Karenina Angleró arrived in Philadelphia two days after María. She had booked a flight long before the storm to visit her best friend, who had come to the city to study and settled here after falling in love. And Karenina needed some time away from Puerto Rico.

A week before Hurricane Irma hit the island in early September, Karenina had been laid off from her job as a waitress in San Juan. Shortly after that, she was sexually assaulted walking home one night. She reported it immediately after, only to be criticized for her own behavior by the female police officer who responded.

And then María pummeled through the island overnight, rendering Puerto Rico a perpetual scene of catastrophe and chaos. Her home was safe and sound, but not unscathed. The front entrance was blocked by plant matter, trash, and fragments of roofs. A mango tree 30 feet tall had split in half and fallen on the colonial style house.

As she made her way through the throngs of people desperate for a way out at San Juan’s airport, Karenina realized she was lucky to be on one of the few flights not cancelled. She reasoned she could figure out what came next, for herself, her partner, and her island, after returning.

Karenina’s message to the city? “Que nunca falte la empatía.” May empathy never be lacking.

The first few days in Philadelphia were a respite. Karenina walked the city and visited museums. As a freelance illustrator, she was excited to immerse herself in Philadelphia’s arts and culture life, even if temporarily. However, guilt gnawed away at her core. Unlike her mother and partner, she could shower and cook every day with ease. Unlike her island, she had stable sources of electricity and water at her fingertips. Mayaguez, the western municipality where she is from, was constantly in the back of her mind.

Karenina hadn’t come with the intention of staying here. But then, she never left. Like many other hurricane evacuees who had originally planned short visits to Philadelphia, she was convinced by her friends to remain here. Even so, “the decision of telling my friend to cancel the return ticket was the most intense one I have ever taken in my life.”

During the first few days after a return home indefinitely postponed, Karenina experienced “severe depression.” She barely spoke and stayed in her room most of the time. Karenina had only come to the United States once before, when she was very little. She had left her her mother, her loved ones, her cats, her home. She broke up with her partner after a few weeks due to the distance: “We love each other a lot, but I’m here.” Maria had turned everything around in a sudden and fulminating turn.

To make matters worse, Karenina had heard nothing from her mother in Mayagüez during her first two weeks away. Her uncle needed dialysis. Via friends from school she had not seen in years, she relayed to her mother that she had left the island.

Coming to Philadelphia has often forced her to relive the trauma of Maria and of leaving. “I have to give Lyft and Uber drivers the Puerto Rico 101 every time I get in a car. Why is Puerto Rico an American colony? How does the government work? It’s like teaching class every single day.”

Yet, even with the challenges, Karenina recognizes and cherishes her safety net here. For now, she is staying with the friend she came to visit and their partner. They are both “very hands on,” and provided her with unconditional love and support. Between the three of them, they have lent each other the energy to survive the pain after the storm. “It was only a month ago that I began to find mental silence,” she says.

Karenina also recently began working at Camden nonprofit Hopeworks ‘N Camden, as a counselor for high risk youth, helping them achieve mental and physical wellbeing as well as academic and professional goals. “Helping others has helped keep me sane,” she says.

“Many on the island believe that those who left gave up, but there are different kinds of pain,” she says. “The diaspora is suffering here in profound sadness. But many who are part of it are fighting everyday and questioning the status-quo and mobilizing for us and Puerto Rico.”

In many ways, Karenina represents two sides of the same coin: She is both a victim and a survivor of María. While she is suffering the loss of the life she knew, she recognizes that being an evacuee with housing and a job places her in a unique position to help other Puerto Ricans who have been displaced by the storm.

Last month, when a group of Puerto Ricans that included university professors, artists, community organizers and social workers, invited her to organize a press conference in front of City Hall about the humanitarian crisis happening in Philly, Karenina jumped at the opportunity to support them. The action was successful: FEMA extended transitional housing agreements for those staying in hotels until March 20th, rather than evict them on February 14th.: “We are trying to help whomever, however,” she says “As a diaspora, we have a moral obligation to the island.”

More than anything, Karenina is perplexed by the city’s response, or lack thereof, to the situation. “When organizing, we couldn’t explain to ourselves how Philadelphia, supposedly a sanctuary city, could leave these evacuees on the streets,” she says.

Karenina left Puerto Rico without saying goodbye. She went back for closure in December, the first time she had been back since the storm. The experience was a “rollercoaster of emotions.” To her, Puerto Rico—which means “rich port”—describes itself with its own name. “Everything is rich..the flora, the fauna. Everything is abundant,” she says. “What does a tourist say when they visit our island? That it is beautiful, in more than one way. But that Puerto Rico has been erased. There is no description of Puerto Rico as it was before.”

Now that she’s back, she struggles every day with not knowing when she will see her mother, her former partner, her friends, and her island again. The image of the toldos azules, the blue roofs that FEMA set up temporarily to shield damaged houses from the elements, left an impression on her. She relishes the fact that although infrastructural recuperation has been slow, “nature is reclaiming everything.” At least in that sense, Puerto Rico is rising again.

Still, she feels like a visitor in her new city. Though she has a Philadelphia area code and ID, the move doesn’t feel real, even after five months. She is beginning to understand her place as a new member of the Puerto Rican diaspora. While she struggles with her own situation, Karenina is supporting her loved ones and helping her island. Their trauma and circumstances comes first.

![]()

During one of her first nights in Philadelphia, her then partner, still in Puerto Rico, called because a man was staring at her through the window and masturbating. Every time she called 911, she was told it wasn’t urgent because they were dealing with serious crimes all over the island. “How could that not be urgent?” Karenina asks. When she tried to call 911, it automatically forwarded the call to Philadelphia’s police. “I have never felt as helpless. All I could do was call her every half an hour to check in how she was doing, while she was hiding in the bathroom holding a knife.”

Like many other evacuees, her suffering is occurring in geographic dislocation. “Many on the island believe that those who left gave up, but there are different kinds of pain,” she says. “The diaspora is suffering here in profound sadness. But many who are part of it are fighting everyday and questioning the status-quo and mobilizing for us and Puerto Rico.”

![]() The restaurant where Karenina used to work never opened again. If she ever goes back, she wants to return with the guarantee that she can help the island. Right now, she believes she would only be another mouth to feed. She also fears what she will return to: “Puerto Rico is being erased. Same country, but with a different name. If I go back, it will not be the country that I knew.”

The restaurant where Karenina used to work never opened again. If she ever goes back, she wants to return with the guarantee that she can help the island. Right now, she believes she would only be another mouth to feed. She also fears what she will return to: “Puerto Rico is being erased. Same country, but with a different name. If I go back, it will not be the country that I knew.”

So she is staying, looking to use the resources she has here to help other evacuees. “They are Puerto Ricans, even if they aren’t in Puerto Rico,” she says. “In Puerto Rico, people don’t have anything. But what they do have is familiarity of their homes, their country…but evacuees here don’t even know the language.”

Karenina wants to convince Philadelphia to take responsibility for the situation and help care for the evacuees. She believes that to do that, though, it is important to convince the “Philadelphia native, the neighbor, the citizens of Philadelphia, not the people with money” that there is a humanitarian crisis in the city’s midst. That’s what she hopes was accomplished through the City Hall press conference. “If people didn’t know, now they do. And there is no excuse. They need to act.”

Her message to the city? “Que nunca falte la empatía.” May empathy never be lacking.

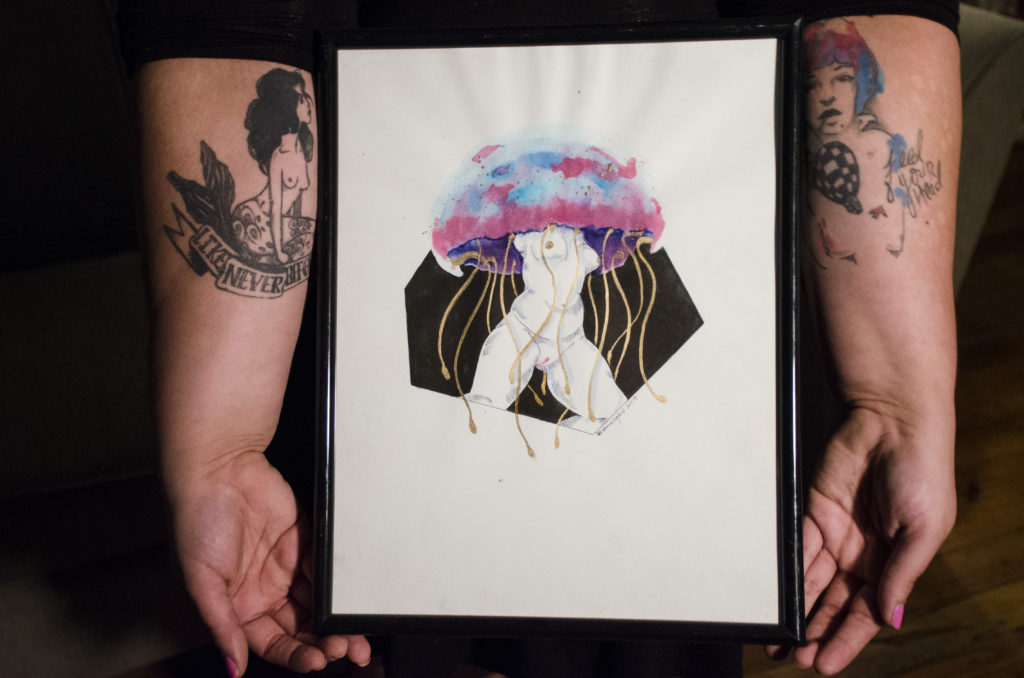

Photo by: Cameron Hart