In a 1993 speech to his city’s business community, former Boston Mayor Raymond Flynn laid bare an accepted truth in American politics: “Public education is an area that can swallow up the most promising career, and politicians are counseled at every step to ‘stay away from the schools.’”

Be Part of the Solution

Become a Citizen member.This was a year after Flynn, in his third term, became the first big city mayor in modern America to advocate for, and eventually get, the power to disband his city’s fractious, elected school board and appoint his own seven member schools committee in its place. While Flynn himself didn’t stick around long enough to reap praise or blame for the schools under his watch—he resigned in 1993 to become Pres. Clinton’s ambassador to the Vatican—many credit his move as being the first step in turning Boston’s schools into the best urban district in the country.

Prefer the audio version of this story? Listen to this article on CitizenCast:

Since then, several cities have followed suit—including Chicago in 1995, New York City under Mayor Bloomberg, Providence, and Washington, D.C. It has taken 25 years for Philadelphia to have a mayor politically brave enough (and a governor willing enough) to wrest back control of the school board, and put the success of schools at the top of his agenda.

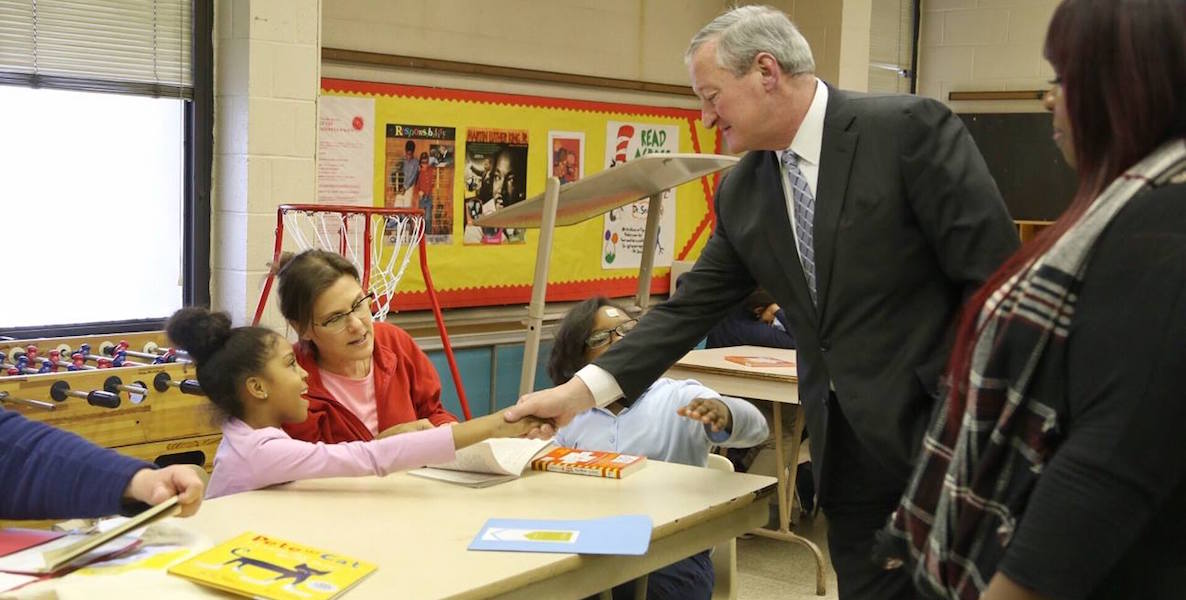

In his most recent address to the Chamber of Commerce in February, Mayor Jim Kenney made clear that he knows the political stakes. “Ultimately, I—and all future mayors—will be responsible to the people of Philadelphia when it comes to supporting our schools,” Kenney said. “As Mayor I am not only willing, but eager, to take on this responsibility because the success of our education system is critical to our city’s future.”

Could Kenney use his new mandate to form a sort of “childrens cabinet” that focuses city departments, social service agencies, businesses and the general public around the cause of raising healthy, educated children for the good of everyone? Does he have what it takes to articulate a shared vision that can lead to a public—shared—campaign, instead of one-off “do it for the kids” tax increases?

Those are bold words, that carry the weight of bold promises. But what, exactly, is Kenney promising? In his budget address to City Council, Kenney ran down a list of of areas in which we can expect to see “steady and incremental progress each year”—including expanding literacy coaches, capital improvements, increased 9th grade academies to prevent dropping out, more counselors and apprenticeship programs. That’s a vague metric by which to judge success. And two weeks into the new board’s first iteration, neither Kenney nor his education chief Otis Hackney have given much detail about what we should expect from them.

Instead, Hackney points to Superintendent Bill Hite’s Action Plan 3.0, a detailed outline for school improvement that Kenney has said he supports. And he calls for a bit of patience while the board organizes, meets with community members and starts to articulate its priorities: “People underestimate how hard it is to build up a board from scratch,” he notes.

Patience is reasonable—up to a point. It took four years in Boston before Flynn’s successor Thomas Menino devoted a now famous 1996 speech to that city’s Chamber to education, outlining a multi-year strategy called Focus on the Children with specific goals around instructional improvement, professional development, data and community involvement. “If I fail to bring about these specific reforms by the year 2001, then judge me harshly,” Menino implored Bostonians.

On the other hand, that was 22 years ago. We are way behind where we should be in educating our children.

As the board starts its hard work, there are some lessons to be learned from other cities with mayoral oversight of the school board—and some questions to consider here:

Consistency matters. In Boston, which has no mayoral term limits, Menino held the post for 20 years, enough time to form, articulate and see his vision through for the long haul. In that time, the city also had one superintendent, Thomas Payzant, who served for 11 years, almost unheard of in the annals of urban schools, where the average tenure is just over three years. (Another schools chief, Carol Johnson, lasted five years.) “One thing that bedevils school districts is churn,” says Paul Reville, former Massachusetts education secretary who is now a Harvard University education professor. “The most obvious symptom of coherency in Boston was having long term superintendents.”

In Philadelphia, Hite is already into his sixth year as superintendent, twice the average stay. His second five-year contract runs through 2022, and he has said he’s excited to work with the new group, which will oversee him and his budget. But will he remain in the post long enough to help shape and enact a plan from the new school board? Or will we be starting over, with a new superintendent, within a few years? That remains to be seen.

![]() Meanwhile, school board members have terms that run concurrent with the city’s mayor, which means—at the most—another six years, assuming Kenney is reelected. After that, a new mayor could bring a new set of principles to the schools. That doesn’t necessarily bode poorly. Kenneth Wong, a Brown University education professor and author of The Education Mayor, says that in cities across the country, the second or third mayors to oversee schools have taken up the mantle like their predecessors. “The idea of mayoral leadership, once started, passes from one generation to the other,” Wong says. “It becomes part of the job.”

Meanwhile, school board members have terms that run concurrent with the city’s mayor, which means—at the most—another six years, assuming Kenney is reelected. After that, a new mayor could bring a new set of principles to the schools. That doesn’t necessarily bode poorly. Kenneth Wong, a Brown University education professor and author of The Education Mayor, says that in cities across the country, the second or third mayors to oversee schools have taken up the mantle like their predecessors. “The idea of mayoral leadership, once started, passes from one generation to the other,” Wong says. “It becomes part of the job.”

Integration is key. Traditionally, school boards are laser-focused on their mandate: Overseeing K-12 schools. Mayors, though, have broader visions and a broader audience. “Mayors are responsible to the whole city,” Wong says. “They need to speak to the needs of all the residents, and the taxpayers, and they are aware of the dynamic that people can vote with their feet.” That responsibility also comes with leverage: Mayor Kenney’s new authority could allow him to bring businesses and universities and philanthropic organizations together for the cause of public education—a joining of forces not common to the way Philly usually operates.

In his February speech to the Chamber, Kenney characterized schools as the “most important long-term talent development pipeline, critical for business growth and attraction.” A few days later, he asked Council to pass an increased property tax, and to halt the reduction in wage taxes, in addition to last year’s soda tax—none of them strategies that particularly promote the sort of business-friendly environment we need to bring in more jobs.

Traditionally, school boards are laser-focused on their mandate: Overseeing K-12 schools. Mayors, though, have broader visions and a broader audience. “Mayors are responsible to the whole city,” Wong says. “They need to speak to the needs of all the residents, and the taxpayers, and they are aware of the dynamic that people can vote with their feet.”

Could Kenney instead use his new mandate to form a sort of “childrens cabinet”—like they have in Providence and elsewhere—that focuses city departments, social service agencies, businesses and the general public around the cause of raising healthy, educated children for the good of everyone? Does he have what it takes to articulate a shared vision that can lead to a public—shared—campaign, instead of one-off “do it for the kids” tax increases? Could he be the catalyst for bringing in new partners, to form creative solutions to funding and other problems?

![]() “With mayoral control of schools, everyone becomes more willing to invest because they see it as part of a continuum,” Wong says. “Cities can move resources around, and bring in others to help, because the Mayor is leading the conversation.”

“With mayoral control of schools, everyone becomes more willing to invest because they see it as part of a continuum,” Wong says. “Cities can move resources around, and bring in others to help, because the Mayor is leading the conversation.”

Hackney points to at least one area in which the Mayor’s larger agenda will influence his new school board: Workforce development. Outside of a few technical training programs, the School District has not robustly prepared students to take skilled jobs right out of high school—a path to making a living wage for those who are not going to attend college. Kenney’s new Office of Workforce Development, launched last month, is tasked with skills training and job placement. “With a local school board, they can raise questions to make sure the District is also working on that vision,” Hackney says. “That will become part of what they push Dr. Hite and the school district to do.”

Patience is reasonable—up to a point. On the other hand, we are way behind where we should be in educating our children.

Mayors are not educators; they set the stage for educators. Academic progress takes time. But Wong says districts that have successfully undergone a shift to mayoral-appointed boards have, within a few years, seen some measurable gains: Credit ratings sometimes go up because the mayor infuses additional credibility to the district’s management, allowing them to save money when they borrow for capital improvements. That can lead to better facilities, or upgraded technology—something tangible that residents can point to. Stronger oversight can also lead to more and better educators joining the district.

![]() And Mayors, as the top elected officials in a city, can serve as the buffers between the politics of education and the work of educators themselves. With schools as his responsibility, will Mayor Kenney, for example, be a better lobbyist for state funding? Now that his progressive supporters, and the teachers union, got the local control they sought, will they be more willing to compromise? Will the Mayor be able to steer us away from the rancor and bitterness that has characterized education politics in this city for so long? Will he—can he please?—find a way to stop the yelling and unproductive name-calling at board meetings?

And Mayors, as the top elected officials in a city, can serve as the buffers between the politics of education and the work of educators themselves. With schools as his responsibility, will Mayor Kenney, for example, be a better lobbyist for state funding? Now that his progressive supporters, and the teachers union, got the local control they sought, will they be more willing to compromise? Will the Mayor be able to steer us away from the rancor and bitterness that has characterized education politics in this city for so long? Will he—can he please?—find a way to stop the yelling and unproductive name-calling at board meetings?

If not, we can hold him responsible for the failings. That’s what has happened in Boston, Reville says, where decisions about the schools have come to reflect residents’ views of their mayor. Last year, for example, when the district flubbed the way it changed start and end times for schools, Mayor Marty Walsh was the one who took the blame, almost as if it was a decision that came straight from City Hall. (Though, of course, it did not.)

None of this is the magical stuff of book learning, but it is the important stuff of setting the stage for learning. “We want to hold the mayor accountable for enabling conditions to support the educators to do their jobs so schools are functioning well, kids can learn and teachers can teach,” Wong says. “Mayors are uniquely positioned to do that.”

Solving this is hard. Yes, Boston is consistently ranked at the top of large urban school districts, in a state considered to have the best public education in the country. But even its progress is limited: Reville notes that even 25 years after school reform efforts to improve schools, there are still deep and persistent achievement gaps between well-off and poorer—often African American—students. The task, for Mayor Kenney, will be figuring out a way to use his new power to lift all boats, something—to his credit—he has talked about since his campaign.

Hackney isn’t yet able to point to a detailed plan for what Kenney’s school board will do. Instead, he points to the Mayor’s larger vision—vague in places, but coming in to focus in others—that he says this new responsibility helps to push forward. That’s a contrast to what Hackney witnessed in the first year of Kenney’s administration, when the School Reform Commission was made up of members appointed by former Gov. Corbett and former Mayor Nutter. “Whose vision were they following then?” Hackney asks. “Mayor Kenney has talked about education, poverty and jobs all being interconnected issues. We don’t think of them as disparate elements, and the Mayor’s job is to pull them all together to fit into the broader picture.”

Photo: Mayor Kenney Facebook