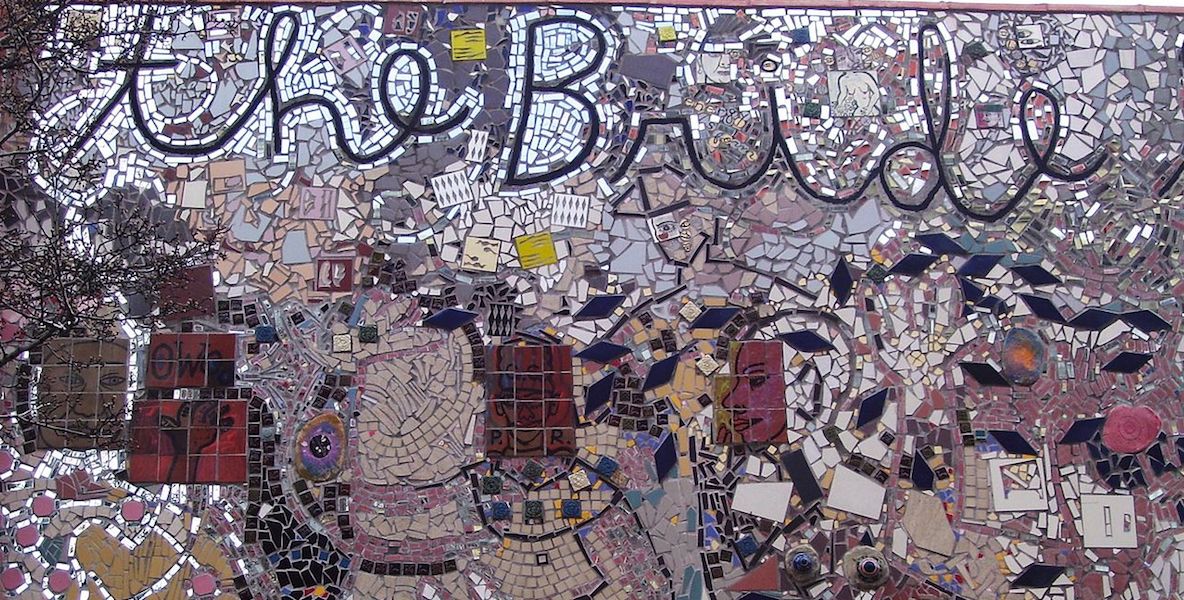

This Friday, the full panel of Philadelphia’s Historical Commission will make its decision on a fascinating “would you rather” arts question: Is it more important to preserve Isaiah Zagar’s iconic “Skin of the Bride” mosaic that covers the Painted Bride Arts Center building at 230 Vine Street, or to allow the Painted Bride the right to decide its own future? Which Philadelphia art legend should have its desires met? And, what does it all mean for the future of public and accessible art in Philadelphia?

At issue is the Bride’s intention to sell its Zagar-adorned building to fund its idea of what an alternative arts organization should be in the 21st Century—namely a borderless entity, bringing its performances to neighborhoods across the city. The working theory is that, without a Historical Commission designation, the Bride can sell its building at a higher price.

The hitch? The mosaics’ fate would rest at the mercy of the new buyer. With the designation, the mosaics are saved, but potential buyers may be scared off and the Bride may have to sell at a lower price, potentially putting its future vision on hold. Further, without the sale, the Bride might have to remain stuck in its building, directing funds towards maintenance, rather than creative projects.

The controversy started last March when Bride staff, after announcing plans to sell the building and take their work on the road, were notified that Zagar’s representative had applied for the Painted Bride building to receive historic designation. The move by Emily Smith, the executive director of the Philadelphia’s Magic Gardens, (Zagar’s labyrinthine, tour de force art environment at 1020 South street), blindsided the Bride’s board and staff and effectively halted its plans to move forward with the building’s sale.

In attendance at Friday’s hearing will be, among others, 79-year-old Zagar; Painted Bride executive director Laurel Raczka, who has worked at the Bride for the last 25 years; and Smith, the individual tasked with safeguarding Zagar’s work. It is the final showdown in a debate that has embroiled longtime friends, fellow artists and observers in a emotion-filled planning struggle that embodies the state of the arts in Philadelphia today.

“It sounds hokey,” says Smith a few days before the meeting, “But we want everything to be as good as it can be. I’m not trying to destroy the Painted Bride as an organization, but my job, as it’s written, is to preserve [Zagar’s] work. There’s nothing about this process that’s triumphant or a feel-good situation.”

Witness cultural history being decidedDo Something

If the designation is granted, it comes with certain protections that would guarantee Zagar’s work would not suffer the same fate as his 100-foot-long “The Garden of Earthly Delights” mosaic at the former Society Hill Playhouse. The Playhouse was bought by developer Toll Brothers, and the venue and Zagar’s mural were completely demolished in 2016 to make way for new condos.

“The Playhouse was a tough loss for us,” says Smith, who describes the unsuccessful process to persuade Toll Brothers to save the mosaic murals. Smith’s not full of hope that a buyer of the Bride space would save those murals either. “If you consider the reality of what’s happening in Philadelphia and where the building is located, it’s pretty clear,” says Smith. “People don’t want a mosaic to take care of on their property. If you’re not being forced to consider it, it’s pretty easy to tear it down.”

Can some kind of common ground or compromise be found, between preserving our cultural heritage and expanding that culture to every audience?

The Bride was the site of Zagar’s first fully-embellished building in Philadelphia, and the first time he worked in the full-scale manner that he’s known for today. The mosaic goes from sidewalk to roof, on all five facades of the building. “What’s really special,” adds Smith, “is that it directly references so many different artists and moments in alternative arts culture in Philadelphia. The history of the Painted Bride is written on the walls of the mosaic.”

Moving the mosaics is logistically possible, but cost prohibitive. Zagar adhered pieces directly onto the wall so the mural becomes a part of the building’s architecture. To move the art, one would have to move the entire wall. Another wrinkle in this preservation dilemma comes in the form of reports from a structural engineer, hired by the Bride, who was concerned about the state of the building, and the mosaic. According to Raczka, one report said that “50 percent of the mosaic [along Vine Street] is delaminated, which means it is separating from the building. The wall by the entrance is one hundred percent delaminated and is an immediate safety concern.” Caution tape now encircles the building’s periphery.

Smith, too, has seen the report, but is not alarmed at its findings.

Stories about the arts by Sarah Jordan Read More

“They may seem dramatic to you,” Smith says, “but they’re pretty standard for what we are all working on. There’s water behind mosaics, but like any building, it needs upkeep. Nothing in those reports shocked us. We have a preservation team and all of that stuff is fixable.” Magic Gardens wants to provide care and maintenance of the mural for free.

Not in dispute is that the “Zagar method” employed a type of mastic adhesion typically used for interiors and many of the indoor tiles are not meant for outdoor climates. Still, Zagar insists the the resulting problem areas can be effectively addressed.

“It is one of the most important pieces of art I’ve ever done,” says Zagar about ”Skin of the Bride.” “Everything was a struggle about it—the complexity of that much space to cover. I had to fund it myself. It was a real challenge, but it was my way of expressing my thanks to the Bride for what it had given me.”

The Bride opened in 1969, as an alternative arts performance space and has a long and respected legacy of creativity and civic engagement, centered around its beloved space at 230 Vine. Raczka says that building is almost paid off, and that the Bride is in good financial shape generally. But its mission no longer supports staying still—and the organization can not afford to both maintain the building, with needed upgrades to its HVAC, roof and electrical systems, and commit to its reinvention with the time, energy and funding to make it work. After one final season on Vine Street, granting its space rent-free to 25 artists and commissioning two original dance performances, the Bride hopes to start its citywide programming in 2019.

“We feel our role is bringing work to different neighborhoods where they don’t necessarily have access, and access being time, money and a level of comfort in coming to institutions,” says Raczka.

“I know this organization,” says Raczka. “I’ve been through highs and lows with it. I’m also connected to the larger issues in the field nationally, so I think about this stuff all the time.This is not just some kind of ‘I give up,’ strategy. We really saw this as forward thinking and we still do. The Painted Bride started as an alternative arts space to give voice to underrepresented artists and we were able to create a really diverse artist and audience base. Now, in 2018, it’s not enough. The issues are equity and access. So how do you get culture beyond Center City?”

Raczka cites a November 2014 study by the University of Pennsylvania Social Impact of the Arts Project and The Reinvestment Fund, that reports: “‘Advantaged’ neighborhoods account for only 37 percent of the city’s population but receive 89 percent of the arts and culture grants and 96 percent of the funding from philanthropies. ‘Disadvantaged’ neighborhoods receive 5 percent of the grants and 1 percent of the funding.”

She and the board say this is all wrong and the Bride needs radical change to engage with those communities that are thirsty for relevant arts. “We feel our role is bringing work to different neighborhoods where they don’t necessarily have access, and access being time, money and a level of comfort in coming to institutions,” says Raczka. “Real change is going to happen in creating these safe places for people to interact across all of these issues. We know that art is a powerful tool to bring people together and to have an impact on lives.”

Cities are fluid and in a constant state of reinvention. But in Philly, that reinvention can often mean a loss of its unique charms and character—think about the planned high rise atop Jeweler’s Row, the demolition of old iconic churches, the buildings going up that block popular murals. Judicious city planning could mitigate these losses. “I could be wrong,” says Smith, “But my personal approach to life is you don’t need to destroy something to continue to move forward.”

On the other hand, it is not the Bride’s mission to maintain a museum of Zagar’s work—that exists already, at 10th and South. And Raczka says the organization wants to look forward, not backwards. Shouldn’t the Bride control its own future? “It’s time to rethink and challenge all of our previous assumptions,” says Raczka. “All industries are shifting right now. It’s a totally different world so why wouldn’t arts shift as well?”

Can some kind of common ground or compromise be found, between preserving our cultural heritage and expanding that culture to every audience? That is the real conundrum the Historical Commission faces on Friday.