Hurt people hurt people, the saying goes. It is an oversimplified shorthand that resurfaces in conversations around school bullying and domestic violence, guns and terrorism. In Philly, it came up recently in the wake of the November 17 verbal and physical assault on Asian-American students headed home from Central High School via SEPTA.

But, says Josh Staub, director of Restorative Programming at the School District of Philadelphia’s Office of Climate and Culture, the converse is also true:

Healed people heal people.

Staub would know. Growing up in Hanover, PA, he had a tumultuous childhood, chronic trauma underlying his regular involvement with the criminal justice system. When he was 21, he was arrested, for possession of an illicit substance, for what would prove to be the last time.

At the insistence of family, he agreed to get his degree. He graduated from college, got a soulless job in Corporate America, then decided to course-correct: Inspired by his beloved grandparents, both retired educators, he set out to pursue teaching.

“Restorative justice is a paradigm shift in the way that we see the world,” says Dr. Teiahsha Bankhead.

On his first day, he was tasked with being a substitute teacher at Paradise School for Boys, a juvenile detention facility in Abbottsville, PA. “I went in there, and all these kids were just like me when I was that age, going through the same things,” he says. “And it was a wonderful day. I loved it. I left there feeling like This is it. I’m gonna do this. And all of that led up to teaching in the areas that need the most love.”

He moved to Oakland, CA, working with traumatized students who’d committed violent acts in schools and had been relegated to special education because of their behavior. Fortuitously, while in Oakland, he met David Yusem. Yusem is the leader of restorative justice programs for Oakland Unified School District, the widely-heralded gold standard of in-school restorative justice, or RJ, as practitioners call it.

Yusem’s leadership has generated the kind of metrics that make funders and academics drool: Early into his work in Oakland, for example, Berkeley researchers tracked the impact of RJ interventions in schools and reported an 87 percent decrease in expulsions. Subsequent evaluations reported that suspensions for African-American students for disruption/willful defiance decreased by 40 percent in one year; and the Black/White discipline gap, that pervasive discrepancy between the rate at which Black students are disciplined versus their White peers (for the same alleged infractions), went down too. The percent of student participants who were suspended over time dropped by half, a rate of change that was more significant than it was district-wide or for non-RJ students.

But ask anyone who does the work and they will insist that RJ is best evaluated by qualitative measures—stories of, say, teens who take it from the classroom out into the school hallways, to their homes, to the streets.

But what even is RJ? And how could it pave the way to eradicate the kind of violence we saw on November 17 on SEPTA, and that our communities witness every day?

A multi-tiered approach

There are misconceptions about the term “restorative justice.” You may associate the phrase with mediation, with working through a tragedy or in reaction to a crime. Others might conflate it with mindfulness, or with healing arts- and sports-based interventions—which are wonderful, full stop, but are not as holistic as RJ. Because the heart of RJ, when done properly, is not reactionary, but proactive.

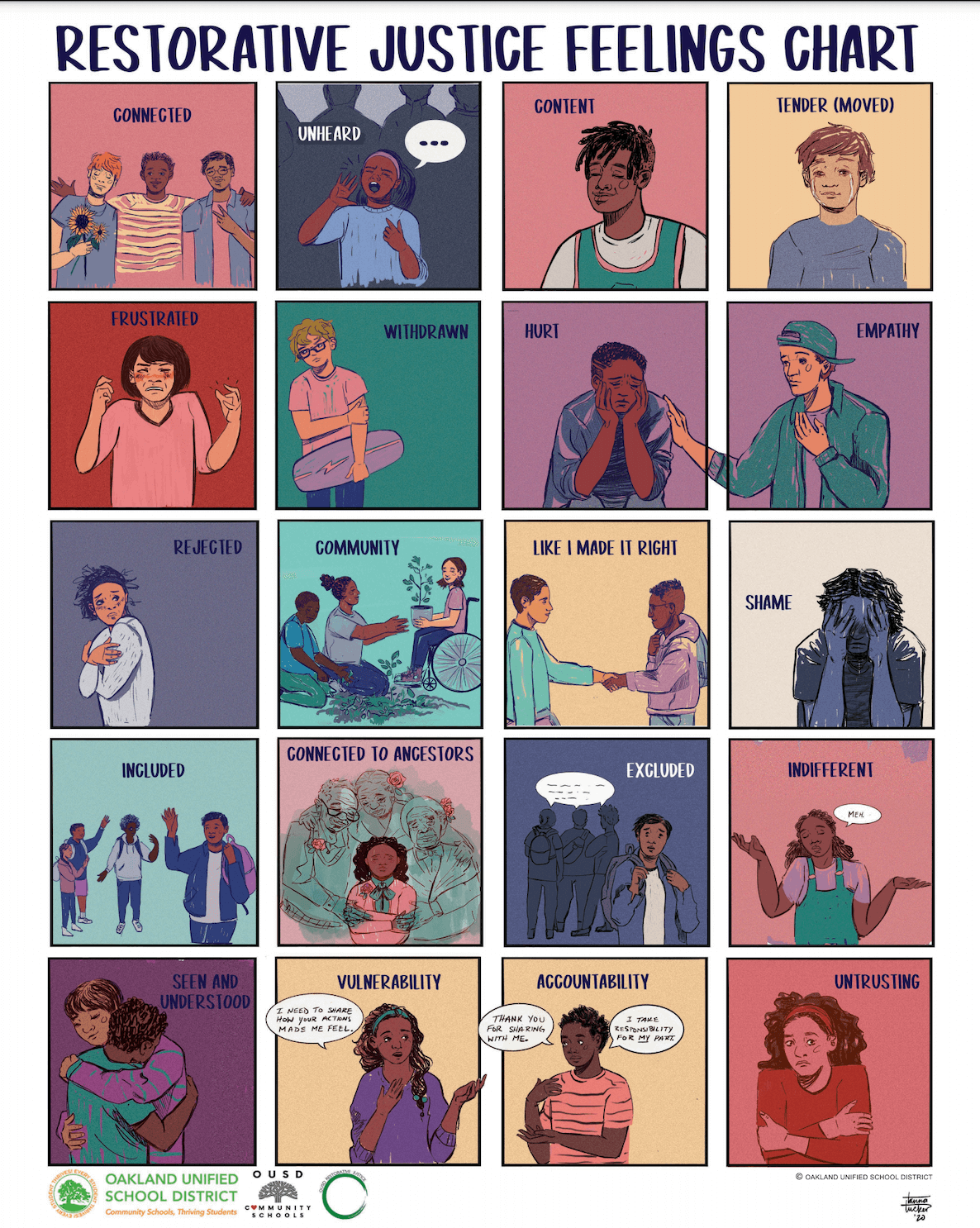

Rooted in the ancient ways of indigenous people, it’s about relationship-building. In the Oakland model—and now here in Philly—there are three tiers of restorative justice. This multi-tiered system of supports, outlined in Dr. Fania Davis’s must-read book, The Little Book of Race and Restorative Justice, boils down to three Rs: relate; repair; restore.

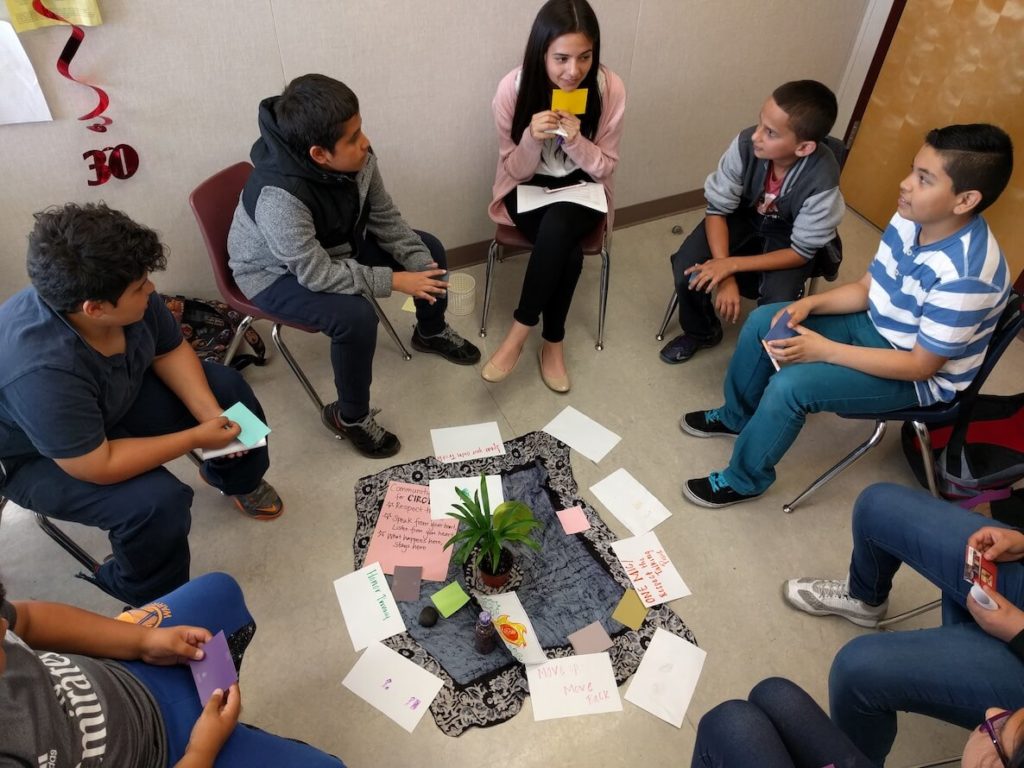

Tier 1, relate, explains Yusem, is about proactively using RJ as a way to build community; maintain that community; to be in relationship with each other; to “work with,” not “do to;” and to create the environment in the classroom and in the school where teaching and learning can happen. It’s about creating a culture that’s inclusive and welcoming, and it involves regular “circle work,” bringing groups together to speak and listen while sitting in a circle, following protocols that foster equality, safety, and community.

Schools that practice RJ might begin each day with, say, a 15-minute circle for teachers, led by a designated colleague, to answer a specific question: What was the hardest part of yesterday? What are you feeling hopeful about? The magic comes as people go beyond the transactional nature of work relationships, and start to empathize and relate. Heading into the classroom from there, those same teachers may designate a student to lead a student circle, also responding to a prompt: What’s the hardest part about being a teenager? What’s the best part?

Tier 2, repair, is what most people think of when they think of RJ: It’s about resolving conflict or responding to harm in a way that repairs harm, rather than pushing people out of the school or isolating or excluding them from the educational environment. Instead of expelling student X for, say, vandalizing a locker, it’s about inviting student X into a circle to ask what they were feeling, why they did that, and to hear from the rest of the students in the room about how it made them feel.

Tier 3, restore, is about individual support for one student or adult who needs it. If a student was incarcerated and they’re returning to school, for example, RJ would focus on welcoming them back and identifying what support they need.

To watch the videos on Oakland Unified School District’s site, particularly those featuring teens leading the circle process, you can’t help but put your cynicism to the side. Because the skeptic’s question is naturally: What good is all this touchy-feely stuff in school if kids are leaving the building to walk violence- and drug-riddled streets?

“What we know from a lot of research, and I know this from experience, is that one way to interrupt chronic trauma is through relationships that are strong, authentic, loving, and safe,” says Staub.

But, says Yusem, that framing is reductive: RJ not only creates a safe space in school, but imparts transferable skills outside of it. It creates a culture shift. “Skills like self-awareness, self-regulation, self-management, social awareness, responsible decision-making—those kinds of skills are necessary for life, and doing RJ in the classroom supports those skills,” he says.

Staub can attest to this, professionally and personally. “I’m someone who grew up in hell, living in a place where trauma is not just deep but it’s chronic,” he says. “And what we know from a lot of research, and I know this from experience, is that one way to interrupt chronic trauma is through relationships that are strong, authentic, loving, and safe. And [with RJ] we cultivate space for that.”

Staub arrived in Philly in 2017 and started using RJ practices while working with students in Kensington who’d committed grave, often violent, in-school violations; over the course of his year with them, violence went down 100 percent.

Now, he leads a 15-person coaching staff that works out of a center in Kensington’s John Welsh Elementary School; this school year, his team launched an RJ program in 54 schools called Relationships First (RF) based on the multi-tier Oakland model.

As the annual school planning process is going on right now throughout the District, more and more schools are clamoring for it; Staub envisions doubling to twice as many schools by next year. (The program does currently support Central, where the SEPTA victims go to school, and it also supports South Philly High, which in 2009 was the site of horrific anti-Asian attacks.)

Schools that are implementing Relationships First follow a sequence beginning with a meeting with school leadership about their needs and goals. After designating a “resident expert” who will ultimately train the rest of the staff, schools begin with tier 1 practices, move to tier 2, then tier 3. “This is going to take schools multiple years to fully implement,” Staub acknowledges. Currently, the District has one school, Bayard Taylor, implementing all three tiers along with restorative, progressive discipline.

Restorative Cities

“Restorative justice is a paradigm shift in the way that we see the world,” says Dr. Teiahsha Bankhead. Bankhead is the director of Restorative Justice for Oakland Youth, RJOY, the youth nonprofit that first partnered with Oakland Unified to launch RJ in schools. Its programming goes beyond school-based programs, now, and exists citywide.

Bankhead’s goal is to make Oakland more like Hull, England, the world’s first modern RJ city, where schools, police departments, and youth services all use RJ. Police there, for example, use it to resolve neighborhood conflicts, like in one case in which an elderly woman in public housing had “complained to police hundreds of times about young people’s noise and profanity. A police-led conference with local youth and the woman stopped [it].”

“Skills like self-awareness, self-regulation, self-management, social awareness, responsible decision-making—those kinds of skills are necessary for life, and doing RJ in the classroom supports those skills,” Yusem says.

Most schools, organizations, and families come to RJOY looking for tier 2 interventions, because there’s been a harm, conflict, some hurt that has happened, Bankhead says. “They want to resolve that pain,” she says. “They want a restorative justice conflict circle. And we will do that with folks, but what we tell them is that the more tier 1 work you do, the less of the other you ever have to do.”

RJOY currently holds about 10 community RJ circles around the city each week: Bankhead estimates that for every five harm circles RJOY facilitates, they facilitate 90 proactive circles. There’s a queer and trans people of color circle, a sisters circle, a Black male circle, formerly incarcerated people circle, youth circle, elder circle, and so on. In Oakland, RJ is in schools, communities, and institutions that are necessary for structures: the police systems, the child welfare system, the mental health system, the homeless support systems.

Bringing it to Philly

Staub likes to think of his work in Philly as an extension of what Oakland is doing, and he’s hopeful that it will grow. But he is not naive: He knows RJ is not some magic wand that will cure our city’s many (too many) ills. But it represents the potential for deep change—of eliminating incidents like the SEPTA attack, of moving forward meaningfully in the wake of incidents like it.

He believes there are really no barriers other than walls that separate community from school. “It’s all permeable,” he says. “Communities are made up of people. And so imagine the classroom becomes a safe space where people can breathe; then the school becomes that, a safe space where people can breathe—not just the students, but the teachers that work there, the parents that interact there; and that begins to permeate out. Because what happens in a space that’s sort of free from that toxic stress, what blossoms are human relationships.”

There are two sides to education, really: “One side of it is giving you information, understanding how things work,” Staub says. “Understanding the mores and roles of society, being able to function in society even if society’s broken. But the other side of it, which is even more powerful and is rooted in liberation, is this idea of being a critical thinker. Couple that with healing, and that is just a beautiful thing.”

There are two sides to education, really: “One side of it is giving you information, understanding how things work,” Staub says. “Understanding the mores and roles of society, being able to function in society even if society’s broken. But the other side of it, which is even more powerful and is rooted in liberation, is this idea of being a critical thinker. Couple that with healing, and that is just a beautiful thing.”

In the days after the SEPTA attack, hundreds of folks, including students from Central and Masterman and more, attended a rally across from City Hall, holding signs with “Brotherly love for our students” and “Stop Asian Hate!!” emblazoned upon them. Soon after that, 15 community organizations issued a statement saying:

At this time, we call for: 1) Centering the healing of the harmed youths and accountability for responsible youths that is healing and transformative, NOT punitive, retributive, or involving the traditional juvenile justice system; 2) Centering the voices and demands of our young people. Too often we have moved at a reactionary pace, disregarding what our impacted youth have said what safety, healing, and justice truly means for them. We must listen to the demands that our youth leaders have made for years, and we must listen to what demands they will make from here on.

In other words? Restorative justice—to heal; to relate, to repair, and to restore.

Yusem, Staub, Bankhead, all believe it’s possible. Of course, when I tell Staub about the experts I’ve talked to for this piece, the books I’m reading and papers I’m animatedly highlighting, he cautions me.

“We’re a subset,” he says, not yet the majority or mainstream philosophy in modern education. “So I guess my big message around restorative practices in general is it is not monolithic whatsoever. And there are restorative practices which to me are very different than restorative justice. And these are not the same thing.”

Restorative justice has at its root ancient ways; as its wings civil rights; and, done well, a racial justice lens. “What we’re really pushing for,” Staub says,“is community.”

The Citizen is one of 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic mobility. Follow the project on Twitter @BrokeInPhilly.

![]() MORE ON INNOVATIVE PROGRAMS FOR YOUTH

MORE ON INNOVATIVE PROGRAMS FOR YOUTH

https://thephiladelphiacitizen.org/problem-solving-must-reads-youth-lead-reconciliation-process-columbia/

Header photo: In the days after the SEPTA attack, hundreds of folks, including students from Central and Masterman and more, attended a rally across from City Hall | By Jessica Blatt Press