At eight years old, my best friend proudly served as an amphibian crusader in order to protect the toads of the Wissahickon from the many children who had little understanding of the impact human oils have upon toad skin. Young children are understandably still developing their sense of responsibility, yet still today mature and educated adults turn a blind eye to the creatures and habitats that suffer as a result of our human fingerprints.

My passionate primary and secondary teachers attempted to sow bits and pieces of knowledge which they hoped would flower into an environmental consciousness to reverse the havoc their generation had already wreaked. However, as I can unfortunately attest to from self-analysis and observation, my generation continues the trend of a collective consciousness that seems to have a convenient tendency to forget about our responsibility to our community and planet at times of self indulgence. Let me explain.

Our earthly water supply—the one planet and one supply we get (no back-ups)—is deteriorating fast. For years scientists have employed amphibians as indicators of water quality due to their absorbent skin (extremely susceptible to any toxins in their aquatic environment). Now, greater than 70 percent of all amphibian species are in decline. Amphibians are threatened by four main factors: disease, climate change, habitat loss and pollution, all of which are either created, transported, or inflicted directly by humans. This should be the time for humanity to own up to our flawed systems, and take responsibility for this man-made extinction. Instead, we promote adherence to the undesirable and outdated aspects of American culture that promote self-profit and appearance over ecological and community gain.

Not only do lawns cover more acreage than any one crop, they receive 20 to 300 percent more pesticide applications per acre than agriculture. Those of us who are passionate must convert this passion into time and commitment to maintaining a chemical-free lawn and life.

An American upbringing instills the need to display clearly-manicured, controlled, and efficient crops, a pleasing and well-manicured garden and, especially, an immaculate lawn in order to validate success. While most of my suburban neighbors have little understanding of food production, they are all incredibly proud to tend to their own street-facing strip of grass. And what is the cost of our American obsession, the swaths of suburbia in which each bright green lawn dims in repetition to become miles and miles of indeterminate plots of development?

As journalist Krystal D’Costa wrote in The Scientific American: “It’s the most grown crop in the United States—and it’s not one anyone can eat.” Not only do lawns cover more acreage than any one crop, they receive 20 to 300 percent more pesticide applications per acre than agriculture. Ninety million pounds of herbicides are applied on just lawns and gardens every year. What we still cannot manage to see is the trail of chemicals that runs right from our lawns into our Philadelphia waterways. These waterways are essential routes which pervade every aspect of our lives and communities, in addition to serving as essential, and very delicate, habitats for amphibians. Further, since Philadelphia water is entirely sourced from aboveground streams, the water we drink without a doubt originated from a creek bed which was purified and inhabited by our many amphibians.

![]()

Nevertheless, our soon to be state amphibian, the Hellbender Salamander, is close to reaching threatened status due to habitat fragmentation, and the deterioration of its aquatic habitat from eutrophication as well as the dissolution of chemicals from popular herbicides into its home. Even though Hellbenders (or Snot Otters and Mud Devils) don’t evoke the same human appreciation as a lawn does, their migration patterns and burrows benefit the entire stream ecosystem, something we desperately need. Pennsylvanians now have to consider what we want to display to the rest of the country: an oversaturated, yet green, lawn, or the slimy face of environmental balance.

While making this choice may seem simple, many are daunted by the process of shifting from a parasitic and highly-developed culture; however, Pennsylvanians across the state have the potential to create change by reducing pesticide runoff and pollution.

I support the creation of an outreach program that promotes alternate methods to pesticides and chemicals directly to the companies and farms which are already paid by suburbia to manage their earth.

In order to persuade those still haunted by the thought of spending extra time, I support the creation of an outreach program that promotes alternate methods to pesticides and chemicals directly to the companies and farms which are already paid by suburbia to manage their earth. These companies and organizations exist in the form of lawn management companies, farmers and farm corporations, and even the Neighborhood Gardens Trust, which manages 55 community gardens across the Philadelphia area. These groups would be presented with either educational speakers, workshops, or subsidies to encourage the use of Integrated Pest Management (IPM), the best alternate solution to chemical control.

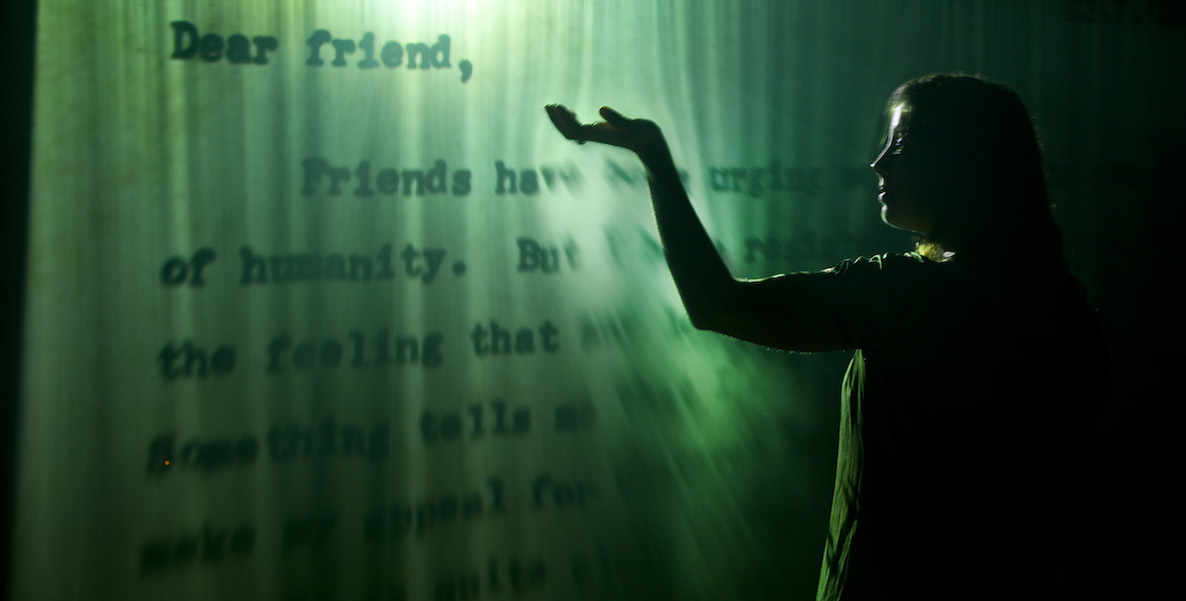

![]()

IPM, in fact, does not completely eliminate pesticides, which makes it less threatening to many lawn and farm managers. It does, however, entail pest and soil analysis to determine pest species and soil fertility. Further, no-till agriculture methods, or inter-cropping would be applied to increase fertility without added tilling and chemicals, and subsidies for these programs would go towards the purchase of organic manure and mulch that naturally eliminates weeds and fosters healthy crop growth, in addition to the input of biocontrol practices in which farmers introduce natural predators of targeted pests.

![]()

By participating in educational programs and clearly demonstrating a pesticide usage below a designated level, these companies would receive public certification for responsible pesticide use, which, similar to LEED certifications, would promote the company’s consumer reputation. Together, these Integrated Pest Management programs would significantly decrease the need for traditional pesticides, while maintaining company costs. Better yet, these methods can be applied from large lancaster farms to Roxborough suburb lawns and to underserved areas of downtown Philadelphia, creating a statewide restraint of toxic pesticide runoff, and a better educated population on healthy, functioning ecosystems.

Finally, for those conscious Philadelphia citizens who I hope have received this message, never fret: there is always a way for you to contribute. Those of us who are passionate must convert this passion into time and commitment to maintaining a chemical-free lawn and life. Whether that means hiring a reputable natural lawn service, or steaming weeds and applying vinegar instead of pesticides, I urge all of us to seek out ways to return our properties to the way they were created to function. By that I mean I am trying to make my green spaces truly green, and I hope you will too.

Hadley Ball is a senior at Penn Charter, hoping to work in the field of environmental conservation. She was one of 166 students to submit essays in the contest, in partnership with the Philadelphia Zoo, to answer a prompt about water, and its importance to people and wildlife—in particular amphibians. She won a $10,000 scholarship, $5,000 to implement her idea and an invitation to last week’s Zoo Gala.

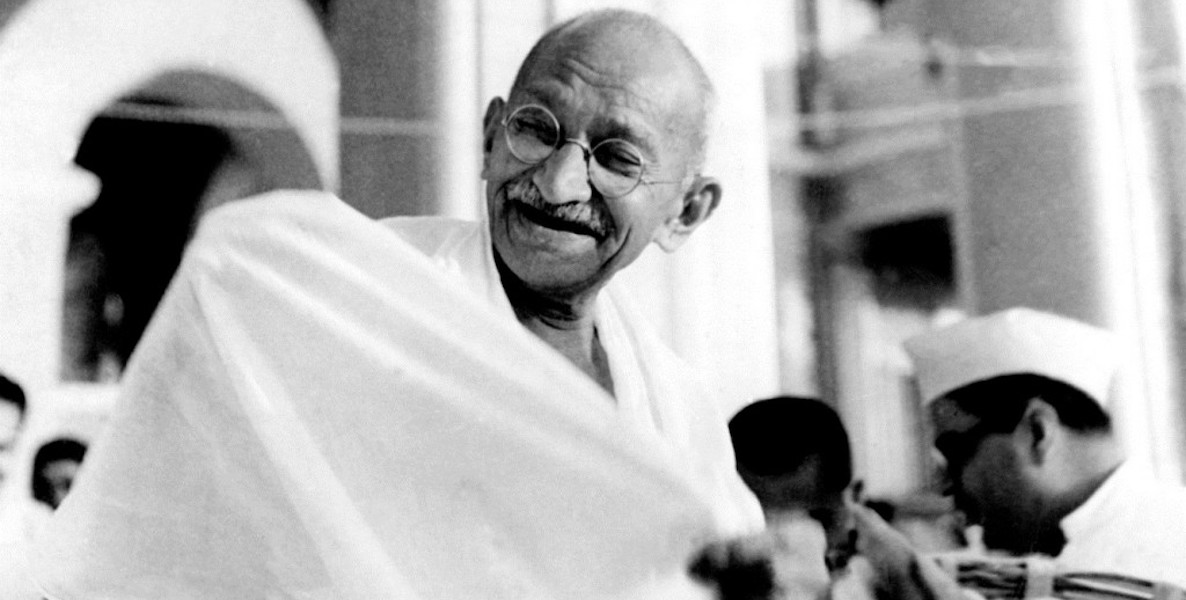

Photo by CDC/Dawn Arlotta via Public Health Image Library