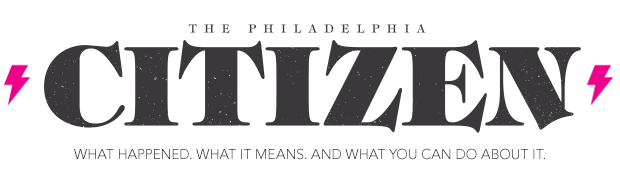

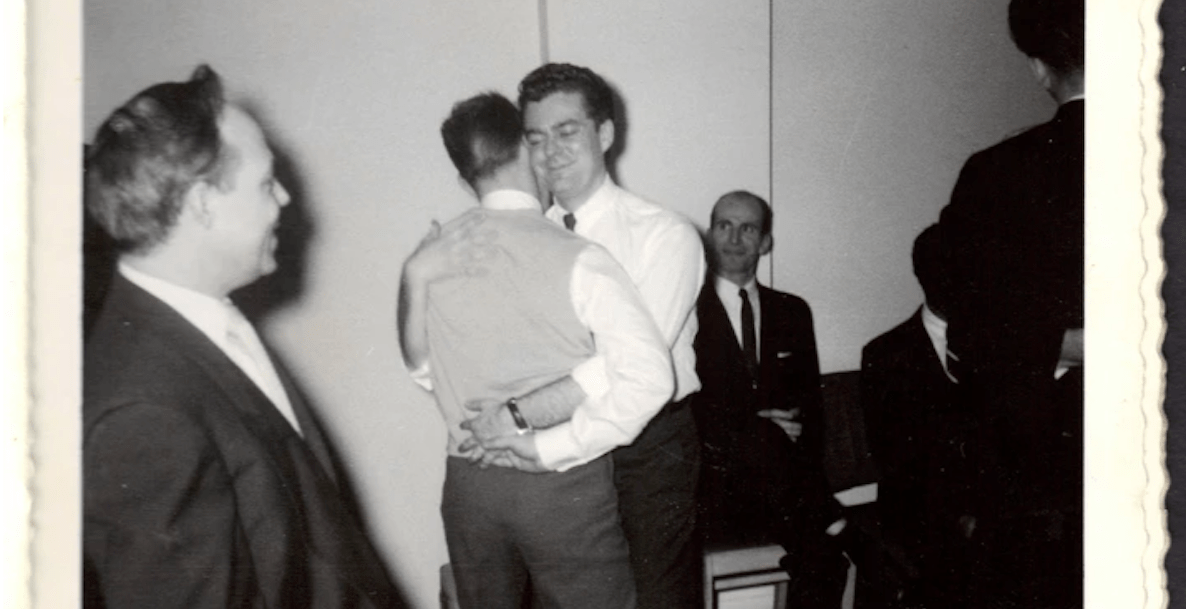

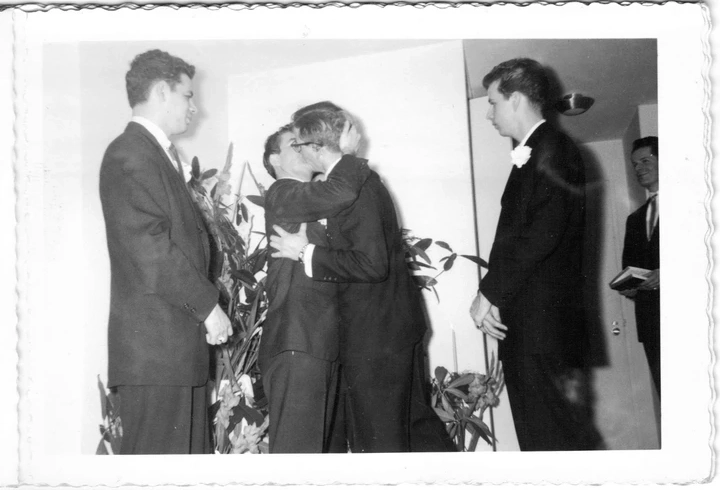

In 1957, a young man went to a photo shop on the corner of North Broad Street and Allegheny Avenue to have his wedding photos developed. The photos captured the usual moments: the exchange of rings in front of witnesses, the first kiss and dance, the cutting of the cake and the opening of gifts.

Prefer the audio version of this story? Listen to this article in CitizenCast below:

But the young man would never see them. That’s because the photos depict him in a commitment ceremony with another man, and unbeknownst to him, the store manager had a policy of withholding developed photos if he deemed them “inappropriate” — as he did these.

The photos, though, lived on because the manager of the shop had another policy: Staff were allowed to do whatever they pleased with confiscated pictures. An employee held on to the photos, which her daughter discovered in her Cherry Hill home 60 years later, after she passed.

“My mother had a somewhat photographic memory for faces and retained these in the event the customers who dropped them off ever came back to the shop so that she could give them to the customers on the sly,” she wrote in a letter to the ONE Foundation, an LGBTQ archive in Los Angeles.

In 2013, she sold the photos on eBay to a donor who later gave the photographs to the ONE Archives in Los Angeles and the John J. Wilcox Jr. Archives in Philadelphia. Since then, the organizations have been looking for the grooms, their friends or family. In the photographs, the two men and their friends appear to be mostly in their twenties and thirties; if they are alive today, they would be in their eighties or nineties. Archivists have reached out to local business owners and elder LGBTQ Philadelphians. But so far, their efforts have been fruitless.

“There are so many unidentified people in our collection—it is a frustrating part of our history,” says Oliveira. “There were people who feared violence, having their houses burned down, because they had their name in the newspaper. And these retaliations did happen; sometimes they were government sanctioned.”

“It’s a needle in a haystack — there’s too many questions and not enough information about this photo collection,” said Michael Oliveira, an archivist at ONE. “While many people and families tend to stay put in the Delaware Valley area, we can speculate about where they were taken, who took the photos and so much more — and never arrive at an answer.”

As last month’s celebrations of the 50th Anniversary of the Stonewall uprisings made clear, the fraught history of LGBTQ Americans is having a moment. John Anderies, director of the Wilcox Archives at the William Way LGBT Community Center, says seniors are more willing to donate and preserve their collection than any other age group, and both ONE and the Wilcox have troves of ephemera, photographs and clippings of LGBTQ life throughout the 20th Century. On Instagram, there’s even an account — @lgbt_history — that has nearly half a million followers.

But even with this eagerness and increased attention, there is a wide gap of knowledge and lived-experience between the eldest and youngest members of the LGBTQ community. “There are so many unidentified people in our collection — it is a frustrating part of our history,” says Oliveira. “There were people who feared violence, having their houses burned down, because they had their name in the newspaper. And these retaliations did happen; sometimes they were government sanctioned.”

As personal as these wedding photographs are, they also reveal a lot about the time period in which they were created. The photos are taken in what appears to be a private apartment with the blinds and curtains drawn, out of the public eye, perhaps for fear of discrimination and violence. Still, they contain images of joyful celebration, of dancing and laughter. They also may include some clues: A gathering of gay men may indicate the couple worked in professions where homosexuality was more acceptable, like hair stylists and artists. And one man is in drag. “Drag only happens in community and is done with other people who also do drag,” says Anderies.

The search for the happy couple is also a way for researchers to get more information about LGBTQ life of the mid-20th Century from living members of the community, often through events William Way hosts at the John C. Anderson Apartments, Philadelphia’s LGBTQ-specific affordable housing project.

“The 1950’s time period is rapidly becoming inaccessible because we’re a generation removed, and there are only a handful of men—of gay men—from Philadelphia in their 90’s that are alive,” Anderies says. “The intergenerational exchanges we have during these events are invaluable. It’s an amazing transfer of knowledge between generations. I love mining their experiences, even if we cannot return these photos to the men or a living family member of theirs.”

![]()