Most of the contenders of the Franklin Prize Social Innovation Award at Pennovation Center last Friday look and sound like what you’d expect of a competition for Wharton post-grads vying for $5,000 to launch a nonprofit to make Philadelphia better: Under-30, men in their spiffy gingham shirts, women in their spiffy cardigans, nervous or polished, determined to be the ones with the next big social impact idea.

But there’s one contestant who stands out, and not just because he’s the only black guy in the mix, and 6’2”, and a little less prep-school than the others. There’s also the matter of his recent, half-decade-long incarceration. As a matter of fact, that’s why he’s here.

Ken Green was a drug dealer for most of his adult life. He’s not proud of it; it landed him twice in prison, and he’s currently operating out of a halfway house. He describes dealing drugs as an addiction; he craved the attention and friendship that it garnered him, the feeling of unfettered bigness. The weird part of it all, he says, is that he didn’t need to sell drugs. His mother is a successful restaurateur and his brother does more than well as a stakeholder in a cargoship.

All entrants in the Franklin Prize competition seek to tackle some of the most prevalent societal ills—from food deserts to mass incarceration to homelessness.

When he was dealing drugs, he would use kids as go-betweens or junior dealers. His method for bringing them on board, in spite of knowing they were getting into something dangerous? “Videogames,” he says, with shame in his voice. “You don’t have to pay a kid cash, they just want a game. Take them down to Gamestop and ask what they want.”

Upon his release—Green got out last year, and has been developing his idea for an educational program called R-K-A-D-E from his halfway house in south New Jersey—he realized that he had, in a sort of incredibly macabre way, developed an insight into the minds of kids. Videogames, he saw, were an uncanny motivator; the promise of the newest Call of Duty or Madden could get kids to do things they wouldn’t otherwise.

If a new game could get a kid to deal drugs, why the hell couldn’t it get a kid to do her or his homework? Green’s idea for R-K-A-D-E is for an after-school program that wraps videogames into the learning process both by providing them access to educational help and allowing them access to videogames in return for proof of academic achievement. Green’s presentation impresses, but he stumbles a bit when one of the judges, former Mayor Michael Nutter, asks him about mentorship. Still, he gets a loud round of applause from a largely student and alumni audience of dozens.

R-K-A-D-E is one of six teams making a presentation at the pitch-party, but it is the only one headed by a non-Penn grad; Green’s post-incarceration mentor was actually the one who said he should enroll in the competition, and the drafting of his presentation involved several Penn students. The judges include former Mayor Michael Nutter; Nadya Shmavonian, an education advocate and director of Penn’s Nonprofit Repositioning Fund; Danielle Wolfe, executive director of the M. Night Shyamalan Foundation; and Marc Singer, managing director of Osage University Partners, which helps colleges pursue venture capitalism portfolios.

This is the first year of the Franklin Innovation Prize, offered by the Penn School of Social Policy and Practice, an initiative to generate interest in developing creative solutions to social issues—kind of a microcosm of SP2’s whole purpose. It stems from the school’s recent Top 10 project, an initiative that seeks to alleviate some of the most prevalent societal ills, from food deserts to mass incarceration to homelessness. All entrants in the Franklin Prize competition seek to tackle one of those issues.

Besides Green, the teams include New Beginnings Community, which seeks to provide former prisoners with economic opportunities; From Prison to Professional, which provides former convicts with vocational training; Transforming Work, which seeks to help connect Philadelphia youth to long-term employment; and Fresh Box, which connect folks in food deserts to fresh food.

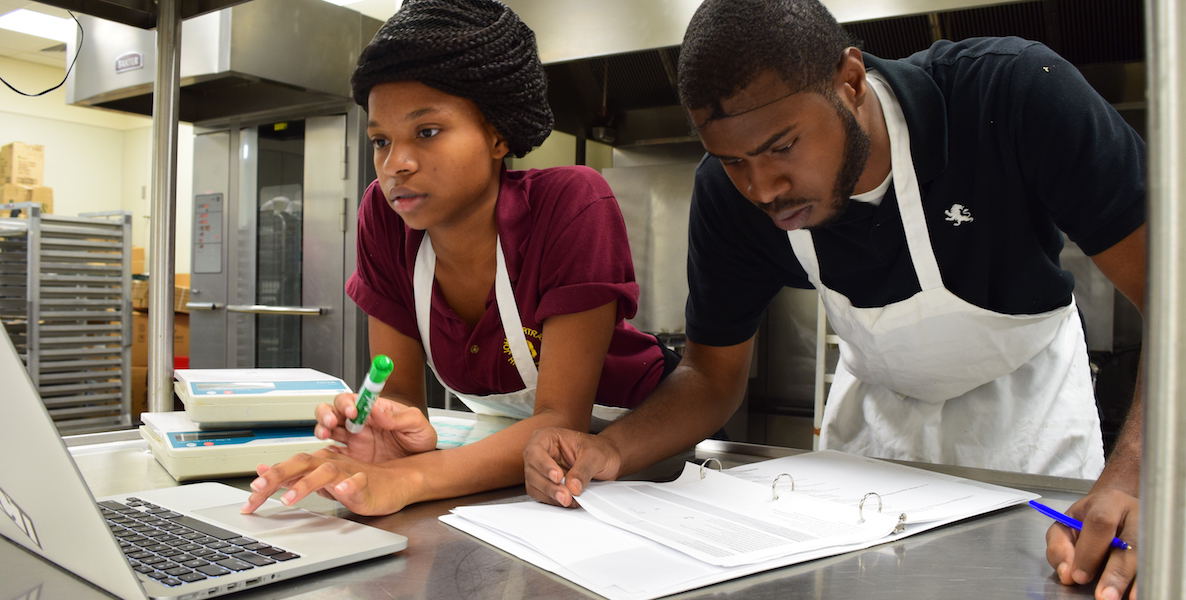

There’s also another education-related group, DreaMAPPers, a crew with an uncommonly un-snappy name, that is developing an app and concurrent face-to-face program that allows kids to set goals via phone or other electronic device and to have those goals overseen by educators who can confirm their achievement. They’ve worked with Strawberry Mansion High School, which has the lowest graduation rate of any Philadelphia high school at 38 percent.

After their presentation, they take a bit of a grilling during the Q&A portion with the judges. “How many people would be in charge of making sure the students met their goals?” asks Shmavonian. They stumble for an answer, but overall their showing is prim and the other contestants seem nervous.

It’s an interesting model that we’ve stumbled into, pitting one innovation against another in the hope that a panel of experts can divine the most profitable—or the most utilitarian. As a matter of fact, pitch wars have become a minor cultural obsession. Shark Tank is all about unrelated businesses squaring off for a pooled prize; TechCrunch’s Disruptor pitch series attracts thousands of applicants every year, looking for some of that sweet, sweet runway money. But the question is whether or not this kind of cutthroat, hyper-capitalist dog-and-pony aesthetic is conducive to the growth of non-profits and socially conscious startups, who aren’t seeking investors who want to profit, but are looking for partners who believe in them and want to support their vision?

The market evidence suggests that the process of unnatural selection is popular. Social Venture Partners, one of the nation’s foremost social impact and non-profit support organizations, holds annual nonprofit pitch competitions; regional non-profit pitch competitions occur across the country, from San Francisco to Boulder to Philadelphia.

The difference between for-profit and non-profit business pitch competitions, really, is in the prize money. For-profit competitions almost always have more in the pool. The winner of TechCrunch’s 2016 Disrupt pitch competition pulled in $50,000 and an unknown, undisclosed and presumably vast amount of concurrent investor money; Social Venture Partner’s Fast Pitch competition in Sacramento—their de facto California competition—has a total prize pool of $25,000 in 2017. Still, pitch competitions, as such, are good for business: They help fledgling nonprofits sharpen their pitches, teach them how to speak to potential supporters and, if they’re lucky, pull in a useful chunk of change to get things going.

In the end, it’s neither R-K-A-D-E nor DreaMMAPPers that wins the Franklin Prize of $5,000, but Fresh Box, which hopes to set up terminals from which people can order food to be delivered directly to their homes. Should they take off in Philly, they plan to expand to Camden, New York City and Detroit. Think of it as RedBox for healthy foods; it’s the kind of progressive, big-picture solution that the Franklin Prize judges are looking for. And, maybe, the sort of solution Philadelphia needs.

Header photo by Sheila Ballen for Franklin Prize