At first, the questions posed to a room of 20 Philadelphians of varying backgrounds last winter seemed innocuous: How many cars did your parents own when you were growing up? Did you live in a house or an apartment? Did you go to public or private school? But as the questions went on, they became more specific and vulnerable for the strangers in the room: Did your parents both go to college? Did you get gifts at the holidays? What type and quantity of food did you eat?

These were questions many of us might answer to only our closest friends. But the participants answered to each other, eventually putting themselves in a line from those who were wealthiest to those who were poorest. To Alisha Ebling, who comes from a white rural background, the exercise was telling: She found herself increasingly moving towards the poorer end of the line. But when it was all over, she saw that she was an outlier. Nearly all the white people were at the wealthy end, and most of the people of color were concentrated towards the poor end.

“It was a dramatic visual reminder of how ingrained class is with race,” says Ebling, a writer with a background in grassroots activism, “and how anytime we talk about class we must also include conversations on race. It also made us all cry.”

This exercise was the cornerstone of training the inaugural group of Philadelphians in the first-ever Giving Project, an initiative of Bread & Roses Community Fund that allows regular people to connect and donate to grassroots groups doing work for racial and economic justice. Modeled off a similar Seattle program, the idea was to upend the traditional philanthropy model: What if, the new idea went, instead of seeking big donations from wealthy donors, Bread & Roses could draw on many donations from ordinary people?

“We the people can, and must, recognize our power to transform our world. We cannot rely on money from foundations and corporations to do this work. We have to come together, be creative, take it back to basics, and remember that a small group of people can move mountains,” says Gonzales.

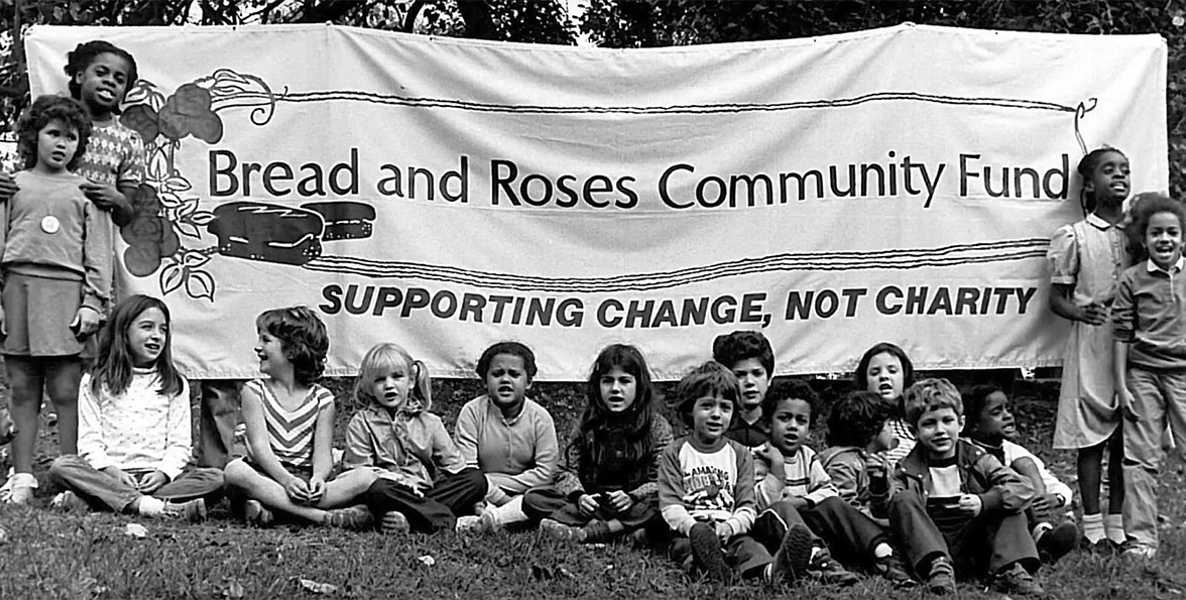

It was, in many ways, a turn back to the 4o-year-old organization’s roots. Founded in 1977, Bread & Roses rests on the idea that “the people in the best position to create real change are those who are most affected by injustice and inequality.” It was started by a small group of young people who wanted to support the movements in Philadelphia for Black Power, Civil Rights, and Women’s Rights. Members contributed relatively small amounts of money to a pot, held fundraisers to add to the collection, then came to a consensus to decide which organization would receive their funds.

Over the years, Bread & Roses has become a more traditional grantmaking organization: It raises money from big donors and awards big financial gifts. Still, it is unique among foundations in some ways: Bread & Roses gives grants only to small organizations (budgets less than $150,000) that are specifically doing grassroots social justice organizing and activism. By this they mean projects that address the root causes of a problem (mass incarceration, for example) rather than just its symptoms (helping those with felony records get jobs); that engage the communities most affected by the problem (poor communities of color); and that are led by or incorporate ideas from the affected community.

![]() Grantees tend to be local groups working on issues such as good schools, fewer prisons, better jobs, a safe environment and quality health care, including the grassroots umbrella partnership Philadelphia Coalition for Affordable Communities, which works to keep gentrifying neighborhoods affordable; the social justice arts nonprofit Spiral Q; the MOVE organization, which works for racial justice in Philadelphia and the paroling of the remaining members of the MOVE 9; and the Black Radical Organizing Collective.

Grantees tend to be local groups working on issues such as good schools, fewer prisons, better jobs, a safe environment and quality health care, including the grassroots umbrella partnership Philadelphia Coalition for Affordable Communities, which works to keep gentrifying neighborhoods affordable; the social justice arts nonprofit Spiral Q; the MOVE organization, which works for racial justice in Philadelphia and the paroling of the remaining members of the MOVE 9; and the Black Radical Organizing Collective.

This approach is a shift from the usual world of social justice granting, where the bulk of funding comes from governments, foundations, and corporations, often of a more conservative bent, that tend towards established groups with track records of success. Bread & Roses will take a risk on newer organizations, and those with less easily-defined outcomes—like Black Lives Matter—that are run by the people they’re trying to serve.

“What foundation, corporation, or government body is going to step up and pour money into Black Lives Matter?” asks Ebling. “Getting healthcare for undocumented individuals? They may feel comfortable putting money into a failing school, but not changing the systems that created that failing school. This is where Bread & Roses is different. Bread & Roses is the only funder in Philadelphia determined to create radical shifts in race and class inequality by funding those fighting for systems change, not just alleviation of a symptom.”

![]() The Giving Project puts Bread & Roses’ philosophy onto a model akin to crowdfunding. The first program launched last January, bringing together a group of Philadelphians of different races, classes, ages and sexual orientations for a 6-month education to gain a deeper understanding of race and racism, the impact of the growing wealth divide, and how to contribute to movements for racial and economic justice in the Philadelphia area. Recruited through grantee organizations, volunteers, and word of mouth, participants committed to raising money for the project from their friends and families as well as making a financial contribution themselves that was “personally meaningful” (i.e. it stretches your comfort zone without putting you in financial danger), but there was no minimum amount. The average gift was $3500, but the gifts ranged from $40 to $14,000, showing the true class diversity of the group.

The Giving Project puts Bread & Roses’ philosophy onto a model akin to crowdfunding. The first program launched last January, bringing together a group of Philadelphians of different races, classes, ages and sexual orientations for a 6-month education to gain a deeper understanding of race and racism, the impact of the growing wealth divide, and how to contribute to movements for racial and economic justice in the Philadelphia area. Recruited through grantee organizations, volunteers, and word of mouth, participants committed to raising money for the project from their friends and families as well as making a financial contribution themselves that was “personally meaningful” (i.e. it stretches your comfort zone without putting you in financial danger), but there was no minimum amount. The average gift was $3500, but the gifts ranged from $40 to $14,000, showing the true class diversity of the group.

The project takes Bread & Roses’ longtime commitment to “change not charity” in an exciting new direction: It says philanthropy isn’t just for rich people or fancy foundations; it is available to every citizen who cares about changing inequality and injustice. It might be a vital key to changing the model of philanthropy from detached charity to a collaboration available to all Philadelphians that also builds awareness of class inequality, racism, and privilege.

“We each got a cup filled with the same amount of water,” says Elicia Gonzales, the former Executive Director of GALAEI, who has been involved with B & R for years, including participating in the first B & R Giving Project. “We went around, one by one and said what our meaningful contribution would be and then poured the water into an empty pitcher. It symbolized that it didn’t matter the size of the gift, that every contribution went towards the overall goal.”

With this new model of grantmaking came unique emotional and logistical challenges.

“Part of the program was fundraising our communities,” adds another participant, Jules Burnstein, a 29 year-old math teacher who got involved with B & R through Resource Generation, an organization that brings together class-priveleged young adults. “We were encouraged to connect with family and friends and ask them to be a part of this project by giving money. I was so nervous to ask others for their support because I didn’t want to seem demanding or like I was asking too much. It was very moving to see my family and friends be so eager to participate.” The participants also received training on how to fundraise effectively.

Though the first Giving Project had a goal of $100,000, they more than doubled it, raising $210,000. Then, the group worked democratically to decide how to distribute the money.

Though the first Giving Project had a goal of $100,000, they more than doubled it, raising $210,000. Then, the group worked democratically to decide how to distribute the money. They interviewed organizations that had applied to Bread & Roses for funding and decided together on 15 grants of $10,000 each, 5 grants of $6,000 each, and an additional $9,000 in smaller grants. Grantees included ACT UP Philadelphia, ACTION United, and Youth United for Change. Check out the rest here. (The rest of the funds covered the cost of operating the Giving Project.)

![]() Bread & Roses plans to run the next Giving Project from January to June 2017, and at least one each following year and are currently accepting applications. B&R Executive Director Casey Cook says she hopes to see similar programs spread around the country.

Bread & Roses plans to run the next Giving Project from January to June 2017, and at least one each following year and are currently accepting applications. B&R Executive Director Casey Cook says she hopes to see similar programs spread around the country.

In a similar vein, Bread & Roses also recently organized a Change Ride, which again took a traditional fundraising structure—a “charity” bike ride—and turned it on its head. Instead of having participants bike around center city, participants in the Change Ride biked a route that exposed them to important locations and neighborhoods representing the work of Bread & Roses grantees. At each “info stop” participants learned about issues of injustice and the work B&R grantees are doing to change it—the work, in other words, their dollars would fund. They biked to the Spiral Q Arts Gallery on Lancaster Avenue in Mantua to hear about art as a tool of social justice; they biked to South Philadelphia to hear from women concerned about revitalization of homes in their neighborhood.

“Bread & Roses talks the talk and walks the walk,” says Gonzales. “We the people can, and must, recognize our power to transform our world. We cannot rely on money from foundations and corporations to do this work. We have to come together, be creative, take it back to basics, and remember that a small group of people can move mountains.”

Correction: A previous version of this story said Bread & Roses was founded in 1971; it was actually 1977. Also, an earlier version misstated the amount of money donated from the Giving Project; 15 percent of the total raised went to operate the program.

Header photo via Bread & Roses