I grew up in the desert. And, not just any desert—I lived and attended school in Qom, Iran, for several years of my childhood. My parents had always had friends from all over the African diaspora and the Muslim world, and wanted us to experience living abroad, an experience they thought would provide a powerful counter-narrative to the hegemony and “American exceptionalism” that we would undoubtedly be bombarded with as American citizens.

I was not an emigrant per se—we were expatriates—so I don’t intend to compare our circumstances with those of many refugees and immigrants. However, there were some similarities, and in school, I needed many of the same supports. Language acquisition, social capital, navigation of new culture, were all challenges, yet areas we were able to access tremendous support. My eighth grade year was phenomenal. Although I had to work very hard in literature and my text-dense courses like history and geography, I, ultimately, felt fully supported and successful. I got what foreign born-students anywhere needed the most, which was to feel welcomed in our new community and our school.

When I came back to the States, I experienced another sense of displacement. I missed the friendliness of the neighbors, the tight-knit neighborhood of Dooreshahr. I missed visiting villages, seeing sheep and goat herders sharing the street with cars, hearing the Adthan wafting through the air. And I was even further lost when I enrolled at my neighborhood school. I was shocked to enter Overbrook High School, with what seemed like 3,000 students, to have to correct my math teacher’s lessons or to see that another teacher drank alcohol during the day to cope with the stress of “educating Black kids.” A version of that disconnect is the same thing immigrant students experience today, in schools all over the country.

Something I think about every time a foreign-born student enters my high school is not how to assimilate them quickly, but how to help them thrive in America while honoring where they came from.

My experiences as an expatriate—and then again, as a new high school student in America—have given me a unique perspective on one of the most pressing educational issues in the country: How to educate immigrants and refugees, especially in this heightened political climate. It’s something I think about every time a foreign-born student enters my high school—not how to assimilate them quickly, but how to help them thrive in America while honoring where they came from.

Today, educators around the United States and the world are grappling with how to make our students who are refugees and immigrants feel welcome in the face of staunch administrative hostility. We know that language acquisition and literacy are crucial aspects of navigating cultures, and that we need to show respect for the bi-lingual abilities of many newcomers. Previously, educators oppressed immigrant communities in schools, demanding that they shed their identities in order to be fully “embraced” within their communities—a “melting pot” is what they called it. This was a form of violence and I am grateful that the research is catching up to what student-centered educators already knew: Deficit-based mindsets are oppressive to any child, especially those already battling significant circumstances.

In January of 2017, I was invited to travel to Poitiers, France with the Department of State and IREX, “an independent nonprofit organization dedicated to building a more just, prosperous, and inclusive world by empowering youth, cultivating leaders, strengthening institutions, and extending access to quality education and information.” The irony of traveling to learn and contribute in a conference themed, “How Schools Can Support Immigrants and Refugees” and returning to America a week before Trump’s inauguration, was not lost on me or the other participants.

At the conference, educators from around Europe and the United States joined together to share how our schools support immigrants, refugees, and other at-risk students. For example, in Minnesota, the district works to hire teachers who share the language and culture of immigrants to support the students and, just as importantly, to educate the staff. Scotland’s school-based summer camps help students access their new world, supporting their language acquisition, exposing them to new art forms, fishing and bike riding. They schedule these summer camps prior to the school year, so immigrant students could become acclimated by day one.

While some of my European counterparts lamented that their countries were not inclusive, others had found ways to help immigrants and refugees integrate into society. Unfortunately, there was an apparent push for new arrivals to shed their culture, language, and customs to fully embrace those of their new hosts. One participant said that immigrants to Europe should try hard to “become a melting pot, like America.” I reminded them that although America’s rhetoric is one of a melting pot, many of our new arrivals have always, and justifiably, resisted the requirement to melt away their identities. America, at its best, displays equity, justice and receptivity to difference. But all too often in schools and outside, that is, unfortunately, more theory than action. I shared with some of my European peers that plenty of immigrants and refugees in America would easily be able to relate to James Baldwin’s words, “I can’t believe what you say, because I see what you do.”

Being a contributing member of two or more cultures is an integral part of a child’s identity, and diversity makes our society stronger. Educators should embrace it. In recent years, I have had students, several of whom were immigrants or children of immigrants, hoist flags from their home countries during graduation, and I encouraged them to do so. I was delighted to see Black children from across the diaspora hold up flags from all over Africa and the Caribbean. I was happy that they didn’t see a need to “ask for permission” to do so and that they found ways that they felt comfortable with to express themselves.

A few years ago, we happily welcomed some Iraqi families into our community. Although, this was not the first time we had the honor of educating immigrant youth from war-torn countries, this was the first time the students arrived in a group. The children were from three different families. They shared stories about their family members being murdered, the intensity and hardship of making it to refugee camps in Syria and Iraq. They contended with the permanent feeling of insecurity that follows children exposed to trauma.

We were determined to ensure these five students found a warm, welcoming, and empowering community. We were not their first Philadelphia school, and we recognized the enormous responsibility we had to ensure they were ready to navigate their new circumstances. We collaborated with the University of Pennsylvania to engage researchers on language acquisition and professional development to support our teachers. Our newly hired English as Secondary Language teacher and tutors worked tirelessly to ensure our new students were progressing.

In taking a stance for equity and justice, many are providing a beacon of light—not just for immigrants and refugees, but for America’s educators. As educators, we can perpetuate racism, biases, and other forms of oppression. Or we can embrace our roles as being rooted in justice and equity. This social justice mindset must extend to how we treat all our students, no matter where they were born.

Today, these students are high school graduates, and are succeeding. Some have moved to California or Canada for opportunities to be reunited with members of their families. Several of them are married with children of their own, enrolled in college, or already working. At Shoemaker, we will always be grateful for being in a position to serve and learn from this experience of welcoming these students. All really means all.

Fortunately, there are many educators who are aligned with the values we profess. Some like TNTP, Education Leaders of Color (EdLoC) and others have provided resources to support our school communities in being just, responsive, and communal for some of our most vulnerable populations.

In taking a stance for equity and justice, they are providing a beacon of light—not just for immigrants and refugees, but for America’s educators. As educators, we can perpetuate racism, biases, and other forms of oppression. Or we can embrace our roles as being rooted in justice and equity. This social justice mindset must extend to how we treat all our students, no matter where they were born.

Sharif El-Mekki is the principal of Mastery Charter School–Shoemaker Campus, a neighborhood public charter school in Philadelphia that serves 750 students in grades 7-12. El-Mekki will be contributing regular columns from the school front lines this year.

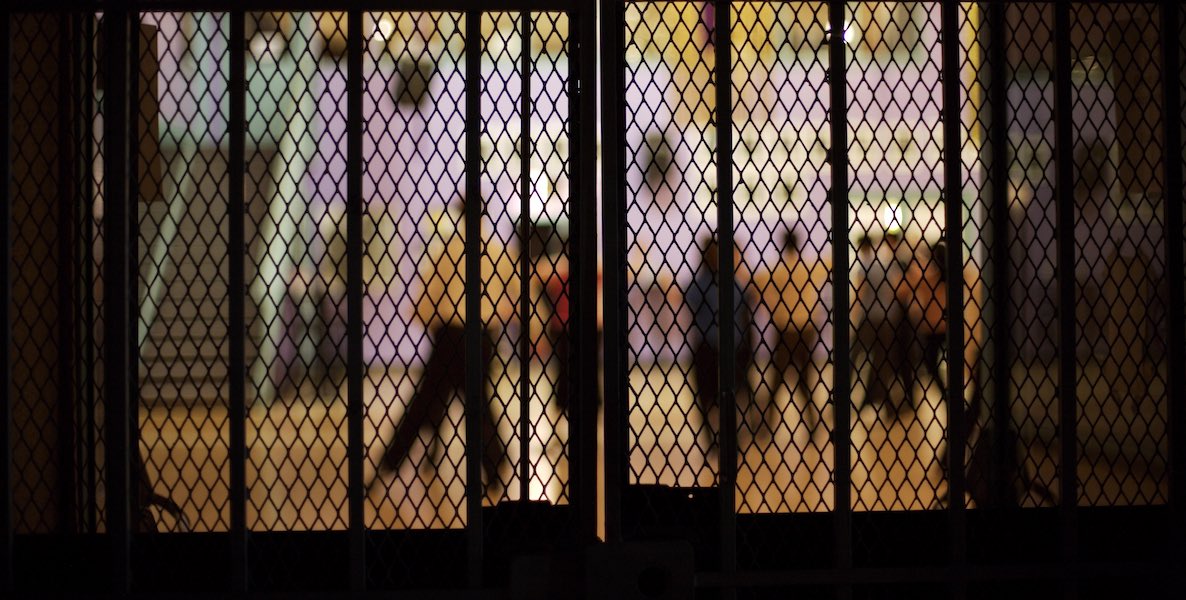

Header photo by Russell Watkins via Department for International Development Flickr