For decades, Kathleen Bast, a longtime reading specialist, literacy supervisor and now a principal in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, taught students to read in the same way students are taught in many parts of the country, including Philadelphia.

She used what’s known as the “Whole Language” approach, which exposes children to as much of the printed word as possible, with the idea that the more they see it and the more they write it, the better they will get, picking up reading naturally as they go.

In what are known as the “reading wars”—a pitched debate among educators about the best way to teach reading—Bast firmly believed this approach was best.

MORE ON READING AND LITERACY

Bast happened to be out on medical leave in 2016 when Bethlehem’s new chief academic officer, Jack Silva, decided to upend everything she had known. He implemented district-wide a literacy program called the “Science of Reading”—essentially coming down on the other side of the reading war. He asked teachers to review the research and poke holes in it, if they could.

Bast became a convert. “I had no choice but to accept it,” she says. “It was very simply that I was presented with an alternative point of view.”

In Philadelphia, in the last pre-pandemic school year, only 45 percent of the school district’s kindergarten through second grade students were reading at grade level. And only one in three were considered proficient or advanced by the end of third grade—a harbinger of struggles in the rest of their school years.

In Bethlehem, similarly, students had struggled to learn reading for years. And both districts lost ground in the pandemic. But pre-Covid-19, the district was starting to tell a different story. In 2015, 51 percent of Bethlehem’s incoming kindergartners read at their grade level in the fall. By June, 71 percent were reading at grade level. Better, but not great; three in 10 students were still behind.

Then, in the fall of 2016, the district implemented the Science of Reading, known as Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS), a comprehensive program developed by two veteran literacy experts, Louisa Moats and Carol Tolman, both PhDs. And the change was dramatic. By the following June, 88 percent of the district’s kindergarteners were reading at grade level, up from 46 percent when school started in September, and up from 71 percent the prior year. That progress continued over the next several years.

“Students are feeling successful,” says Bast, who is principal of Calypso Elementary School, where two-thirds of the children qualify for free lunches. “Behavior incidents are down; unsuccessful students are going to be the ones who act out because they are not able to learn. It also changed for the staff. We got into this profession to help kids and it was frustrating when the same kids came up every year [needing remedial help]. Now we’re not having those same conversations about the same kids four years in a row.”

Learning by listening

The Science of Reading posits that learning to read is as much an auditory process as a visual one. Just as we learn to speak by hearing those around us, we also learn to read by listening. The key is to connect the sounds we hear with those squiggles on paper known as letters, what academics refer to as phonemic awareness. From there, it’s a matter of decoding words and linking what we hear and see with our knowledge of the world.

The phonics Bethlehem’s students learn is different from the letter-of-the-day approach. No one’s running through the alphabet, starting with an “A is for apple” poster in September.

Instead, students may spend a full class period studying the trifecta of sounds in cat, plus experimenting with what happens when there’s a p instead of a c in the beginning, or maybe a p instead of t at the end. To make those connections, they feel the vibrations in their throats—they pay attention to where their tongues and teeth are. They write the words on their own individual white boards divided into blocks for each sound—the explosive “c,” the “a” and, of course, the “t.”

“I feel like I owe letters of apologies to decades of kids, because what I was teaching them wasn’t right. I didn’t know any better,” Bast says. “I was doing the best I could with what I knew.” But still. “I’m still not over it.”

And so it goes for the 44 sounds that make up the English language—with the most used sounds, such as p and t coming up early, even though they are closer to the end of the alphabet. With this method, there are hand motions for kinetic learners and a certain sing-songy repetitiveness to fast-paced classroom drills, which are both comforting and easy to master so students build confidence as they go.

In addition to Bethlehem, districts from New Mexico to Mississippi have adopted—and found success—with the Science of Reading.

In Philadelphia, the Science of Reading has been on the horizon since about 2015, when the district adopted a stronger focus on early literacy, says Dr. Nyshawana Francis-Thompson, deputy chief of curriculum and instruction. And across the district, some teachers are already putting the concepts into practice. But Francis-Thompson says adoption has been spotty and largely dependent on the practices of individual teachers, many of whom had been teaching reading for decades using the whole language approach.

For this school year, the district adopted it as one of its main literacy approaches. Next year, Francis-Thompson says Philly schools will continue to implement the Science of Reading in K-3 classes, in addition to curriculum that “will be rooted in culturally sustaining practices” beyond this one method.

But she won’t promise when Philadelphia will see a measurable increase in performance. “It’s a whole shift in how we approach reading,” she says. “It takes time to shift teacher practice and therefore it takes time to shift student performance. It won’t happen overnight.”

Unlike the soft roll-out, with low expectations, that we’re seeing in Philadelphia, Bethlehem’s approach to adopting a new literacy curriculum was laser-focused. And yes, it was top-down. But Bethlehem’s approach was more than memos issued from on high. Silva, the chief academic officer, had to address the power dynamic in schools and the mixed feelings of faculty understandably cynical about “flavor-of-the month” initiatives.

“There’s only a finite amount of resources and a finite amount of time,” Silva says. “I was comfortable with saying this is the single most important thing in the Bethlehem area school district and our budgets and our schedules and our outlooks and our reporting and our communication will reflect it.

“Our kids need it, and we need it,” he says. “You have to start with the why. And in terms of reading, you have to ask the question, is it acceptable or unacceptable to keep having—year after year—half your kids leaving third grade [reading below grade level]?”

A heavy lift

Upending the way reading has been taught for decades has been—and continues to be—a heavy lift. Before the program was rolled out to teachers, Silva insisted that the principals spend a whole year learning the science and undergoing the same training classroom teachers would later receive.

“I know from being a principal and from working very closely with principals that nothing really happens with any fidelity or intensity without the principal being behind it and making it part of their regular conversations with teachers,” he says. “So, you skip over principals at your own peril, because they are the ones who are going to be largely responsible for it being embedded.”

As Bethlehem’s teachers began their professional development training in the “Science of Reading,” the principals took the classes again—side by side with the teachers. When there’s turnover and new teachers come on board, Bast and the other principals train again—and again. The district also employs job coaches embedded in the schools who help the teachers in a way intended to not feel threatening or punitive. “It is that modeling and constant walking with them instead of telling them what to do,” Bast says.

In Philadelphia, in the last pre-pandemic school year, only 45 percent of the school district’s kindergarten through second grade students were reading at grade level. And only one in three were considered proficient or advanced by the end of third grade—a harbinger of struggles in the rest of their school years.

No matter how the teachers may have felt at first—and there were some grumblers—they had to get with the program. “This is where it’s going,” Bast says she told her teachers when it was time to implement the program in her school. “You either get on the bus or get under it.” Now in Bethlehem, any elementary teachers who want to get hired need to be familiar with, and agreeable to teaching, the “Science of Reading” methodology. If they aren’t, they won’t teach in Bethlehem, Silva says.

As a reading specialist, Bast had spent years in unsuccessful struggles to catch up children who had fallen behind. “An eighth-grade boy who can’t read—that is an unmotivated child,” she says. “All the instruction I was giving them, and I wasn’t making a difference. They enjoyed our time together, but they weren’t becoming better readers.”

Once she saw the results of the Science of Reading, Bast says her own first reaction was guilt. “I feel like I owe letters of apologies to decades of kids, because what I was teaching them wasn’t right. I didn’t know any better,” she says. “I was doing the best I could with what I knew.” But still. “I’m still not over it.”

Other educators felt the same way, so the district and principals coined a phrase that seemed to help: “When we know better, we do better.” No blame, no shame.

Learning to read, reading to learn

The debate over how to teach reading is by no means settled, but as fierce as the reading wars are, everyone agrees on one key point: For students to be successful in school and in life, they must be reading on grade level by the end of third grade. In the early grades, students learn to read; from fourth grade on, they read to learn.

Nearly 90 percent of high school dropouts were struggling readers in third grade, according to research by the Annie E. Casey Foundation. Even the fourth-grade written curriculum is too challenging for third graders who enter fourth grade reading below grade level. That’s why in 2015, Philadelphia launched its Read By 4th initiative, a citywide effort to get kids reading at grade level. But unlike in Bethlehem, that effort has not yet seen the kinds of results that show real progress is being made—something even more pressing now given the learning losses of the last year.

If public education has a mission of equipping a nation’s citizens for success and participation, then what happens in the classroom is more than drills at “a perky pace.” Reading on grade level by grade three matters when it comes to racial equity and social mobility. “The most important thing we can do is teach our kids to read,” Martin-Medina says. “It’s equity work.”

Francis-Thompson, who has been Philadelphia’s deputy chief of curriculum and instruction since February, says she became a convert to Science of Reading as a special education teacher. She noticed that many of her students had a knowledge gap—they didn’t understand the connection between the sounds of letters and the letters themselves. That put them behind in reading and may have led to them being assigned to special education classes. When she applied the Science of Reading methods, she saw improvements among those students as each month passed and began to wonder why they had missed that instruction while in their regular classrooms.

One barrier to widespread adoption is, until recently, the dearth of training programs that offer the Science of Reading—which means, Francis-Thompson points out, that school districts have to take on the expense and time to train teachers themselves. (That is changing, at least somewhat. Temple, St. Joe’s, Drexel and Acadia all offer exposure to the Science of Reading to education students.)

Still, nearly six years after the method first surfaced in the Philly district, teachers are mostly left to decide for themselves how to teach reading—in the way that has left more children behind than not, or the way that even the administrator in charge of curriculum has come to see as the route to success. It’s true, as evidenced by Bethlehem, that the lift of a system-wide change is heavy and costly. But as Bethlehem has also evidenced, it might be worth it.

Setting expectations

For Maria Gil, a mother of five in Bethlehem, Pa., the difference in the teaching methods is clear in her own home. Her younger two school-aged children—sons in 4th and 5th grades—read more confidently than her older children, daughters in 8th and 11th grades. Gil’s daughters missed out on this program; her sons did not. It was that simple. And that complex. “I saw the difference,” she says.

Gil’s sons attend Donegan Elementary School, as did her daughters. Located between Lehigh University and Bethlehem Steel’s former plant, the school’s 428 students are primarily Latino and 89 percent qualify for free or reduced school lunches.

“What Bethlehem has done so well is set expectations for the principals,” says Donegan’s principal, Erin Martin-Medina, who says that “part of being a leader is being the lead learner. If I’m not engaged, I’m not going to be able to provide feedback to the staff. There are high expectations placed on us, but there is also a high level of support. People are seeing the results, and of course, we’re going to move forward.”

If public education has a mission of equipping a nation’s citizens for success and participation, then, Martin-Medina says, what happens in the classroom is more than drills at “a perky pace.” Reading on grade level by grade three matters when it comes to racial equity and social mobility. “The most important thing we can do is teach our kids to read,” she says. “It’s equity work.”

Gil appreciates how the schools have reached out to the parents to provide them more training on how to help their children. Gil, a native Spanish speaker, has also learned about phonics—the sounds and the long vowels and how some consonants don’t have a sound.

“With my daughters, I feel very sad because I didn’t know how to help them,” she says. “They had problems with their comprehension.” To this day, although they can read, they simply aren’t as confident as they could have been. When they read, she said, it’s more a chore than a joy. As for her sons, “they are more comfortable—more sure of what they are reading. They have more fluency.”

“When they are reading,” she says, “they enjoy it.”

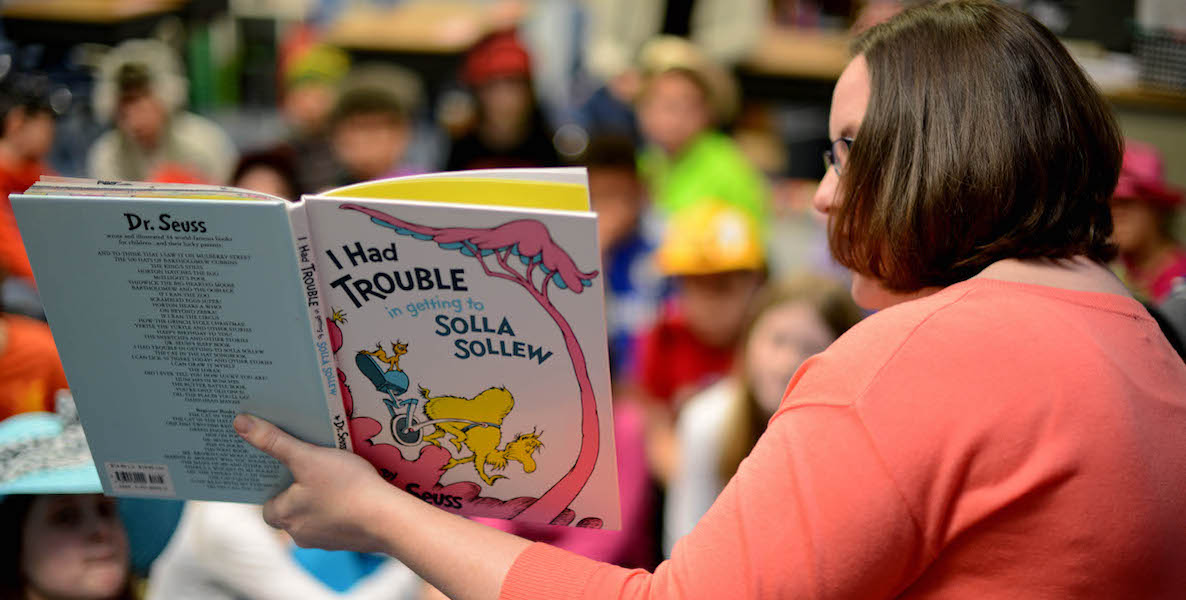

Photo by Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash