There is an elephant in the room, standing in the way of effective teaching and student learning. Its enormous size is blocking an obvious truth that is going unaddressed: Poor teaching is hurting our children.

With the proliferation of school closings, school district takeovers, and the strong national support for school choice, charter schools, and privatization, one would think this issue would have been addressed by now. But it has not. It stands in the way of progress, while fast-moving educational changes happen around it.

I was inspired to become a principal over 25 years ago because I saw incarcerated students firsthand who had rejected education as if it were a deadly disease. Mostly black males, these students were unable to read or write their own names. Today, there are still children who cannot read or write their own names. They perform below basic levels in reading, writing, and math. These are subjects that represent the core of education. According to the global report “Low Performing Students: Why They Fall Behind and How to Help Them Succeed,” released in 2016 by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, “The United States has made virtually no improvement in reaching its lowest performing students.”

Good teaching is a combination of strategies such as planning, interpreting performance data, monitoring progress, and the will to educate all children, regardless of ethnicity, parental support or poverty. It requires the desire to deliver instruction to other people’s children with the same desire for success that one would offer one’s own children.

One major reason for low student performance is ineffective teaching in classrooms, which starts with ineffective teaching of would-be teachers. Former U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan brought this to light last year in an open letter to America’s college presidents when he wrote, “The system we have for training teachers lacks rigor and is out of step with the times.”

Good teaching—what we principals refer to as “instructional delivery”— is a combination of strategies such as planning, interpreting performance data, monitoring progress, and the will to educate all children, regardless of ethnicity, parental support or poverty. It requires the desire to deliver instruction to other people’s children with the same desire for success that one would offer one’s own children.

As I’ve mentioned here before, Laura H. Carnell school was one of the lowest-performing schools in the District when I became principal in 2012. I quickly realized one of the reasons for its poor performance was, frankly, poor instruction. The school struggled with and resisted collaboration, professional development, curriculum planning, and data-driven decisions. We had a high teacher absenteeism rate. Our teachers and staff often pushed responsibility for students’ low performance on external factors, rather than the way they were delivering instruction. Poverty was blamed. Parents were blamed. Students’ home lives were blamed. The child’s behavior was blamed. After becoming accustomed to low expectations for students’ abilities to perform at high levels, most teachers and staff found it comfortable.

That’s one of the main reasons I decided to become a District redesign school last year, with the primary goal of eliminating poor teaching practices that were holding our students back, rather than just improving our performance metrics and ranking among city schools.

Our most notable step has been paying attention to what our data was telling us about instructional delivery in our classrooms. It said that we were not teaching students how to become motivated learners and self-directed critical thinkers. And it said that ineffective teaching and student learning are driven by what teachers and students are not doing in classrooms, like creating measurable learning targets; allowing students to assess what they do, say, and produce against exemplars; designing intentional learning centers aligned to academic standards; inviting students to develop questions, write, and explain their work; and posting data walls that compel students to understand goals for their learning and growth, and track their progress toward those goals.

As a result, we made two major decisions. First, we asked existing teachers to reapply for their positions. In this case, we were looking for teachers who were willing and able to invest in new instructional strategies. The redesign initiative application process gave us the opportunity to select new teachers who embraced the school’s vision of becoming project-based learning school of choice for Philadelphia students. This led to the turnover of more than half of the teaching staff. Teachers whose values, priorities or skillsets did not align with the new direction of the school were either not invited back or chose not to reapply.

We were fortunate: The redesign process guaranteed investment in the new instructional approach. Schools should have staffing flexibility, such as promoting their unique models to prospective teachers to ensure that all teachers are opting into the model with a firm commitment to the school’s explicit instructional strategies and practices. According to a teacher who stayed, “We weren’t meeting our targets. We knew we had to do something if we wanted to avoid being closed or turned around. The people that stayed are the ones who were adaptable, but change is hard and not for everyone.”

Principals should not be let off the hook either. Their instructional vision should impart a strong focus on giving their teachers the tools to succeed and enabling them to take advantage of their students’ energy and interests.

The other major decision we made was to partner with EL Education, a nationally recognized organization that pushes schools to increase student engagement and raise student achievement. The group’s presence at our school is like having our own academic office, helping us make learning come alive for our students.

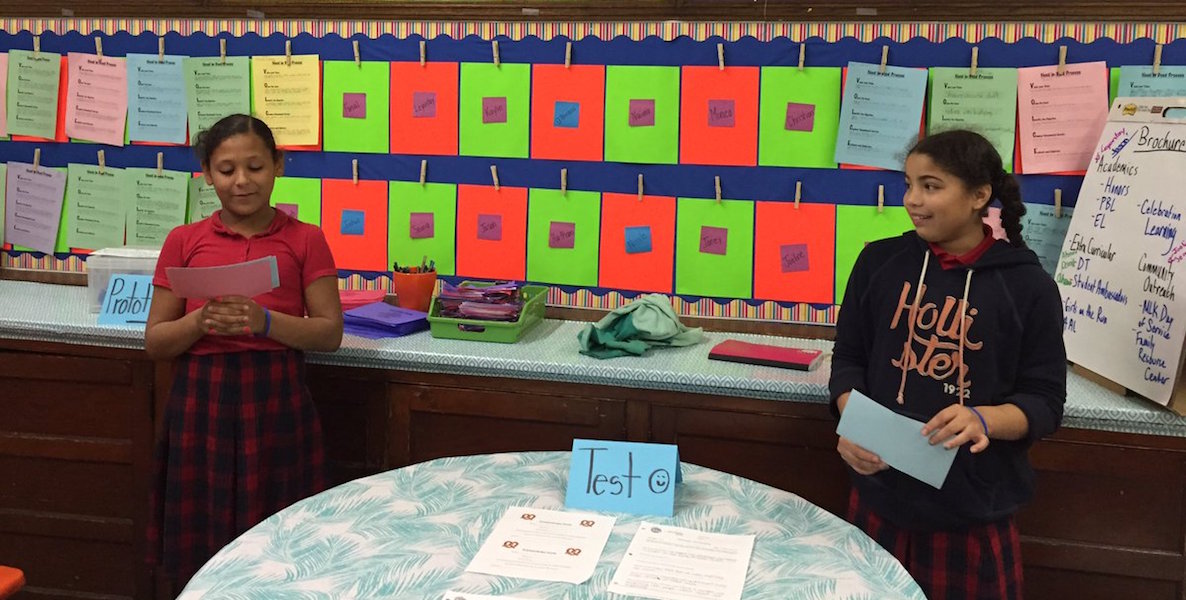

Today, all of Carnell’s classrooms follow some core practices, including: An urgency for improvement for all students, especially those in difficult situations and who start Carnell already trailing behind academically; lessons guided by learning targets; ongoing data analysis; on-site professional development; project-based learning. As a result, our students are improving. They are becoming leaders of their own learning. Our teachers are developing reliable teaching practices.

We still have work to do—as I’ve said before, we are making progress, but are not yet as successful as we need to be. Still, according to the 2015-2016 district-wide survey feedback, 65 percent of our students said, “I love schoolwork.” This is a powerful performance measure demonstrating that effective teaching and student learning is happening at Carnell.

Eliminating ineffective teaching is the right thing to do at any school. Seeing children struggle in classrooms, day in and day out, is incomprehensible. While it is tolerable to help teachers who strive to be excellent and effective teachers, it is flat out excruciating to accept keeping ineffective teachers who do not strive to improve their instructional delivery or the outcomes of their students.

Principals should not be let off the hook either. Their instructional vision should impart a strong focus on giving their teachers the tools to succeed and enabling them to take advantage of their students’ energy and interests. Principals and teachers must become knowledgeable about new instructional strategies and remain aware of developing research in public education, educational changes, and new innovative instructional strategies that are reaching children and meeting the academic needs of all students.

Carnell is taking advantage of being a redesign school. But good teaching doesn’t require that— or shouldn’t, anyway.

Hilderbrand Pelzer III is the principal of Laura H. Carnell School in Oxford Circle. He won the 2014 Lindback Award for Distinguished Principal Leadership, and is the author of Unlocking Potential: Organizing a School Inside a Prison. Pelzer will be contributing regular columns from the school front lines this year.

Header photo from Carnell Elementary on Twitter