Thursday morning. Two days after the end of one great national nightmare—the 2016 presidential campaign—and the start of an even greater struggle: Healing. What does that even look like? What it isn’t, what it can’t be, is a continuation of the deplorable nasty name-calling; it can’t be a doubling-down of threats and accusations and media hysteria. It may require as unprecedented an experience as this entire election season has been, a complete reversal of the way we’ve been talking, and thinking, and relating to each other. It may require trying to understand the other side.

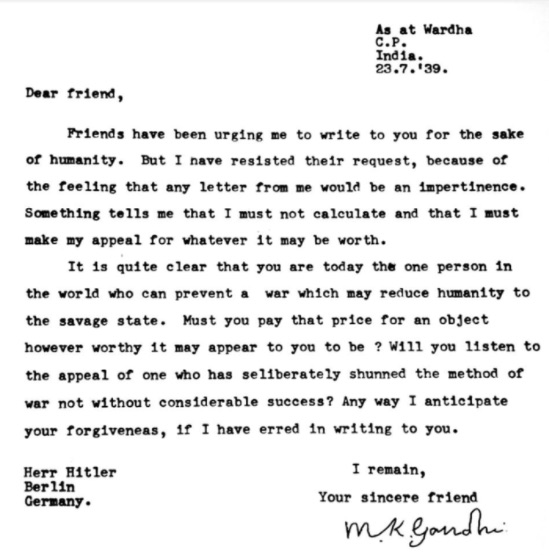

Yes, that will be hard. And yes, these are hard times for our republic. But let’s be clear: As hard times go, we still don’t live in war-eviscerated Syria, or in Afghanistan—or in 1939. That was the year when all of Europe was on the brink of war, threatened by a tyrant who could still, perhaps, have been stopped before it was too late. And so it was that from across the world, a single great man, Mahatma Gandhi, made a historic plea for peace, in a way almost unimaginable today: by appealing to Hitler’s humanity.

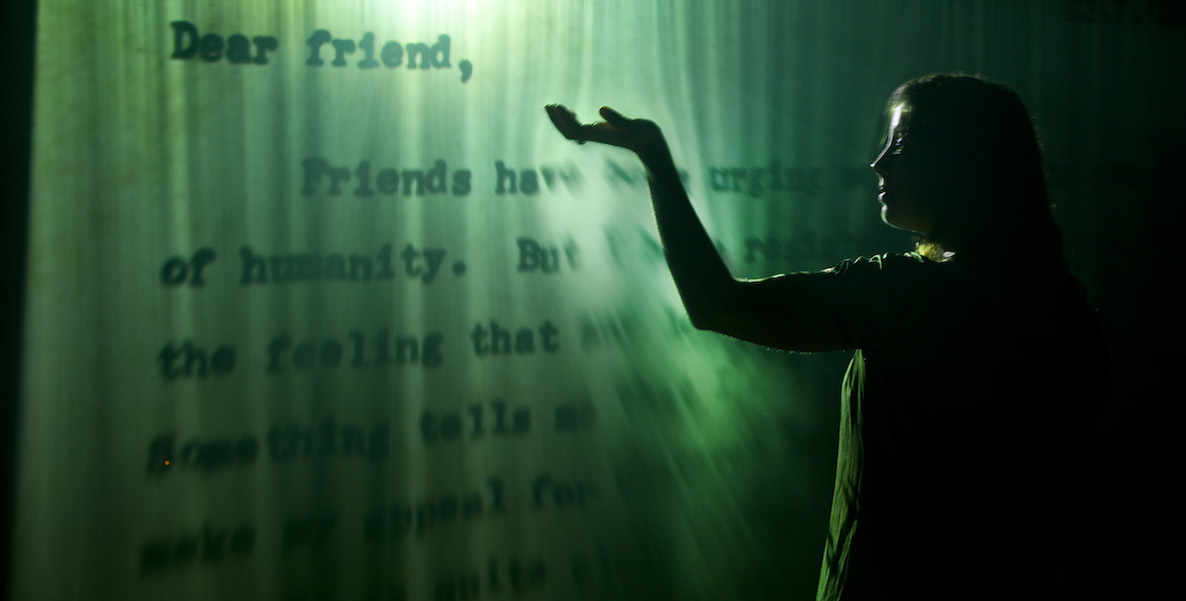

That note is the basis for Jitish Kallat’s Covering Letter, an installation exhibit donated to the Philadelphia Museum of Art by the Pamela and Ajay Raju Foundation, and for a high school essay-writing contest the Foundation is launching this week with The Citizen and 6ABC. (Ajay Raju is co-founder of The Citizen.) Raju, CEO of Dilworth Paxson and a philanthropist who sits on the PMA’s board, bought the piece in the spring (before the height of the Presidential election). He was moved, he says, by the embodiment of absolute peace urging the embodiment of absolute war to stand down, and was struck particularly by the words that start and end the letter: friend.

“I don’t think Gandhi thought with those mere seven sentences he’d convince Hitler to reverse course,” Raju says, noting that the British intercepted the missive so it never got to Hitler. “He was writing a letter to humanity—to Martin Luther King, and Nelson Mandela, and SEPTA strikers who protested without violence; for that bully to reconsider in sixth grade if he should bully; for Donald Trump; for the commenters on philly.com; for all of us who have a Hitler and a Gandhi inside of us.”

In the essay contest, for which one entrant will win a $10,000 scholarship from the Raju Foundation, we’re asking high school students to apply the themes of Covering Letter to their own lives.

Covering Letter is the first piece of Indian art that will be included in the Museum’s permanent contemporary art collection, rather than part of the South Asian department. It’s part of the PMA’s effort—led by Raju—to make Philadelphia a hub of Indian contemporary art, and to broaden the Museum’s holdings beyond the European greats. On display until March at the Perelman Building, the piece consists of a dark hallway, at the end of which the words are projected onto a screen of continuously falling mist.

An avid collector of Indian art, Raju encountered Covering Letter with the artist while on a trip to India, and had an immediate emotional reaction, at first to the mist. “The Catholic in me thought this must be what it is like when you’re called up to Heaven,” he says. Later, Kallat told him about another viewer’s reaction: “He saw it as representing Hitler’s gas chambers.” This contrast, Raju says, is part of what is magical about the work. “It’s really an individual experience,” he notes. “Within our own hearts, we have pessimism and optimism. I’m not convinced one side is right or wrong. I stand with Gandhi, that the long arc of peace is right. But some take a different approach.”

In the essay contest, for which one entrant will win a $10,000 scholarship from the Raju Foundation, we’re asking high school students to apply the themes of Covering Letter to their own lives, answering two questions:

- In this era of social media, in which modes and methods of communication are more abundant than ever before, what can Gandhi’s letter tell us about how we interact with those who disagree with us?

- Is the written word now just a means to lob rhetorical grenades, or is there hope for seeking common ground with our opponents with language that appeals to our shared humanity?

The contest is open to any high school student in the region, and will be judged by a group of journalists and other local figures. The prize will be awarded at a closing ceremony event at the Museum in March. But Raju intends for students to see the exhibit before then, as inspiration for their essays and their lives. Any student who brings to the PMA a hard copy of the essay prompts—which will be sent to all area high schools—will get two free tickets to the Museum, to see the piece. In this way, Raju hopes to open the Philly art scene to a new world of young people. “I’m hoping whole new neighborhoods of Philadelphians will find the Museum,” he says. (Read Raju’s essay inspired by Covering Letter here.)

“Gandhi was writing a letter to humanity,” Raju says, “to Martin Luther King, and Nelson Mandela, and SEPTA strikers who protested without violence; for that bully to reconsider in sixth grade if he should bully; for Donald Trump; for the commenters on philly.com; for all of us who have a Hitler and a Gandhi inside of us.”

Gandhi’s letter never made it to Hitler; the British intercepted it. And Hitler, of course, did not stop his aggression. Less than two months later, he invaded Poland, followed in quick succession by declarations of war from around the world. Gandhi abhorred violence of any kind, some say to a fault; non-violent protest clearly would not have stopped Hitler. But he followed up that first short letter with a longer one 17 months later, in which the Indian leader explains why he calls Hitler “friend”:

“That I address you as a friend is no formality. I own no foes. My business in life has been for the past 33 years to enlist the friendship of the whole of humanity by befriending mankind, irrespective of race, colour or creed.”

Is there room in our country for a sentiment like this? If not, then we are truly doomed to a post-election that is no less heartbreaking than the campaign.

Header photo courtesy of Galerie Templon, Paris and Brussels © B.Huet/Tutti.