Last Friday night, local fashionistas, football aficionados and social justice warriors converged on the Center City restaurant Maison 208 for a party thrown by Jay Amin and Eagle All-Pro safety and activist Malcolm Jenkins, the co-owners of Washington Square’s Damari Savile, the bespoke men’s fashion store. Attendees were treated to heartfelt comments from Mayor Jim Kenney, Bearn Suntory craft cocktails, hors d’oeuvres courtesy of Chef Sylva Senat, and a fashion show to benefit Menzfit, the nonprofit that provides professional interview clothing, career development and financial literacy services to low-income men, including the formerly incarcerated.

Be Part of the Solution

Become a Citizen member.But a surprise also awaited the evening’s attendees, courtesy of Jenkins. You see, it wasn’t until after the fashion show that Jenkins revealed to the well-heeled crowd that those decked-out models they’d just oohed and ahhed over? They’re ex-offenders.

“A lot of us have an assumption about what it means to be an offender,” says Jenkins, who, when not picking off passes in the Eagles backfield, will be writing a column about criminal justice reform for The Citizen this season. “They’re violent, dangerous, uncontrollable. When we see that Scarlet Letter, we automatically judge them. We didn’t announce who they are until after the show because we want you to really stare in the mirror and think about what you think ex-felons look like.”

It’s fitting that the 29-year-old Jenkins is trying to get us to look in the mirror and question our preconceptions. Because, after the shooting deaths by police last summer of Philandro Castile in Minnesota and Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Jenkins looked at himself and decided he wasn’t doing enough. So he started studying issues of criminal justice reform. “I always had opinions,” Jenkins says. “I’d see things happening, but I’d be very reactionary about it. I’d see a video going viral and I’d post something about it. That was the extent of my role in social justice — I didn’t pay attention to the ways to change behaviors or find solutions. But then after Philandro and Alton Sterling, I realized we needed to stand together to figure out how to change results. I turned to the literature to figure out how to make the changes I wanted to see. And that meant starting this journey of learning how this criminal justice system actually works.”

![]() As he’ll chronicle this season at The Citizen, what followed were police ride-alongs, meetings with elected officials, campaigns to enact laws and reforms, and the marshaling together of fellow professional athletes to make their voices heard. “I’ve spent the last year hearing the opinions of those in law enforcement, the community, people behind bars, and exploring the political atmosphere when it comes to criminal justice reform,” Jenkins says. Each week during the Eagles season, he’ll give Citizen readers a 50-yard-line seat from which to view this improbable journey—along with a chart that compares the data of our criminal justice system with those of the cities his team plays each week.

As he’ll chronicle this season at The Citizen, what followed were police ride-alongs, meetings with elected officials, campaigns to enact laws and reforms, and the marshaling together of fellow professional athletes to make their voices heard. “I’ve spent the last year hearing the opinions of those in law enforcement, the community, people behind bars, and exploring the political atmosphere when it comes to criminal justice reform,” Jenkins says. Each week during the Eagles season, he’ll give Citizen readers a 50-yard-line seat from which to view this improbable journey—along with a chart that compares the data of our criminal justice system with those of the cities his team plays each week.

Athletes punch above their weight when it comes to influencing civic life; just imagine, after all, how world class Philadelphia would be if an army of Eagles fans took their cue from Jenkins and cared about their city as much as they care about the Birds on Sunday. Jenkins believes he has an obligation to make a difference beyond the gridiron.

In addition to agitating for criminal justice reform, the Malcolm Jenkins Foundation hosts Get Ready Fest, distributing 25 pounds of non-perishable food per family in underserved communities while offering medical screenings and providing job training, GED and veteran support services.

Then there’s the Summer STEAM program Jenkins and Drexel University offers students from West Philly’s Promise Zone, a free six-week camp curriculum that exposes students to a science, technology, engineering, arts and athletics, and mathematics curriculum. Jenkins even enlisted the Eagles strength and conditioning staff to teach students how technology impacts NFL players’ training.

Athletes punch above their weight when it comes to influencing civic life; just imagine, after all, how world class Philadelphia would be if an army of Eagles fans took their cue from Jenkins and cared about their city as much as they care about the Birds on Sunday. Jenkins believes he has an obligation to make a difference beyond the gridiron.

Jenkins’ good works don’t end there. There’s an annual holiday dinner for families in need, there’s a free football camp for kids, and there’s the coalition of more than 40 NFL players Jenkins and former NFL player Anquan Boldin—who attended last Friday night’s party—has put together to impact criminal justice reform.

And now comes Jenkins’ collaboration with MenzFit, a nonprofit whose mission is ensuring long–term gainful employment and financial fitness to low–income, primarily minority men with little formal education. MenzFit provides professional interview clothing, career development and financial literacy services, and Jenkins’ Damari Savile will hold a clothing drive throughout September and once a month thereafter for the public to donate gently used suits that can be passed on to MenzFit’s clients.

![]() Why the collaboration with MenzFit? Because, while on his criminal justice system listening tour, Jenkins found himself, accompanied by his teammate Steven Means, at Graterford prison in conversation with six inmates, four of whom are in their thirties and are juvenile lifers without parole; turns out, shamefully, that Pennsylvania leads the nation in juveniles sentenced to life without parole.

Why the collaboration with MenzFit? Because, while on his criminal justice system listening tour, Jenkins found himself, accompanied by his teammate Steven Means, at Graterford prison in conversation with six inmates, four of whom are in their thirties and are juvenile lifers without parole; turns out, shamefully, that Pennsylvania leads the nation in juveniles sentenced to life without parole.

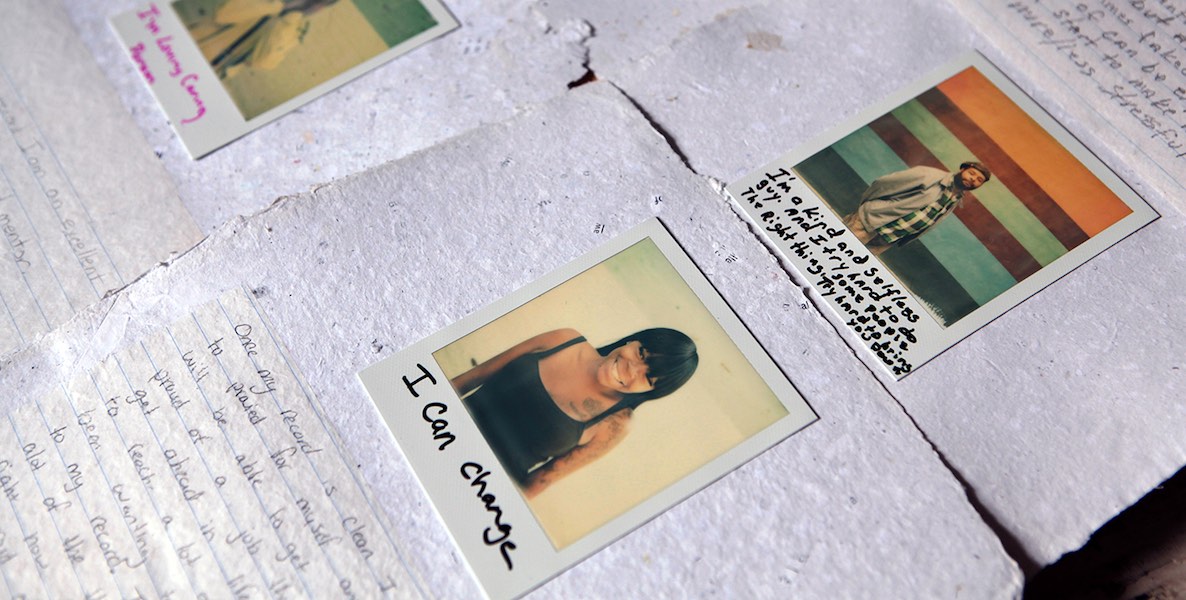

“We listened to their struggles, heard about the mistakes they’d made when they were young, and what their lives are like inside,” Jenkins says. “Some of these guys made bad mistakes when they were 14, but now they’re 35. I’m thinking, ‘I’m 29 — I’ve changed five times over since I was 14.’ I hope some of the guests at our fashion show said something like that to themselves when they met the models Friday night.”

Header photo: Malcolm Jenkins and Jay Amin. By Chris Ayala