“How do you use a dictionary?”

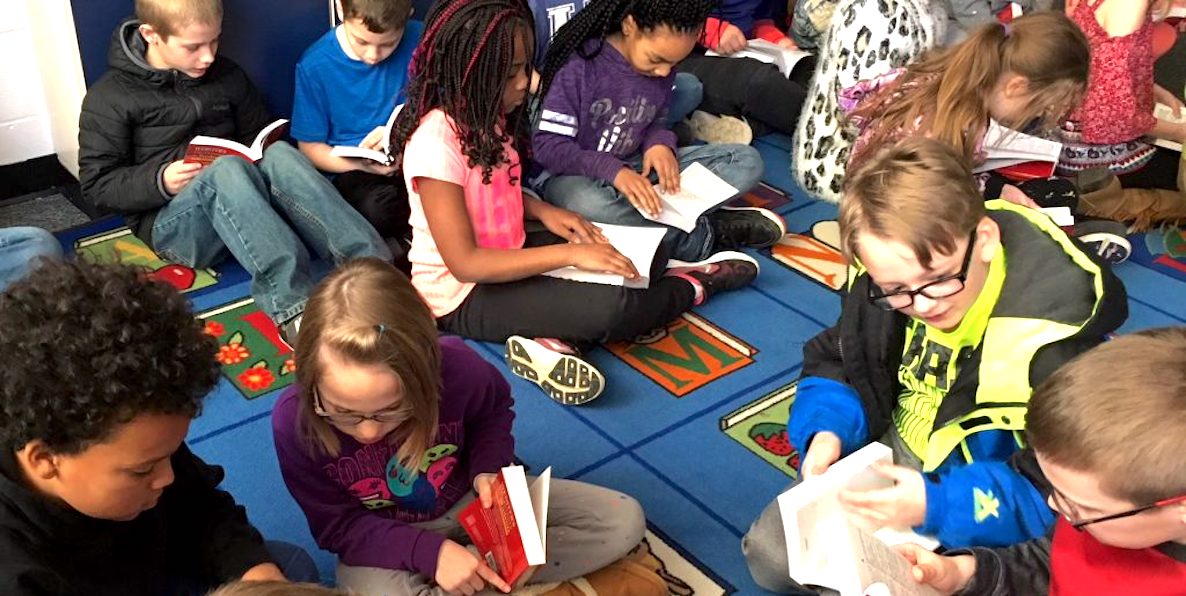

Kim McKay asked this question on a recent Friday afternoon, as she handed out new copies of A Student’s Dictionary to two classrooms full of third grade students at Spring Garden Elementary School. Hands in the classroom immediately shot up.

“When you don’t know how to spell a word,” said a boy sitting in the middle of the classroom.

“When you don’t know what a word means,” chimed in another girl.

![]() McKay, a member of the Philadelphia Ethical Society, was making her annual visit to the school on behalf of The Dictionary Project, a Charleston, South Carolina-based nonprofit with a mission to provide every third grader in the United States with a dictionary. Since its inception in 1995, volunteers around the world have distributed 18 million dictionaries to students in the U.S. and 15-plus other countries around the world.

McKay, a member of the Philadelphia Ethical Society, was making her annual visit to the school on behalf of The Dictionary Project, a Charleston, South Carolina-based nonprofit with a mission to provide every third grader in the United States with a dictionary. Since its inception in 1995, volunteers around the world have distributed 18 million dictionaries to students in the U.S. and 15-plus other countries around the world.

Through her involvement in The Philadelphia Ethical Society, an organization founded in 1885 to “create meaningfulness in the world and treat others with respect,” McKay has been carrying out the work of The Dictionary Project for four years, visiting Stephanie Perna’s third grade class each time.

The Dictionary Project’s origins date back to 1992, when Annie Plummer, a housekeeper in Savannah, Georgia, gave 50 dictionaries to students in a nearby school. In her lifetime—Plummer died in 1999—she raised enough money through apparel sales, a Dictionary Walkathon, and the help of local churches and community centers to buy 17,000 dictionaries for Savannah children. Her work was expanded by other volunteers and The Dictionary Project officially became a nonprofit in 1995.

The Dictionary Project has distributed 18 million dictionaries to students in the U.S. and 15-plus other countries around the world.

Third grade is a key year to get the tomes in the hands of students: Educators, as the Project’s website says, consider that year “the dividing line between learning to read and reading to learn.” By fourth grade, if students struggle with reading, they will likely have trouble comprehending information in classes beyond just English, including history, science and math. That’s why the City and Free Library launched Read by 4th, a citywide effort to get every student reading at grade level by the end of 3rd grade.

Tech enthusiasts might see dictionaries as obsolete, but McKay disagrees. Not ![]() every student has access to the internet, she points out. And with a dictionary, students can derive a real sense of accomplishment when they find a word they’re looking for. Plus, simply flipping pages to search for a definition exposes students to new words they may not have known. Like, for example, plethora, McKay’s favorite word, which she asked the students to look up.

every student has access to the internet, she points out. And with a dictionary, students can derive a real sense of accomplishment when they find a word they’re looking for. Plus, simply flipping pages to search for a definition exposes students to new words they may not have known. Like, for example, plethora, McKay’s favorite word, which she asked the students to look up.

She showed the students how to navigate the pages of the dictionary by using alphabetical order and paying attention to the words at the top corner of each page. Their new dictionaries also had the alphabet listed on the back cover, in case the students forgot, say, if “m” came before or after “n.”

Then McKay charged the students with looking up definitions of whatever words they chose. They excitedly called them out: Protest! Respectful! Queen! They raced to find the definitions and read them aloud.

As the students in Perna’s and Diana Ilisco’s classes settled down, McKay read a quote she had placed inside each students’ dictionary. “There’s a power in words,” it began. “There’s a power in being able to explain and describe and articulate what you know and feel and believe about the world and about yourself.”

McKay explained why the quote from singer Tracy Chapman was important to her. With new dictionaries, she told the students, they’d be able to better describe their thoughts and ideas. “It is important to use the right words to describe what you think,” she said. “No one can read minds.”

Photo via Communities in Schools