All is quiet around the little camp near the railroad tracks. Tall poplars whissh softly in the late summer breeze; the first rays of sunlight sparkle across the glass-encrusted ground; used syringes crunch underfoot. Three men in tank tops, already high, recline in broken lawn chairs and gaze at a hazy nothing. Two ageless women sit in silence inside the plywood-and-tarp shack. The others wait listlessly for heroin and release.

“GOOD MOOORNING! Buenos días!” A sturdy Latina marches in and shouts brightly at the drowsy men and women splayed out in the clearing. Hands on her hips, she commands the space like a tía whose nieces and nephews are about to be late to Sunday mass. A few sluggishly roll their heads toward the voice and let out an “ennh” in greeting.

The clearing is strewn with mirror shards placed just so: between the trunk and branch of a needle-stuck tree, nailed into the plywood wall of the shack, propped up on the stolen folding table. A blonde-dreadlocked woman leans over the mirror on the shack wall and empties a syringe of yellowish syrup into the base of her neck.

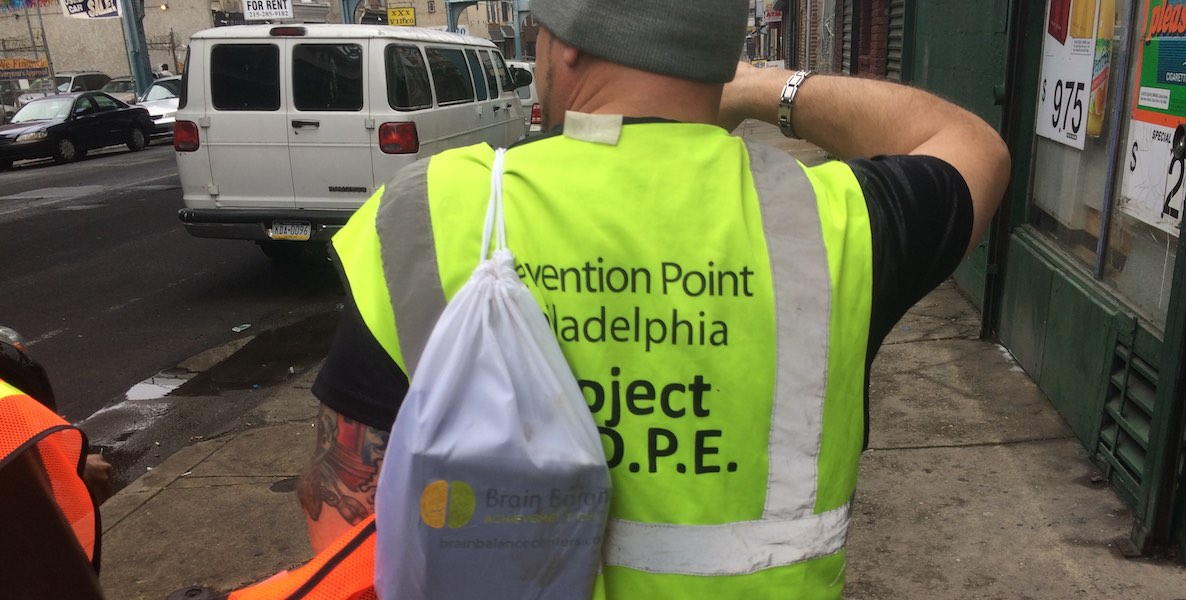

Charito is a registered nurse, but “out here there is no trauma unit, no maternity unit. You have to be your own hospital.” Someone was usually waiting for her to clean a raw wound from a fight, assault, or bad hit. She exchanged dirty needles for clean ones. She sprayed Narcan, an antidote drug, into the nostrils of overdose victims.

“Naaanciii! How are you doin’ today baby,” the tía yells her way. Getting no response, “I love you too!”

A few more people slowly fade back into reality and acknowledge the shrill presence in their home. They shuffle through the ankle-deep lawn of trash, grumbling about loud voices and bright sunlight and no-show government checks.

“YES HELLO good morning buenos días. How are you this morning? ¡Oye! On 2nd y Indiana there is water, food, detox, café, lo que tu necesites. ”

With that, Tía Charito wakes up the camp.

Every day until last August, Charito Morales had the same routine. She awoke at 4 am and headed toward the Conrail tracks that divide the North Philadelphia neighborhoods of Fairhill and Kensington. By 5 am she was down in El Campamento, Philly’s biggest heroin encampment, bringing food, clothing, and first aid to the open-air drug and sex market. She walked the six miles of tracks, counting the users, dealers, prostitutes, and pimps living in the gulch.

Charito is a registered nurse, but “out here there is no trauma unit, no maternity unit. You have to be your own hospital.” Someone was usually waiting for her to clean a raw wound from a fight, assault, or bad hit. She exchanged dirty needles for clean ones. She sprayed Narcan, an antidote drug, into the nostrils of overdose victims. She called the police about the corpses. Every so often she delivered a baby, already shaking violently with the tremors of undeserved withdrawal. She speaks with her hands. She calls everyone “corazón,” heart. And she educates as she goes, in a style that is safe for Charito and only Charito. Once she approached a heroin dealer, demanding, “Do you see how many childrens is trying to live here?”

![]() By 9:30 each morning, she finishes on the tracks and goes to her “real job.” She’s the outreach coordinator for Public Health Management Corporation, a nonprofit that manages several health centers in the region. She arrives at Mary Howard Health Center and greets some of the same faces she saw at dawn—she’d referred them to receive treatment and sent them on their way with a handful of SEPTA tokens. Besides working in the clinic, Charito makes home visits to impoverished and refugee families.

By 9:30 each morning, she finishes on the tracks and goes to her “real job.” She’s the outreach coordinator for Public Health Management Corporation, a nonprofit that manages several health centers in the region. She arrives at Mary Howard Health Center and greets some of the same faces she saw at dawn—she’d referred them to receive treatment and sent them on their way with a handful of SEPTA tokens. Besides working in the clinic, Charito makes home visits to impoverished and refugee families.

Some of her work is in a Neighborhood Advisory Committee T-shirt or a PHMC nametag, but some of it is completely incognito. Those days, she doesn’t reveal her employer—she’s just Charito, a community worker.

An expert in the social struggles of Kensington and Allegheny, fluent in Philly slang, and ready to defend any kid in the neighborhood, Charito seems the quintessential native North Philadelphian. But home is a small tribal village of indigenous Taínos, 1,562 miles away.

Charito was born to an Army mother and Navy Seal father in coastal Quebradillas, Puerto Rico. Their family moved from Quebradillas to New York, from New York to Connecticut. Charito’s parents sent her back to the island for summer vacation, where she fell in love with an island boy and, “not knowing nothing about sex,” became pregnant at fifteen. Her parents were outraged. Bent on keeping up appearances, they sent her to a military base in Georgia, where she cooked and cleaned for the officers as her stomach swelled. She gave birth to her first daughter in a bedroom with a single nurse.

Three months later, Charito escaped. Her lover mailed her a ticket back to Puerto Rico, and her nurse smuggled her to the airport. She returned to the tribe. They wouldn’t help her. She went to live with her daughter’s father, no longer the dreamy island boy she had known the year before. He began to scream at her for overcooked rice, to hit her for a wrong tone of voice. At 16, she became pregnant again. “I stay with one man forever,” she convinced herself. When he threw her down a staircase, her arm, knee and water broke. Her second daughter was born, four weeks premature, at the bottom of the stairs.

She found Eduardo in El Campamento. He told her, “You can’t help me, Charo. Maybe you can help some of these other guys.” And then he overdosed in front of her. He was 18 years old.

Her father finally allowed her to live in the village, separate from her peers as a warning and a disgrace. Her mother would shun her for another five years. She was allowed to finish high school, though, and graduated at age 18 with a 4.0 GPA and two young children. She began to take courses to become a special education teacher at a local college.

![]() Meanwhile, her younger brother Eduardo had joined a Latin gang and was hooked on opiates. Their parents moved the family back to Puerto Rico, but he didn’t change. When they heard about a beautiful rehab facility in Kensington, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA, with private rooms and a swimming pool, they sent him right away. They didn’t know that the neighborhood of Kensington was the heroin epicenter of the entire east coast of the United States. They didn’t know that so-called “recovery” houses existed to exploit addicted Puerto Rican youth. They didn’t know that their son was shoved into an empty building and stripped of his federal benefits. So when they discovered that he had disappeared, they sent Charito, the current disgrace of the family, to investigate.

Meanwhile, her younger brother Eduardo had joined a Latin gang and was hooked on opiates. Their parents moved the family back to Puerto Rico, but he didn’t change. When they heard about a beautiful rehab facility in Kensington, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA, with private rooms and a swimming pool, they sent him right away. They didn’t know that the neighborhood of Kensington was the heroin epicenter of the entire east coast of the United States. They didn’t know that so-called “recovery” houses existed to exploit addicted Puerto Rican youth. They didn’t know that their son was shoved into an empty building and stripped of his federal benefits. So when they discovered that he had disappeared, they sent Charito, the current disgrace of the family, to investigate.

She found Eduardo in El Campamento. Somehow, this was better than the recovery house. He was so ashamed that his sister would see him this way—dirty, desperate, crazy, covered in needle-welts and flies. He couldn’t face his parents. He knew how they had treated Charito when all she had done was bear a child. He told her, “You can’t help me, Charo. Maybe you can help some of these other guys.” And then he overdosed in front of her. He was 18 years old.

When they took her brother’s body away, Charito ached to go with him. As soon as she came to Philadelphia she had wanted to leave. Now she was trapped there—shunned by her family, mourning her brother, and alone with two young daughters. She waitressed for $3 an hour, and decorated their one-room apartment with trash-bag curtains. Toddlers on an air mattress, mamá on the floor. She found a job at a car parts factory, and tried to learn English when she could. Her brother’s words followed her. Maybe you can help some of these other guys.

A friend convinced her to apply for a Nursing degree from Drexel University. She worked in the factory all morning, took classes in the afternoon, and cleaned banks at night, with daughters along in a playpen and stroller. She became a registered nurse, and took graveyard shifts at St. Christopher’s hospital. Maybe you can help some of these other guys.

Charito worked in the factory all morning, took classes in the afternoon, and cleaned banks at night, with daughters along in a playpen and stroller. She became a registered nurse, and took graveyard shifts at St. Christopher’s hospital. Her brother’s words followed her. Maybe you can help some of these other guys.

One day she returned to the edge of the gulch. From a bridge over the tracks she could see the half-dead milling about in the shadows. Sliding on an avalanche of garbage and debris, she climbed down the near-vertical embankment into the depths of El Campamento. Immediately stepping into the wrong territory, she was threatened by screaming gang members and chased out of the gulch. She came back every day, intruding and insisting, until she knew every sign and whistle, until the warring gangs saw her presence as irritating but harmless.

![]() Last August, 20 years later, Charito intruded on the landscape of El Campamento for the last time. She walked her usual six miles, this time warning the remaining pockets of users about the bulldozers and backhoes that will raze their home the next day. She found a 56-year-old man named Jesús collapsed across the tracks, a few minutes shy of death by overdose. When Narcan revived him, she tried to guide him toward the hospital before the antidote wore off. “Ay, corazón, don’t fall over! We goin’ this way. Vente! You can’t come back down, they clearing this out.”

Last August, 20 years later, Charito intruded on the landscape of El Campamento for the last time. She walked her usual six miles, this time warning the remaining pockets of users about the bulldozers and backhoes that will raze their home the next day. She found a 56-year-old man named Jesús collapsed across the tracks, a few minutes shy of death by overdose. When Narcan revived him, she tried to guide him toward the hospital before the antidote wore off. “Ay, corazón, don’t fall over! We goin’ this way. Vente! You can’t come back down, they clearing this out.”

For the city of Philadelphia, this is the beginning of a comprehensive task force addressing the city’s decades-long struggle with opioid abuse. But for Charito Morales, this is the end of an era. The heroin pit where her brother died will be cleared out and fenced over in a few days. Makeshift homes, hookers’ mattresses, overdoses, murders, and wars will be replaced with evened gravel and cool steel brambles of barbed-wire fence.

Clean-up efforts are only pushing users further north and further east, away from the heart of a city that doesn’t want them. They will inevitably find new mirrors, prostitutes will lay new mats.

Wherever they go, Charito follows.