Chris Banks, the founder of the Philly-based Banksgiving, a non-profit that helps kids better understand personal and business economics, remembers the grind. He was the kind of kid who never didn’t have a job. At 12 years old, he was a paperboy; at 13, he was sweeping up hair at a barbershop; at 14, once he got his working papers, he was doing shifts at the movie theater, mall jobs, the local ShopRite.

Be Part of the Solution

Become a Citizen member.Banks didn’t have much coming up; if he ever wanted any status symbols—fresh kicks, video games—he had to get it himself. And, just like any kid who ever had to bust his or her hump for 20 hours a week at the local supermarket to stay above water, he was constantly working…and constantly broke.

“Every year I had a job. It was money, but as a kid, you only want money to spend on the now,” says Banks. “I would see a lot of money, but I thought that everything that I got, I should spend. And I graduated high school with no money.”

![]()

It took a while for Banks, now 30, to get his financial house in order. Like most of us, he had some gnarly habits that he unlearned after college at Temple, where—as the first in his family to attend college—he studied Political Science and Communications, before a stint as an intern with Mayor Michael Nutter’s administration.

Now a policy analyst for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in Washington, D.C.—to where he commutes from Philly—Banks is on a mission to pass on the lessons he learned the hard way to Philly kids like he was.

![]()

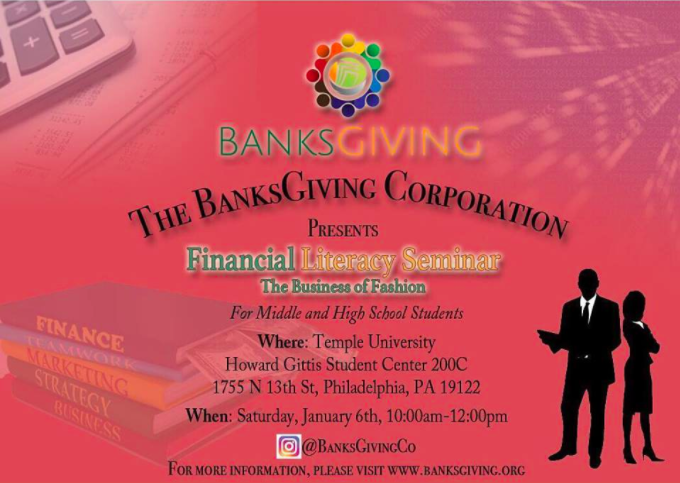

Banksgiving offers middle and high schoolers two-hour long seminars at Temple every few months on how to save, manage and invest money. Since it launched in March, more than 100 students have attended the Saturday morning seminars, and in November, those who showed up for two of the three sessions so far were rewarded with $50 savings accounts, funded by donations to Banksgiving. On Saturday, Banksgiving will hold another program, on the business of fashion, with guest speaker Tiffany Reid, senior fashion editor at Cosmopolitan magazine.

“I thought that it was important that I give kids who look like they come from a similar background an opportunity to learn the things that I know now that I wish I knew then, in the early adolescent or teenage years,” says Banks.

This generation and those that come after are empirically lacking in financial know how. A recent George Washington University study found that only 8 percent of polled millennials were highly proficient at managing their money, and that roughly a quarter had what pollsters would call only “basic understanding” of money management.

Considering the sorry state of financial literacy in this country, and Philadelphia in particular, Banks knows he faces an uphill battle.The cards are stacked against recent generations in ways that previous generations haven’t endured for decades due to, among other things, an absurdly low minimum wage, massive student debt and contracting middle-class job markets. According to the 2013 Consumer Financial Literacy Survey, 26 percent of adults don’t pay their bills on time and 31 percent have not saved anything for retirement. And of the 37 million Americans without bank accounts, Philadelphia has among the lowest rate of residents with simple savings and checking accounts.

Making matters worse, this generation and those that come after are empirically lacking in financial know how. A recent George Washington University study found that only 8 percent of polled millennials were highly proficient at managing their money, and that roughly a quarter had what pollsters would call only “basic understanding” of money management.

For the most part, financial literacy is no longer taught at schools; according to a study conducted by the Council for Economic Education released last year, only 20 states require students to take economics classes. Home Economics classes—which weren’t that great at teaching kids financial skills in the first place (raise your hand if you remember the only form of personal finance you learned in high school being how to balance a checkbook)—are often the first studies to get the cut in budget trimming efforts at school.

That means that the first and likely second generation of modern Americans who are expected to be less prosperous and retire later than their parents are also the most unprepared to handle personal finance, set to navigate the immense and confounding sea of credit, savings and investment without a compass.

That is, unless people like Chris Banks can provide guidance.

Since it launched in March, more than 100 students have attended the Saturday morning seminars, and in November, those who showed up for two of the three sessions so far were rewarded with $50 savings accounts, funded by donations to Banksgiving.

Students attend Banksgiving by choice, recommended by their their schools, parents, and peers. But Banks knows they’re going to tune out if they’re made to sit through a boring lecture on credit management or early investment. The content has to be grabby, and it has to keep butts in seats.

As such, he keeps the lessons punchy, and brings in guest speakers to inspire his pupils after he delivers his monologue on fiscal responsibility, Kyle Billig, the founder of Sweet Charlie’s rolled ice cream, spoke to Banksgiving kids in July about starting his business. Tosin Oduwole, Atlanta-based real estate mini-magnate addressed the group in March about investing at a young age; afterwards, he paid for one of Banks’ pupils to attend a real estate pre-licensing class.

Saudiah Bashir has been to every one of Banksgiving’s events. The 16-year-old high school junior who attends Freire Charter School says that the program is helping her figure out important steps for handling her money as college approaches. “The best advice came from the first seminar, where he told us how credit works,” she says. “He told us how at a young age you can mess up your credit, badly. Credit is really important, and I didn’t realize that before.”

![]()

More than anything, Bashir is excited that Banksgiving is preparing her to get the jump on her peers when it comes to opening a business, if she chooses to. “It’s 2017, and there’s kids out there making money at very young ages,” she notes.

According to Banks, the program is scaling quickly—almost too quickly for a man who works 140 miles away from the kids he’s mentoring. Things started modestly, with around 25 students attending his first class; in November, 75 students showed up, and Banks expects to see even more in this week’s class. He’s also fielding demands for more and more frequent programming.

Banksgiving, which is free to attend, is funded through donations. Banks is a bit tight-lipped about the future of Banksgiving, though he has said he’d like to turn the side project into a full-time gig by 2019. He also says he’s interfaced with city high-ups—including City Council members and local businesses—about expanding his program’s curriculum.

Already, Banks knows, he has to pick up the frequency of his seminars if he wants to make sure that any Philadelphia kid has access to his financial literacy courses—and gets the know-how to raise themselves out of their financial straits before they become adults.

“In September, one of the kids asked when the next session was, and I said January,” Banks says. “It sucked the air out of the room. No lie.”

Chris Banks