Because of the pandemic, the benefits of widespread mail-in voting have understandably been framed by officials in terms of the health benefits of voting from home. But there’s also an important election security benefit that was underscored this week by the news of a seriously old-school ballot box stuffing scandal involving a judge of elections.

On Thursday, Mensah Dean reported that Domenick DeMuro, a former judge of elections and Democratic committee person in South Philadelphia pleaded guilty to accepting $2,500 in bribes from an as-yet-unnamed political consultant to cast extra votes for three Court of Common Pleas candidates between 2014 and 2016. U.S. Attorney William McSwain announced the charges on Thursday in a video message.

![]() “DeMuro fraudulently stuffed the ballot box by literally standing in a voting booth and voting over and over, as fast as he could, while he thought the coast was clear,”…McSwain said.

“DeMuro fraudulently stuffed the ballot box by literally standing in a voting booth and voting over and over, as fast as he could, while he thought the coast was clear,”…McSwain said.

Reading about how DeMuro went about this, one takeaway that comes to mind is how hard it would be logistically to cast a similar number of fraudulent votes using mail-in ballots.

In May 2014, DeMuro inflated vote totals by adding 27 fraudulent ballots in the primary election, 40 votes in May 2015, and 46 in 2016, according to court documents outlining the scheme and the charges against him.”

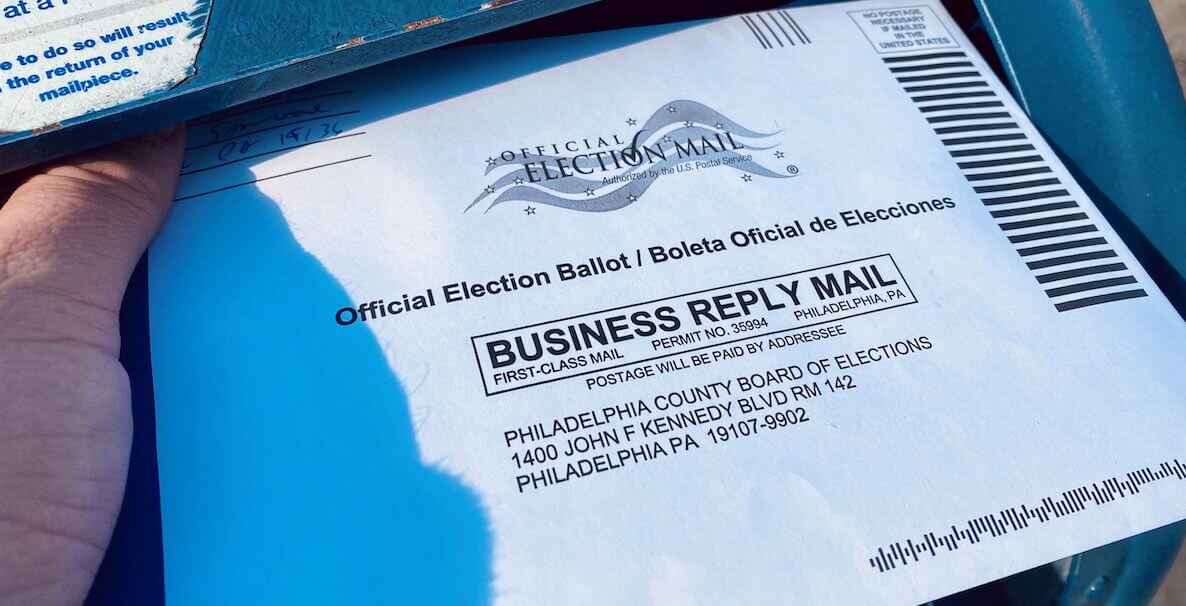

With each mail-in ballot tied to an individual, and sent to a home address, voter fraud becomes much more difficult. As The New York Times editorial board notes, “States that use vote-by-mail have encountered essentially zero fraud: Oregon, the pioneer in this area, has sent out more than 100 million mail-in ballots since 2000, and has documented only about a dozen cases of proven fraud.”

Voter fraud of any kind is rare, but some methods of voting are more secure than others, and a lot of it comes down to the details of implementation. As The New York Times editorial board notes, “states that use vote-by-mail have encountered essentially zero fraud: Oregon, the pioneer in this area, has sent out more than 100 million mail-in ballots since 2000, and has documented only about a dozen cases of proven fraud.”

Philadelphia’s in-person election administration has had its fair share of problems as well, with challenges recruiting and training poll workers (who are technically elected in division-level elections every 4 years, next up in 2021), and with monitoring for misconduct like campaigning from the table or actual fraud, and this is one of several good reasons to prefer a long-term shift to mostly-mail elections in Philadelphia, while keeping a smaller number of in-person voting options.

Jon Geeting is the director of engagement at Philadelphia 3.0, a political action committee that supports efforts to reform and modernize City Hall. This is part of a series of articles running on both The Citizen and 3.0’s blog.

Header photo courtesy phila.gov