice, and so the movement grows organically.

For the Ebels, the LEGO ramps have become a near full-time family affair. “Our house looks like a LEGO warehouse!” Wolfgang Ebel complains in mock outrage. Their daughter and granddaughter, as well as friends, help build the ramps. “It takes about 10 hours for the simpler ramps but 20 to 30 hours if we build a design pattern like the horse.”

One big drawback to bringing LEGO ramps to Philly

There is one drawback to bringing an Ebel ramp to Philadelphia: They don’t comply with official Americans with Disabilities Act’s (or the German equivalent for that matter) stringent ramp requirements around angle of slope, materials and handrails. This speaks to one reason there are not ramps already in many older buildings like those here and in Germany.

“For us wheelchair users, the LEGO ramps are ideal, but they do not have the slope and handrails required by the ADA,” Rita Ebel says. “What the bureaucrats don’t understand is that in the old buildings, it is often impossible or impractical to build a 10-feet-long ramp.”

She has heard of city officials, for instance, in Munich, Germany, who forced shop owners to remove the ramps, and she considers herself lucky that the mayor in her hometown supported the idea from the beginning. “All our ramps are still there.”

The shop owners in less tolerant cities have found ways to work around the ordinances by not installing the ramps permanently but laying them out when needed. “Just look around your town. When you see how impossibly placed some of the official ramps are and how often there are no ramps at all, it raises your heckles. We wheelchair users could care less whether the slope ratio is 1:12 or 1:10 if a ramp allows us to get into a building safely,” Ebel says resolutely. “If we were to ask for an official permit, it would be denied. So we don’t ask and just build.”

Nobody has ever been injured by using one of her LEGO ramps, Ebel assures her fans. “On the contrary, they are safer because the LEGOs provide more grip than the aluminum models, and people love them,” she says. “Young people lie down right next to them to take a selfie, and the younger kids often try to pry off a colorful piece.”

Of course, they don’t stand a chance. Ebel makes sure to glue every piece securely.