To get our minds around the problem of mass incarceration, we often resort to numbers. About 2.3 million in prison nationwide. Seven million when we include the “correctional supervision” of probation and parole. That’s our city five times over, a population greater than most states, a number that not even the police regimes of China and Russia can touch.

For explanations, we look to history, Philadelphia history in fact. Here at Eastern State Penitentiary we made the bargain first in 1829: less torture with whips, more torture with time. We look at our history of racial oppression, its stark reflection in the color of the prison population. Also: the war on drugs, the collapse of the industrial base, and other decades-large shifts.

But in the math and macro-history, we lose people, individual lives. This is the problem in a nutshell.

But how do we re-humanize the system? One method is “participatory defense”, an approach used in jurisdictions from San Jose to Norristown, that invites the families and friends of those accused or convicted of criminal charges to help with their defense. This can include everything from finding witnesses, presenting evidence and corroborating alibis, to creating so-called “mitigation packets”—personal histories, character references, family pictures and home movies that present a fuller picture of a defendant. Participatory defense members also serve as each others’ support systems, sitting together in court, sharing knowledge and attending weekly workshops to focus their efforts.

This model of inviting the community into the defense team began 10 years ago in San Jose, California, through the worker advocacy organization Silicon Valley De-Bug. Led by Raj Jayadev, a young factory worker turned muckraking journalist, the method formalized under the Albert Cobarrubias Justice Project and has since spread to a dozen “Justice Hubs” across the country, including Philly suburbs Norristown and Pottstown. By comparing original sentences with those ultimately given, the Justice Project says that Participatory Defense has cut 3,350 years from offenders’ sentences.

That’s 33 centuries of “time saved.”

Participatory Defense addresses a crucial point often overlooked in our understanding of mass incarceration: the imbalance between prosecution and defense of indigent defendants.

The powers and resources of prosecutors dwarf that of publicly-funded defenders. While the Philadelphia Defenders Association has a larger budget—$45 million to the DA’s $38 million—prosecutors have a police force, investigators, forensic experts and medical examiners at their disposal, and they are led by one of the most powerful politicians in the city.

At the Defenders Association, the numbers are not conducive to good lawyering. Attorneys in the misdemeanor division take on about 700 clients per year, according to Philly’s chief Public Defender Kier Bradford Grey; felony defenders work 350 cases per year. That means public defenders with clients facing charges of rape, kidnapping, arson, or murder, have on average less than a day to devote to their defense.

According to Philly’s chief Public Defender Kier Bradford Grey, felony defenders work 350 cases per year. That means public defenders with clients facing charges of rape, kidnapping, arson, or murder, have on average less than a day to devote to their defense.

And many of the city’s poor defendants are not even able to be represented by the Defenders’ Association because of conflicts, as when more than one person is charged with the same crime. Instead, they are given court-appointed private attorneys, who make a flat fee of at most a few thousand dollars—with no additional money set aside for investigators, and often little time to search for witnesses or create mitigation packets. (A recent court ruling to raise the fees slightly has not yet taken effect.)

What these clients don’t get is what well-heeled defendants can afford: Private attorneys, who charge hundreds of dollars an hour, can hire investigators to track down witnesses, have specialists to create mitigation packets, and can pay for expert testimony. The two-tiered system means that poor defendants—even those who are innocent—are often poorly-represented, take more plea bargains, and wind up with longer sentences. It’s this inequity that Participatory Defense tackles.

“We don’t have the opportunity to understand who these people really are,” Grey says of the defender’s clients. “We need more help. We need more intel from the neighborhoods. We need them to tell the stories that only they can tell.”

Before Grey came to Philadelphia, she was the Chief Defender in Montgomery County, the first African American and the second woman in that office, where 30 defenders were staring down 15,000 cases. “We were dying for a way to articulate who our clients really were, their potential, their human capital,” Grey says.

In 2015, Grey watched Jayadev present his Participatory Defense model at a defenders conference in California. “My wheels started spinning,” she says. “I thought this is it, this is it.” She brought the model to Norristown shortly after.

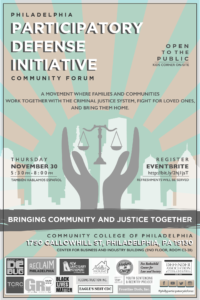

Now, she’s hoping to also bring it to Philadelphia. On Thursday, the Defenders Association is inviting the public to the Community College of Philadelphia for a conversation with Albert Cobarrubias Justice Project, pioneers of the program, and community organizations from across our city to discuss ways to make that happen.

In two years Participatory Defense Norristown has reduced the sentences of 90 people by 78 years—without advanced law degrees or great stores of money. That’s about 3.33 million tax dollars saved.

In Norristown, every Monday evening for the last two years, Participatory Defense Montgomery County has held a meeting just a block from the courthouse in the second floor conference room of CADCOM, the Community Action Development Commission of Montgomery County, a storefront nonprofit offering job training, parenting support and more.

I attended a meeting one recent Monday. Half a dozen people, family members of the accused and incarcerated, took seats around several tables pushed together. Heather Lewis, a CADCOM director, manned before a whiteboard. The whiteboard proved essential, as Lewis wrote the key steps in squeaky marker:

Name, Update, To do.

Under Name the group listed each person, either accused or convicted, whom the group will defend.

One-by-one, each name went through an Update, an outline of their case compiled by dockets sheets, newspaper articles, and personal knowledge. As their case took shape in whiteboard columns of names, dates, court motions and more, the group identified points of influence, places where they can apply pressure.

At To-do, the participants composed a plan that addressed those point of influence.

Three hours and eight names later, my mind was blown. Each Name and Update creates a logic puzzle with someone’s future at stake. Each To do is a succinct solution of motions. I have a side gig summing up case news for lawyers, but I drowned in the depth of legal knowledge in this conference room.

Here are just a few of the accomplishments laid out that evening, names withheld:

- A family man with drug-related priors who was facing decades in prison for a robbery to get his fix will instead serve three years, two of which will be in rehab.

- Another man who was just convicted for 2nd degree murder on a prosecution that had no ballistics, no DNA, and no eye witnesses, is headed into his appeal. His family and friends are mobilizing to create a mitigation packet and find a new lawyer that will, with their help, contest the weakness of the evidence.

- A woman whose son is serving life without parole for murder has found an unorthodox way to enter evidence previously suppressed—statements from witnesses near the scene of the crime, DNA issues, and more—into the record. Aided by the knowledge and support of Participatory Defense, she’s filing an amicus curiae brief, entering evidence as a “friend of the court.”

Whether each case rings with an optimistic note, or one of cautious reserve, the Justice Hub participants feel power. In two years they have reduced the sentences of 90 people by 78 years—without advanced law degrees or great stores of money. That’s about 3.33 million tax dollars saved on the back of $10,000 in grants, just enough to cover court transcripts and snacks.

But no one talks numbers here. For the participants, the results mean parents home with children, sons and daughters home with parents, families made whole.

![]()

RELATED

Header photo: Max Pixel