In a City of Neighborhoods, there’s a thought that invariably occurs to all communities at one point or another—be it over informal chats on our stoops, or during structured civic meetings—as neighbors watch lots fall into disrepair, or resent the tenancy of characterless wireless companies and ATM vestibules:

If only the neighborhood could rally to adopt those spaces!

It’s that battle cry that led residents in Northeast Minneapolis to do just that: In 2011, 39 motivated citizens—who’d come to know each other through, and had been inspired by the success of, their local food co-op—banded together to form Northeast Investment Cooperative (NEIC), enabling residents to collectively purchase, improve, and manage commercial and residential property along Central Avenue, their unofficial Main Street.

Prefer the audio version of this story? Listen to this article in CitizenCast below:

Before she joined NEIC, O’Connor Toberman and her husband used to armchair-quarterback neighborhood development: “Now we can play an active role in shaping the neighborhood.”

“It was the recession—values were depressed, there were a lot of vacant spaces, some buildings were eyesores, and many of them were owned by people who didn’t live in the neighborhood, and so the level of care and attention to buildings wasn’t always as high as we’d like it to be,” explains Colleen O’Connor Toberman, a Twin Cities native and NEIC member who moved to the neighborhood in 2010 and recently served on the group’s board.

![]()

Bylaws for the new co-op stipulated a minimum investment of just $1,000, making buy-in accessible in a community that had historically been working-class and had only recently become trendy-but-affordable—as Northern Liberties, then Fishtown, and now Point Breeze were, and are, here.

By the end of 2012, NEIC had grown to 90 members who prepared to buy their first property: a retail space adjacent to a bike shop, whose tenants would be a brewery and a bakery. In 2015 they returned a profit (from rental income) to members, and soon after bought another space.

![]()

As an all-volunteer nonprofit, O’Connor Toberman says NEIC doesn’t have the bandwidth to conduct reports on if or how their investment has affected metrics like average household income or tax redistribution among the neighborhood as a whole. But other benefits are clear.

“We took a building that was essentially vacant and now provides a few-dozen jobs. Buildings are nicer, there are fewer vacancies, most businesses are doing really well,” which has created a more vibrant street life, O’Connor Toberman says. And the change, she adds, has had a ripple effect: There has been a marked increase in the number of commercial properties owned locally around that first building, including several that have been bought by neighborhood residents. That, in turn, has led to better property maintenance, community connection, and business success along the corridor.

![]()

Minnesota has more co-ops than any other state in the country; Land O’ Lakes is probably the most well-known, and the brewery now housed in an NEIC building is itself a co-op. The food co-op through which the founding members knew each other, East Side Co-op, had for years been a community anchor in the neighborhood, and O’Connor Toberman says the idea to start NEIC spread among the founding group organically. Several of the initial members then visited every business on their part of Central Avenue—there are dozens—to share the idea, get feedback, and recruit others. Info sessions and the community newspaper was integral to spreading the word as well.

Like Minnesota, Philly has a rich history of co-ops, including several groceries, housing complexes, pre-schools and workers collectives. And like Minneapolis, the city has a number of commercial corridors in need of local revival. That’s in part why real estate developer Ken Weinstein founded Jumpstart Germantown, an organization that trains and funds neighborhood residents to become developers in their own rights.

Weinstein points out that what NEIC is doing is really not that much different than what a community developer does. “It’s just that they’re using money from many more sources,” he says. “I think this could be a great model for what people would like to do in some of Philadelphia’s neighborhoods.”

In some ways, NEIC’s efforts are a step further than the work of organizations like the Womens Community Revitalization Project, a nonprofit working with residents in Point Breeze and Grays Ferry to create neighborhood plans based on what they need and want to see in their communities. (WCRP is the inaugural winner of the Jeremy Nowak Innovation Award.) Where those residents are putting ideas down on paper, to help direct outside developers, NEIC members had the money and put in the effort to jumpstart a commercial revival themselves.

There are unintended consequences of this work, though. NEIC’s experiment—in tandem with a stronger economy—has led to an increase in the cost of commercial buildings along Central Avenue, which has made developing additional projects more difficult. And eight years after it launched, Northeast Minneapolis is facing similar issues to those experienced in other nearby Minneapolis communities, and in Philly when neighborhoods undergo transition: Prices in the area are going up and selling more quickly, making it less affordable for lower-income residents.

“Especially as neighborhoods change, in positive or negative ways, having people who are invested and paying attention and have a sense of the local neighborhood is so important,” O’Connor Toberman says.

“Just because you want to develop real estate without gentrification does not mean that’s going to happen,” Weinstein cautions. “Because, almost by definition, if you remove blight in a neighborhood, which is a great idea, you are going to drive up property values for the rest of the neighborhood. We all face it; gentrification is real. And it’s going to happen whether or not you are trying to make it happen.”

![]()

O’Connor Toberman notes that their two buildings, which house several businesses, have helped to provide a (albeit small) counter to the rising prices. “We have an opportunity to be a bulwark against too-high rents for local businesses, at least in the buildings we own,” she says. And the group is now trying to grow to include more community members, so more people are benefiting from the growth of the area, and also working to protect its character. “Especially as neighborhoods change, in positive or negative ways, having people who are invested and paying attention and have a sense of the local neighborhood is so important,” she says.

Before she joined NEIC, O’Connor Toberman and her husband used to, as she says, armchair-quarterback neighborhood development: “A business would close and we’d be like, ‘Oh, we need a bike shop there!’ But we didn’t know how that happened, we didn’t have a way to help make it happen. Now we understand how it happens, and we can play an active role in shaping the neighborhood.”

Most importantly, she emphasizes, co-ops like NEIC ensure that, unlike real estate corporations that focus solely on the financial bottom line, community co-ops think beyond the numbers. “We are owners who have a long-term interest in the health of the neighborhood and not just the financial bottom line,” she says.

They recognize that there are multiple bottom lines—and that’s a sentiment that any neighbors, be they in Rittenhouse condos, Brewerytown rowhouses, or beyond, can all get behind.

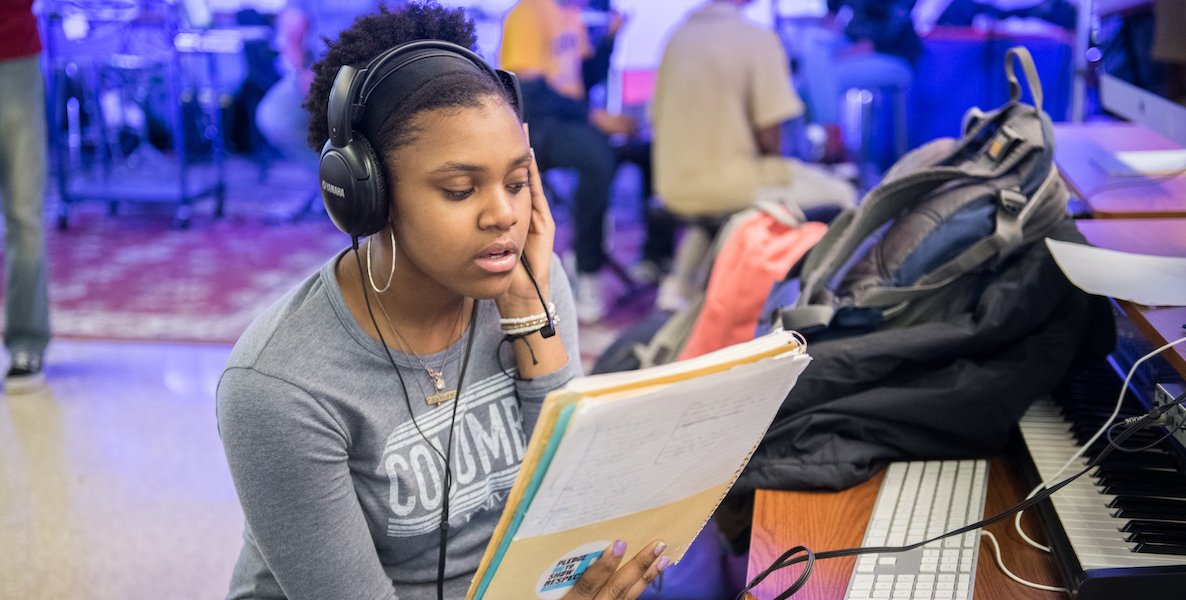

Photo via Northeast Investment Cooperative