If not for the bobcats and coyotes prowling around Arms Acres drug rehabilitation center in Hamlet, New York, Brandon Chastang might still be running with Percocets.

Chastang, a West Philadelphia native with almost four years of sobriety, struggled when he first arrived in 2017 at the facility, tucked away in an unfamiliar mountainous region in a house filled with strangers. After a week in detox and several days of lackluster sleep due to withdrawal, Chastang would listen to what he thought were the howls of dogs outside, and plan his escape from imprisonment.

“We are afraid to tell somebody we need help,” Chastang says. “Now. I’m sure that happens everywhere, right? But in the African-American and Black and Brown community, that’s what it is. If I tell you that I got to go get help somewhere, then I’m ‘weak’.”

Thirty days at Arms Acres made Chastang realize that he wasn’t alone. His story mirrored those told by the facility’s diverse array of clients, which included people experiencing homelessness, court-mandated persons, and even people with no inclination to stop using drugs. But that first week, he was set on getting out.

Then he realized: Those weren’t dogs.

“[Coyotes] make those sounds when they got food,” Chastang says, recalling the moment at rehab when he learned what he’d been hearing. “And there’s bobcats out there too? I’m not leaving. Because as soon as I leave, when I leave that door, it’s a long walk to civilization. I’m not going nowhere.”

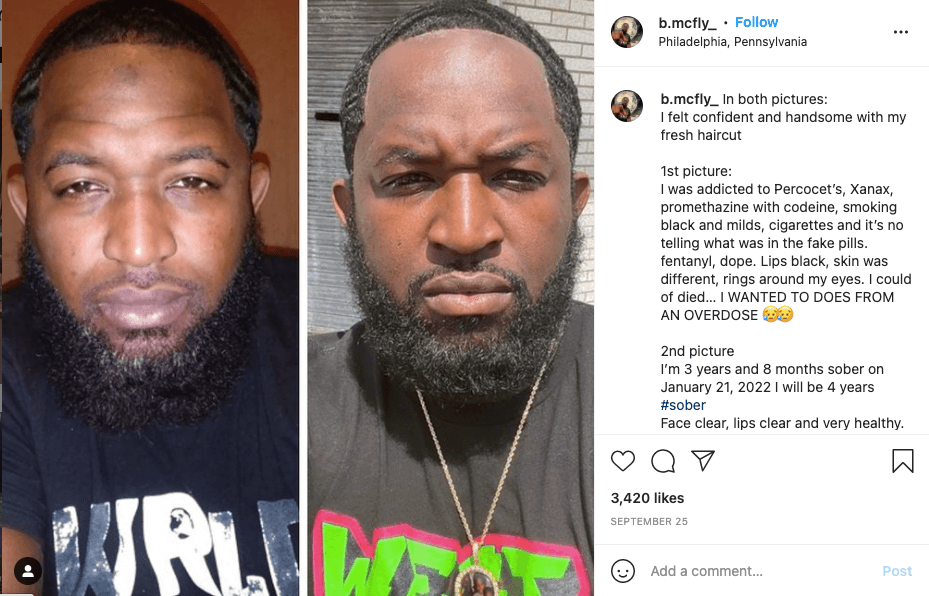

Brandon Chastang is publicly known as B. McFly, an acronym which stands for Being Motivated Comes from Loving Yourself and, in his own words, has illusions to everyone’s favorite time-traveling teenager from the 1980s. As a person with lived experience who hasn’t used drugs since 2018, Chastang now preaches sobriety, prevention, anti-violence, and love throughout Philadelphia. He’s a much sought-after influencer and public speaker in the city, whose social media presence and Self Inventory podcast bring words of hope and inspiration to thousands every day.

Yet unlike many post-rehab motivational speakers, Chastang has an innate ability to connect with African American audiences. In his own words, it’s his strong ties to urban culture—the way he speaks and dresses, for example—that portray a sincerity others can’t imitate. “[Urban culture] is more to us than just entertainment,” Chastang says.

Chastang speaks to an audience dismissed and traumatized by the decades-long War on Drugs. In 2020, during the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic, Black Philadelphians bore the brunt of the overdose crisis as fatalities rose 29 percent among the city’s African-American communities. Media and activist organizations centered their efforts on White neighborhoods like Kensington, while predominantly Black areas suffered in silence.

According to Chastang, in some African-American communities, asking for assistance is perceived as a shortcoming. “We are afraid to tell somebody we need help,” Chastang says. “Now. I’m sure that happens everywhere, right? But in the African-American and Black and Brown community, that’s what it is. If I tell you that I got to go get help somewhere, then I’m ‘weak’.”

So four years ago, in the mountainous region of upstate New York, Chastang developed his B. McFly persona and decided it would be something different. Around the time he accepted sobriety, Chastang also embraced transparency, becoming a motivational speaker— a sobriety motivator he calls himself. From experience, he says that people who use drugs always think they’re alone and that no one understands what they’re going through.

McFly could change that.

“It’s so hard to be transparent.”

Born to two teenage parents, both of whom struggled with drug use disorders of their own, Chastang’s was raised by his grandmother. His grandfather, who wasn’t his biological relative, physically and emotionally abused him, setting the stage for the lifelong trauma that would lead to his eventual drug use. As Chastang says, he grew up in an aggressive environment.

Still, he managed some early success. Growing up on 60th and Master streets in West Philadelphia, Chastang is quick to note he attended all of the same schools as Wilt Chamberlain, Will Smith, and the city’s own NASA astronaut Guion Bluford. In 2004, he graduated from Lincoln University, one of the country’s first degree-granting historically Black colleges and universities. The following month he was shot, and a doctor gave him a script for Percocet to ease the pain.

Brandon Chastang ran with that script for another 15 years.

“[It was] tumultuous,” Aocean Clarke, the mother of Chastang’s two youngest children, who’s now a teacher in New York, recalls. “He would call or ask for money, steal my money. I remember our son had his first birthday. He got a bunch of money. He took all the money. DWIs, a lot of lying, a lot of infidelity.”

Through it all, however, Clarke stood by Chastang. Even though he made many bad decisions, she says she knew it wasn’t his fault; it was the drugs. Clarke now sees a man healing from his trauma and doing everything he can to help others. Chastang will go to extremes, she says, driving people to rehab when they need it or spending significant amounts of time on the phone with a person in crisis. “He’s putting his everything into paying it forward,” Clarke says.

For 15 years, Brandon Chastang found drugs helped his physical pain and dulled his emotional trauma. The mental anguish which he suffered in silence found relief with every Percocet pill he took. But with the reassurance of every pill came the need for more until the silence would no longer hold.

“It’s so hard to be transparent,” Chastang says. “We are afraid to tell somebody we’re going through something because we’re afraid that they’re going to use it against us. But a person like me that’s transparent—and there’s other people out there, I’m sure there is, that can do the same thing that I’m doing—I don’t know, man. Like, that’s the only way.”

Public speaking and social media became tools for Chastang to tell his story. As B. McFly, Chastang told anyone who would listen that he used Percocets for 15 years, was a deadbeat father, a criminal, a womanizer, and, in his own words, a coward. Brandon Chastang showed his weakness so he could help others.

Highlighting voices and experiences

Over the past few years, his Instagram feed, with pre-written skits about raising children from prison and dying on the streets, amassed an astounding 93,000 followers and counting. B. McFly now hosts “Self Inventory,” a 40- to 60-minute podcast he launched with the assistance of Studio D, a Philadelphia-based podcast production company. “Self Inventory,” named for the psychological questionnaires that ask people to look inward and reevaluate their beliefs and values, focuses on contemporary social issues affecting the city.

The show highlights Chastang’s open, easygoing persona using a one-on-one interview format, interspersed with an occasional monologue for personal reflection. Recent guests included Police Captain Matthew Gillespie, Fah da Barber, the South Philly legend who cuts hair for The Roots, and Shayna Robinson-Owens, an area high school student who received over $1 million in scholarships to 25 different universities. Last March, in a 40-minute special episode with no guest, Chastang told his own story of drug use, sobriety, and adopting the B. McFly persona.

“Highlighting voices with lived experience like Brandon, puts a face of humanity to an epidemic that can be dehumanizing,” Dr. H. Jean Wright II, deputy commissioner of DBHIDS, says. “It is especially important to the African-American community to show these faces and highlight these voices so that individuals suffering with addiction can realize there is a community of recovery that looks like them and has similar life experiences.”

Chastang also shares his truth throughout Philadelphia at schools, nonprofit organizations, and public-facing government agencies like the Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services.

“Highlighting voices with lived experience like Brandon, puts a face of humanity to an epidemic that can be dehumanizing,” Dr. H. Jean Wright II, deputy commissioner of DBHIDS, says. “It is especially important to the African-American community to show these faces and highlight these voices so that individuals suffering with addiction can realize there is a community of recovery that looks like them and has similar life experiences.”

For example, in a recent Instagram video, B. McFly stood outside the Northeast Treatment Center’s North 5th St. location with a woman wearing a black protective mask. Earlier that day, Chastang staged an intervention for her cousin at the family’s request, a process which ended with the young man choosing to enter a rehabilitation facility. “We saved another life,” B. McFly exclaims, as the woman on camera prompts others to reach out to him if they have loved ones in need.

“It’s very important to have his voice as well as mine in the community,” Suleiman Hassan says. “People are contacting him. People are contacting me. We’re taking people into rehab all the time.”

Hassan, who has seven years of sobriety himself, is the CEO of Soldiers for Recovery, a Philly nonprofit that goes into neighborhoods offering direct support to people using drugs. He works closely with Chastang, and like him, shares his story openly with the public. Later this year, he plans to launch the No Addict Left Behind program to help even more people find recovery.

“It’s important because of the statistics and the numbers of African Americans that are overdosing young as 14, young as 13, with the fentanyl epidemic that’s going on out here,” says Hassan. “A lot of the younger generations—they listen to B. McFly, they listen to Soldiers for Recovery as well. So it’s very important for his voice to be out here on Instagram as well as other platforms.”

For help with drug or alcohol use, contact Philadelphia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services here or reach out to Community Behavioral Health at 888-545-2600. The Philadelphia Department of Public Health, in partnership with harm reduction organizations SOL Collective and NEXT Distro also offer free, confidential access to the overdose reversal drug naloxone, and fentanyl test strips, by mail. For more information go to nextdistro.org/philly—or nextdistro.org/phillyfentstrips.

Photo courtesy of Brandon Chastang, aka "B.McFly"