Most days, around 5 or 6 p.m., Candace Stanton, 36, maneuvers a black minivan into a parking spot across from the Dunkin’ Donuts on John F. Kennedy Boulevard, grabbing a snack from her bag as she waits to drive her crew to work.

The job?

Working past midnight, she and the others count lace undies at Victoria’s Secret, or men’s ties at Target, or cute little doggie hats at a Petco. “And they’re expensive,” marvels Celice Pearsall, 31, of South Philadelphia, who rides along in the van with her co-worker, David Mullen, who turns 53 next week.

Prefer the audio version of this story? Listen to this article on CitizenCast:

Mullen has been around long enough to know a simple fact of life in Philadelphia: The better jobs that pay more are in the suburbs.

And that, for the most part, makes them out of reach for someone like Mullen, who lives in Philadelphia, and doesn’t own a car. Only one in three Philadelphians do. In Nicetown, where Mullen lives, that drops 50 percent.

“Suburban Philadelphia has always been a source of better opportunity and with opportunity comes mobility, upward mobility, to move to a better job,” he says.

“Suburban Philadelphia has always been a source of better opportunity and with opportunity comes mobility, upward mobility, to move to a better job,” he says.

Mullen, however, has the counting job in the suburbs—steady, although not particularly lucrative —and he has it because he participates in the Philadelphia Unemployment Project’s Commuter Options program.

It’s a van pool program with workers driving themselves and fellow employees to jobs in the counties, where the unemployment rate is lower and employers need help. The riders pay $6 a day for a round trip, which helps offset the expenses for leasing the van, gas and maintenance covered by the program.

“It’s an ugly way to put it,” Mullen says, “but you have to swing from vine to vine looking for the best fruit. It’s about means and opportunities. When you have the means, you get the opportunities.”

![]() Everyone would like to see more jobs return to the city, says John Dodds, executive director of the Philadelphia Unemployment Project (PUP), an advocacy group for the unemployed and underemployed that has been pushing issues like increasing the minimum wage, foreclosure protection and transportation since 1975.

Everyone would like to see more jobs return to the city, says John Dodds, executive director of the Philadelphia Unemployment Project (PUP), an advocacy group for the unemployed and underemployed that has been pushing issues like increasing the minimum wage, foreclosure protection and transportation since 1975.

But, in the meantime, he says, it makes sense to get Philadelphians to where the jobs are. “We have a 1970 transportation system with a 2018 economy,” he says. “It leaves people isolated, without an opportunity to get ahead.”

Rolf Pendall, an analyst, researcher and urban planner who has been studying the interplay of transportation, housing, employment and poverty for years at the Urban Institute in Washington says that “access to unreliable transportation happens to the poor and it’s also something that makes people already on the margin become poor.”

A $367,000 grant from Pennsylvania Department of Transportation funds the program, which serves about 65 Philadelphians in 14 car or van pools. Dodd says $250,000 more from the city would boost the number of people served to 300 in 60 car pools.

People who don’t have a reliable transportation find it hard to get a job, and it limits the places they can look for work, he says. People who work split shifts, rotating shifts or at night have even greater difficulty using public transportation if it even exists. It’s particularly hard on single mothers with young children who juggle the demands of getting to work with demands of finding child care.

Most public transit systems, Pendall says, “aren’t able to allow low income people to juggle the many demands on their time.” More private car options are necessary.

Desperate to go to work, employees may save enough money to buy an unreliable car. When the car breaks down, he said, they may be in an even worse position, losing their workplace reputation for reliability, their jobs, or even their lives, if the breakdown happens in a dangerous place.

![]() Van pools can be part of the solution—but they rely on finding a group of people working at the same place and at the same time. “I don’t want to be pessimistic about van pools,” Pendall says. “They are a slice of what we need, but we need to think about more slices.”

Van pools can be part of the solution—but they rely on finding a group of people working at the same place and at the same time. “I don’t want to be pessimistic about van pools,” Pendall says. “They are a slice of what we need, but we need to think about more slices.”

In Philadelphia, PUP’s Commuter Options program began in March 2006 with one minivan. Now a $367,000 grant from Pennsylvania Department of Transportation funds the program, which serves about 65 Philadelphians in 14 car or van pools heading to jobs outside the city. That grant is now up for renewal.

Dodds says that the PennDOT grant plus $250,000 more from the city would boost the number of people served to 300 in 60 car pools, based on a volume leasing discount.

To make the case to the Mayor and City Council, Dodds’ staff drafted a report pulling together area unemployment rates, commuting patterns, car ownership statistics and a survey on employment barriers:

- Asked about barriers to employment, 39 percent of people living below poverty levels said access to transportation was the biggest barrier to finding or keeping a job, ahead of childcare challenges or criminal history, according to a 2016 Community Needs Assessment produced by the Mayor’s Office of Community Empowerment and Opportunity.

- In December, Philadelphia’s unemployment rate was 6.4 percent, in contrast to 3.7 percent in Chester County, 4.0 percent in Montgomery, 4.4 percent in Bucks and 4.6 percent in Delaware counties.

- In Philadelphia, all jobs are accessible by public transit, but in Bucks County 42 percent of all jobs cannot be reached by public bus or train, according to the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission.

- In 1970, 50 percent of the region’s jobs were located in the city, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported. By 2013, only one in four of the region’s jobs were in Philadelphia.

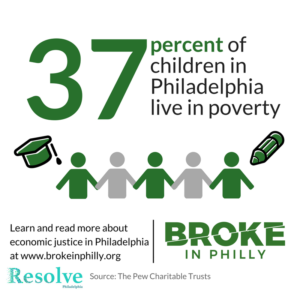

- From 1970 to 2015, poverty rates rose in every section of the city. In one section of North Philadelphia, the poverty rate nearly tripled, from 16.6 percent in 1970 to 45.4 percent in 2015, based on statistics from the U.S. Census bureau.

“There are many reasons for poverty, but one that we too often ignore is transportation,” Dodds wrote in his report.

He sees it as a form of institutional racism: “Not that some one individual is actively pursuing a racist outcome, but that that is the result of our current mass transit system that does not take into account the realities facing low income Black and Brown people in designing our public transit system.”

“It’s an ugly way to put it,” Mullen says, “but you have to swing from vine to vine looking for the best fruit. It’s about means and opportunities. When you have the means, you get the opportunities.”

That’s the overarching policy perspective.

For Celice Pearsall, 31, of South Philadelphia, it’s all about getting to work, even for a job that pays just $10 an hour.

Three years ago, Pearsall was earning $22 an hour working for the American Red Cross in data entry, a job she held for nine years, advancing through the ranks. “I was young, I had no kids. I went on vacation a lot and I had my own place,” she says.

But then, there were massive layoffs. Soon after that, she got pregnant. Her son is now two years old. She moved back in with her mother, and the car she owned was totaled in an accident. “Now I live check to check.”

![]() Pearsall, Mullen, and Stanton, who drives the van, all work for Rgis LLC, a national company with a local office in Holmes, Delaware County. Retailers hire Rgis to conduct audits and handle inventory. Sometime assignments take Stanton’s van pool to stores in Allentown, or Boyertown in Berks County.

Pearsall, Mullen, and Stanton, who drives the van, all work for Rgis LLC, a national company with a local office in Holmes, Delaware County. Retailers hire Rgis to conduct audits and handle inventory. Sometime assignments take Stanton’s van pool to stores in Allentown, or Boyertown in Berks County.

“I just put it in the GPS and drive,” Stanton says.

For Rgis hiring and training manager Desiree Graves, the Commuter Options program is a “helping hand,” She calls her contact at JEVS, which operates a job search program, and works with a representative at PUP. Soon, she says, she has a crew of people with transportation ready to work. This week, she’s about to build another crew.

“I’m looking to hire people if they can get back and forth to work on time,” she said. “I love this service, I really do.”

That squares with what JEVS job developer Everette Callaway says he hears from other employers about the program. “They are thankful that this van pool can help them meet their needs,” he says. “They think it’s the best thing since cornbread and iced tea.”

Celine Pearsall, left, rides a van to her job taking inventory at stores in the suburbs. At the wheel is Candace Stanton, who, in return for being responsible for the van, can use it for some short personal trips. They meet in Center City. Photo by Jane M. Von Bergen