When El Sawyer was 17 years old, he was sentenced to 8 years in Graterford prison for a drug-related shooting. At night, he lay awake in his cell, in fear of a rotating string of cellmates in the bunk above him, thinking about what went on in the prison—the stabbings, killings, suicide, depression, and anger. He believed he wouldn’t live until the end of his sentence, that he would never return to North Philadelphia, where he had left behind a young son.

“I didn’t think I was coming home,” Sawyer says. “I lay there thinking about different ways I could articulate my experience to my son, so he would understand who I was if I died in prison.”

A couple years later, he found it: He joined the prison video team to film events for the internal TV station, started sending videos home to his son, and helping other inmates to do the same for their own children. Making those films saved him.

But on the eve of his release, Sawyer found he was deeply afraid again—of returning home. Now that he’d survived, what would he do? He’d dropped out of school after the seventh grade and couldn’t read; he had never had a job; a good friend of his from the neighborhood had just been killed. He took every re-entry program that Graterford offered, but says they were useless and silly, often just videos of a recently released inmate character, usually a white man, faced with various “challenging” situations he might encounter back home, like two relatives sitting in his suburban living room drinking beer and refusing to leave. These “trainings” were woefully out of touch with the reality of the urban community Sawyer was going home to, in which poverty, crime, unemployment, racism, police violence and other forces outside his control thrived.

Pull of Gravity, has become the catalyst for a change in how we as a culture think about former inmates re-entering their communities. He’s met with Pres. Obama. And in May, he won $100,000 from the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation to develop a program to train police, prisons and parole officers how to better reintegrate former inmates into society.

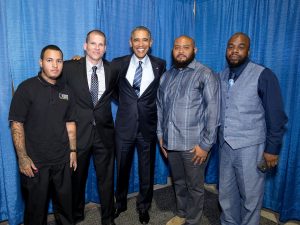

So Sawyer fell back on the thing that had helped him survive Graterford: Filmmaking. Now, thirteen years later, his documentary, Pull of Gravity, has become the catalyst for a change in how we as a culture think about former inmates re-entering their communities. He’s met with Pres. Obama to provide advice on prison reform. And in May, he won $100,000 from the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation to develop a program to train police, prisons and parole officers how to better reintegrate former inmates into society.

“The seed for something big was planted in my fear of coming home,” Sawyer says.

Sawyer’s path from inmate to documentarian began in prison, when local artist Lily Yeh visited Graterford to do a documentary and was denied the use of her film crew. Sawyer volunteered to be her videographer. In exchange, the filmmaker working on the project, Glen Holsten, spent up to three days a week for six years training Sawyer in how to make films.

When he got out in 2003, Sawyer started working at the Village of Arts and Humanities, a community arts organization founded by his old friend Yeh. He taught film to kids and college students, one of whom, Temple student Jon Kaufman, became his collaborator. They shared the idea that teaching film to youth and community members could be a tool for social justice, and an interest in an ambitious project that would engage with the issues they saw over and over again in North Philadelphia—drugs, lack of job opportunity and training, people hustling to survive and getting sent to prison by the thousands.

But more than anything, they saw that people who served time and came home returned to prison in alarming numbers. This is not just specific to Philadelphia. According to data from the Department of Justice, of the nearly 700,000 inmates released across the United States each year, 67 percent will be back in prison in three years—despite the $3.9 billion being spent on re-entry programs each year.

Sawyer and Kaufman founded Media in Neighborhoods Group (MING) Media to teach filmmaking to community members as a way to keep them out of prison. Then, in 2011, Zane David Memeger, the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, gave them $30,000 in department funds to make a documentary film about former inmates re-entering society, as part of his work to find more preventative solutions to crime and innovative ideas for re-entry programs.

Pull of Gravity tells the stories of three men who have returned home from prison and are struggling to stay home, resisting the pull of drug and other illegal work in the face of a community not offering many other possibilities. One of the men was Sawyer; the other two were re-arrested during the time it took to make the film, from 2012 to 2014. Sawyer says there is a fourth character in the film: The neighborhood, which affects the outcome of all the men involved.

“There is a lack of understanding and empathy about what people go through when they come home,” says Sawyer. “That’s what we’re trying to show. Our thing isn’t making films about why people go to prison or mass incarceration in general, per se. It’s to show the atrocities that happen both in and out of prison, the trauma of being in negatively charged environments.”

Sawyer and Kaufman intended the movie to serve as a tool to educate institutions—prison guards and administrators, judges, prosecutors, parole, probation and police officers—on the real challenges facing those who re-enter poor communities after serving time. Ex-offenders have a Goliath task when they emerge from prison: Get a job, secure housing, check in with their parole officer weekly, carry their offender card at all times. Job scarcity or relatives who live in Section 8 housing and cannot take them in (ex-felons are not allowed in public housing) is no excuse. Any minor infraction means they are automatically sent back to prison for 90 days.

“It’s not cool, it’s not fair, to set all these expectations,” says Sawyer. “You’re not considering the people coming home to be human; you’re treating them as if they have superhuman abilities. They have to bob and weave through a minefield.”

“It’s not cool, it’s not fair, to set all these expectations,” says Sawyer. “You’re not considering the people coming home to be human; you’re treating them as if they have superhuman abilities. They have to bob and weave through a minefield.”

Pull of Gravity was screened in February 2013 at the Constitution Center for 200 Philadelphia judges, city officials, and other criminal justice professionals. It has since been screened over 350 times in federal prisons and institutions all over the country. Sawyer and Kaufman regularly show the film and highlight the challenges of re-entry for probation and parole officers in Pennsylvania, as well as for judges in the First, Second and Third district courts.

“While incarceration serves an important societal goal of keeping dangerous offenders off the streets,” U.S. Attorney Memeger says on the film’s website, “the reality is that most offenders eventually return to the community. Without a comprehensive plan which addresses crime prevention and reentry issues, the cyclical nature of crime by repeat offenders will continue.”

Still, Sawyer says he did not expect the his film would start to influence re-entry programs and policies. During the NAACP convention in Philadelphia last summer, President Obama met with Sawyer asking for his input on a new criminal justice initiative looking at reforming mandatory minimum sentencing. After viewing Pull of Gravity, Oakland, California’s offices of probation and supervised release changed the way they operate—shifting the language they used to talk about their participants from “parolee” to “client,” to remind officers that they should be serving and helping ex-offenders re-enter their home communities rather than punishing and controlling them. Sawyer says similar changes are underway in Texas and Florida, after the film screened there.

And the film is exposing other problems in the current policies around re-entry. At United States Penitentiary Hazleton in northern West Virginia, where inmates from Philadelphia and other East Coast cities are regularly housed, Sawyer says a staff person who worked on re-entry for the prison stood up after viewing the film. “I’m not set up to do this work, I’m not given the proper tools,” she told Sawyer. “I’m from this town in West Virginia, I’ve lived here all my life. How the hell am I supposed to get people ready to go back to North Philly?”

That’s a question Sawyer wants to help answer. He plans to use the $100,000 grant from the Rauschenberg Foundation to develop the ideas of the film into a curriculum that can be used as a training tool for police forces, prison guards, parole departments and more. He says the exact nature of the curriculum is still in development, but that he has been in touch with technology companies about creating an app that would offer these institutions constant resources and online coaching. He wants to bridge the gap between the existing programming and the reality of many former inmates’ home communities.

“We have pipe dreams,” says Sawyer. “We dream stuff up, and then we go make it happen.”

Photo header: Courtesy of Jared Gruenwald Photography