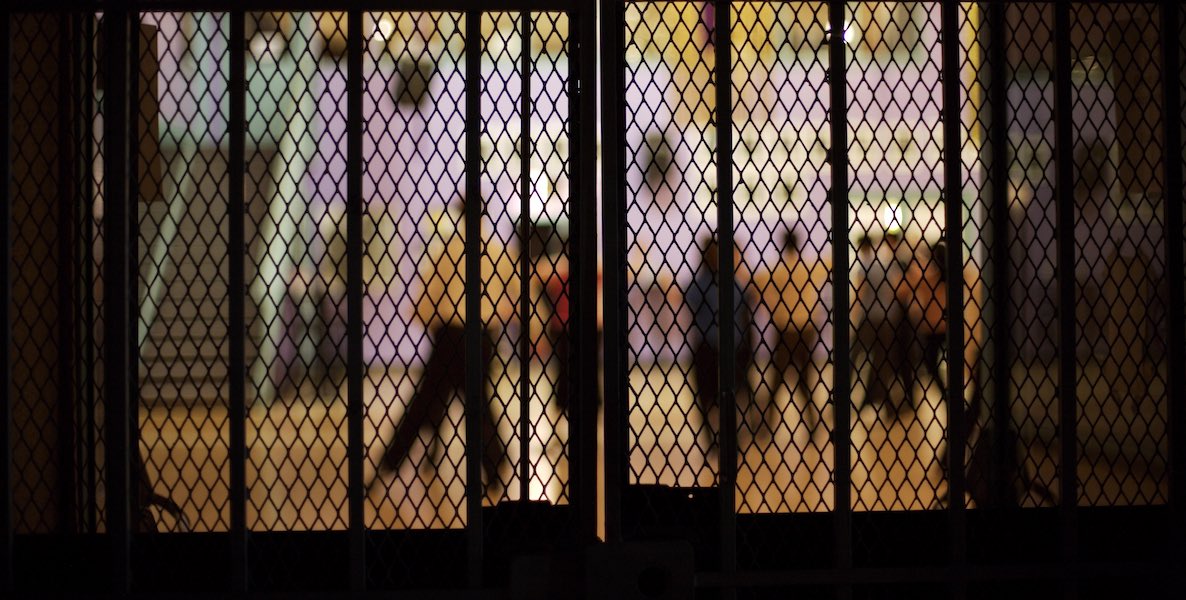

The true cost of failing to meet the needs of black male students hit me several years ago, when I was principal of a Philadelphia public school inside Curran Fromhold Correctional Facility.

One day, I met a former student from a public high school I had led several years earlier. I remembered that I had repeatedly suspended the young man from school for repeatedly cutting class. I felt it was the right thing to do at the time, for the sake of the school. But he was now an inmate, and still had not graduated from high school. I felt I had contributed to his circumstance.

And, in a way, I had. The rate of school suspensions has doubled in the last decade or so, most dramatically for students of color. In fact, the Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights says black students are three times more likely to be suspended or expelled—even as young as preschool. Meanwhile, a large-scale study out of Texas found that students who were suspended or expelled were three times more likely to encounter the juvenile justice system than those who stayed in school—a direct link in the schools-to-prison pipeline.

This contributes to the continuing disparity between white and black students. As a global report released in 2016 by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development noted, “The United States has made virtually no improvement in reaching its lowest performing students.”

Although the percentage of white students in the country has declined dramatically over the past 50 years, while the percentage of black students has changed very little, the achievement levels of black students compared to white students (and other racial/ethnic groups) has barely narrowed, according to a study by University of Illinois economist Steven Rivkin.

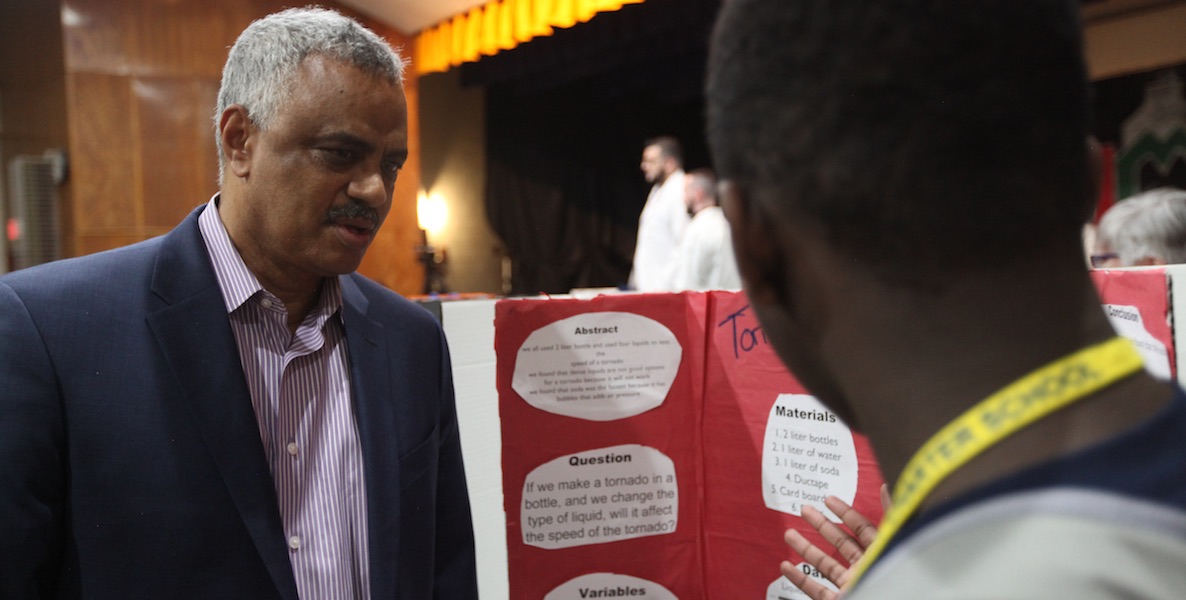

This is why school districts around the country have launched initiatives dedicated to lifting the prospects of black boys. In 2011, the Council of Great City Schools (an organization that represents 68 large urban school districts) administered a survey to collect information on what urban districts are doing to improve the success of black males in their schools. More than 20 school districts participated and offered solutions for black male achievement.

Voices from prominent urban educators suggest that black boys need to attend school regularly; they need a sense of belonging, intentional and purposeful instruction, and trusting relationships with their teachers. Simply put, they need teachers who sincerely care about them and want to see them grow socially, emotionally, and academically.

In Oakland, for example, the Unified School District launched the office of African American Male Achievement (AAMA) to fill the space left vacant by absent fathers or the lack of black male teachers. It offers a class with curriculum and resources to increase critical thinking skills and increase college readiness.

Until now, “the narrative of black boys in this city has always been around their deficits and what they are not doing,” says AAMA Executive Director Chris Chatman. That is now changing: Since its launch in 2010, the suspension rate for African American boys district-wide has dropped a third, and graduation rate has risen 10 percent.

In 2015, Washington, D.C., where only about a third of black male students are proficient in reading and math, invested $20 million in new support programs specifically for black and Latino male students in the district.

Here in Philadelphia, where a 2015 study showed that only 13 percent of African American males get a post-secondary degree of any kind, Boys’ Latin of Philadelphia Charter School in February launched #blackdegreesmatter to raise awareness of this issue and find ways to tackle it.

And Mastery Shoemaker principal Sharif El-Mekki (a Citizen contributor) is leading a national effort to encourage more black men to pursue careers in education as a way to support black boys in school.

According to El-Mekki’s group, The Fellowship: Black Male Educators for Social Justice, despite the District being 51 percent African-American, black male teachers lead only about 4.5 percent of Philadelphia’s classrooms.

A significant number of students go through school without ever experiencing a highly effective black male educator. (For the record, the number of black male teachers at my school is one. This lone black male teacher is an awesome classroom teacher. He is reaching and engaging all of his students, especially his black boys.)

Even former President Barack Obama got in on the work of saving black boys when he unveiled “My Brother’s Keeper,” a White House initiative to address challenges facing boys of color.

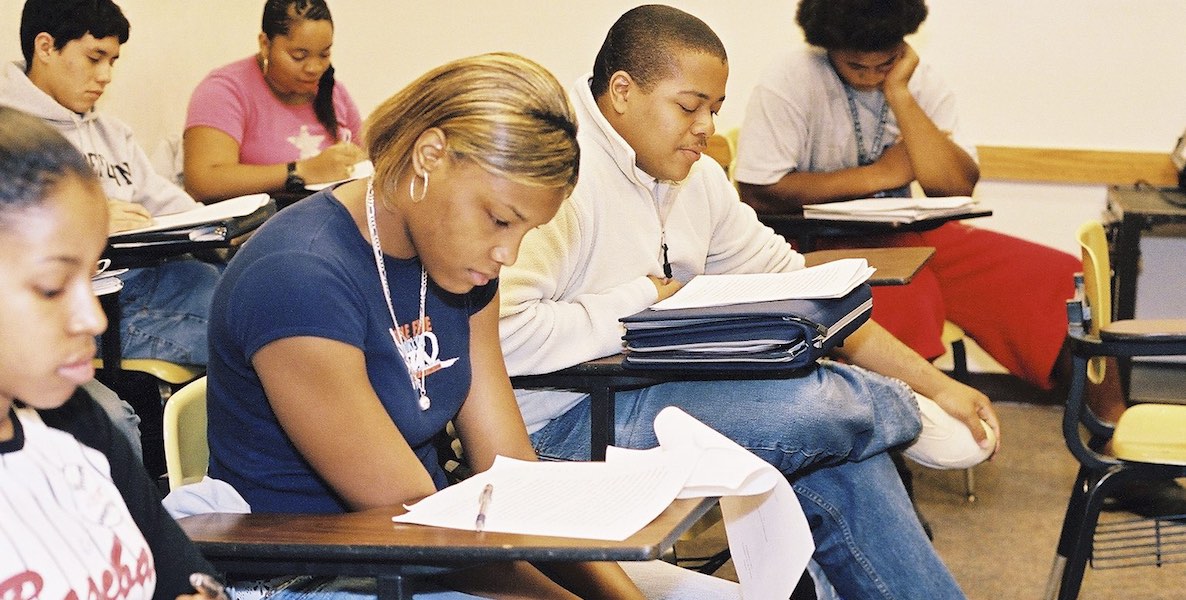

While these initiatives step up to address critical educational issues that affect black boys’ learning, I believe the reason for the problem with black male achievement is very simple: Black boys are the victims of low expectations from school teachers and leaders who are afraid of their behavior, of daring them to teach them.

In his book, Young, Black, and Male in America: An Endangered Species, J.T. Gibbs writes, “the majority of African American males, particularly those in urban centers, are categorized and stereotyped by the five Ds: dumb, deprived, dangerous, deviant, and disturbed.”

These stereotypes contribute to the fear among some educators concerning black boys, which dumbs down the instructional rigor that these students need to achieve a high-quality education.

Thus, black boys are more frequently identified for special education. They are referred for behavioral health services. Their school behaviors are criminalized, and teachers dole out poor grades as a method of discipline.

I have had teachers who have yelled at black boys because they stood up at their desk while doing their classwork. I have had teachers who have asked me, even before the lesson began, to remove “the rough boys” from their classrooms because they might be a problem. I have had teachers consult me about bringing criminal charges against black boys because of incidents that were very damaging, but could have been resolved by asking me to model the appropriate adult behavior to mend the student-teacher relationship. I have even had parents demand that I expel black boys, some coming to the school with police officers to have six-, seven-, and eight- year-old black boys arrested.

These factors only widen the distrust between black boys and their schools.

Voices from prominent urban educators suggest that black boys need to attend school regularly; they need a sense of belonging, intentional and purposeful instruction, and trusting relationships with their teachers. Simply put, they need teachers who sincerely care about them and want to see them grow socially, emotionally, and academically.

This has helped shape two of my key approaches to school leadership and working with black boys: Keep academics first (no matter what) and build trusting, authentic, educational relationships with all students.

This takes a deliberate approach. At Carnell, we work hard to keep academics first and cultivate a school culture that embraces all children. As I have said before, we have made changes to our instruction that have resulted in positive student growth every marking period. But far too many students still are not benefiting from the progress we are making.

As a global report released in 2016 by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development noted, “The United States has made virtually no improvement in reaching its lowest performing students.”

Many of those students are black boys. Black children make up 60 percent of our school’s population (and black boys account for nearly half that number). Despite our best efforts, there are black boys who are not reading on-target and struggle in classrooms.

This year, we implemented a four-tier parent-teacher-student intervention system to influence academic performance and help teachers, students, and parents engage, understand each other, and work together to expect more from these children, particularly black boys.

We are focusing on the development of teachers’ knowledge about black boys’ behaviors, using trauma-informed principles, that will improve the teacher-to-black male student relationship, help in learning to cope with the demands that black boys present, and sharpen instructional strategies that are meant to engage and respond to black boys. We are basing our instruction and supports on research and best practices—and we are seeing progress.

That progress requires constant attention throughout every aspect of the teaching day, and beyond. There is no other way. In the United States, we are failing black boys—both in school and in the larger society—and we must work to address their overall educational performance. Otherwise, we all fail.

Hilderbrand Pelzer III is the principal of Laura H. Carnell School in Oxford Circle. He won the 2014 Lindback Award for Distinguished Principal Leadership, and is the author of Unlocking Potential: Organizing a School Inside a Prison. Pelzer is contributing regular columns from the school front lines this year.