If you live in a city, you have likely developed a certain skill. At least, you have attempted to. That is the skill to ignore the billboards, flyers and other visual noise designed to grab your attention. The truth is more complicated. We all know which jeweler Philadelphians are supposed to “hate,” even if we like to pretend otherwise. Galen Gibson-Cornell goes in another direction.

Trained as a printmaker, he appreciates that posters are thoughtfully designed to be charged objects. Instead of ignoring them, Gibson-Cornell asks, What can be done with that? Since that question first occurred to him almost a decade ago, he’s made wheatpaste advertisements that litter walls and construction sites the backbone of his work.

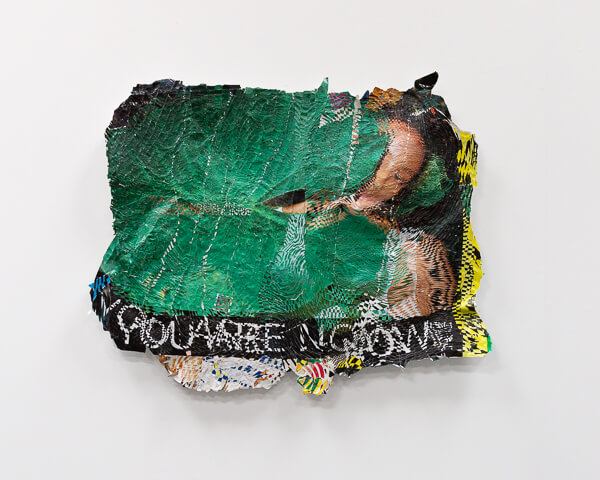

Gibson-Cornell is a wanderer who explores cities in an effort to recover its “urban skin.” When an image catches his eye, he rips it off the wall and takes it home. Back at his studio at Globe Dye Works in Frankford, he arduously turns that would-be trash into stunning artwork. Gibson-Cornell slices the salvaged posters into strips and weaves them together into vibrant collages that can reach ten feet across. With some pieces, a central image like a face or a hand is still decipherable, but it’s been distorted as though through a kaleidoscopic filter. Others are so abstract, with various different posters so obscured or mixed together, that they bring to mind an unfamiliar topographic map. Using recycled found posters as his core material, this printmaker-turned-weaver builds colorful scenes that reference his travels, the imperfections of memory and the language of street-level visual culture.

Gibson-Cornell has exhibited locally at the Philadelphia Museum of Art Craft Show and Bertrand Productions, as well as nationally at Poster House, Art on Paper and SCOPE.

As part of a partnership with Forman Arts Initiative, the Citizen caught up with Gibson-Cornell. The interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

RJ: When did you start paying attention to street posters?

Galen: I was living in Angers, France, where I came across a World War II-era photograph of the day that city was liberated. It showed a wall that had been covered in German political posters, and the newly-liberated residents of Angers were ripping those down. That wall is still around today, and there are still posters on it, these days for Radiohead concerts and whatever else. That continuation of history made me really interested in posters as archeological objects.

The process of posters coming up and going down made me think about an organism shedding its skin. And that action of the ripping is so symbolic. The German posters had symbolic energy, but so did reacting against them. I started to think, “Wow, there’s power in this.” That power, coupled with the fact that the paper is so fragile, is an interesting pairing.

And now you’re the one ripping these posters down, though not generally out of hatred. What is it like to wander through unfamiliar cities gathering this material?

I am driven by curiosity. I go to places because I want to experience what their streets look and feel like, and then I end up taking posters because I’m attracted to them, or I’m excited to see what I can make of them. It’s like having a sweet tooth and discovering a new pastry.

Do the posters vary from city to city?

Absolutely. I just came back from Berlin, and I have 100 pounds of posters strewn across my floor. The colors and text and everything in those posters are totally different than what I’ve been finding in New York. What I make is different based on where the source material comes from.

How did you come up with your process?

The weaving came from austerity. Working with posters takes so much space, and there were so many early fruitful seeds of what to do with them, but the artworks became huge. Imagine 50 copies of the same poster laid out in a grid. Interesting, but impractical. I had to come up with a way to condense. That’s where the weaving came in.

Did you grow up weaving or doing other crafts?

I didn’t have any background in weaving before this work. I arrived at it just because I like X-Acto knives and I’m comfortable working with paper. It made sense to me to cut the posters, and then it made sense for me to weave them. I love when people say, “Oh, I’m a weaver and I like your work because of this.” I like being able to butt up against other people’s disciplines and say hello.

How much of a piece do you plan out ahead of time? Where do you start?

People will notice some of the more chaotic elements, or come across interesting patterns in the abstract sections, and ask me if that’s something I planned on. It never is. The weaving is a task that sounds robotic, but it’s done by a human and the best parts are the little faults. Those aggregate into a ripple or a topography. That’s where the interesting visual moments develop.

The starting point comes from what I have on hand. If you ask me what my next piece is going to be, it might come down to whether I have multiple copies of an image that I want to work with. When I have duplicates, I can generally find a way to make a work using only that material. I like that restriction, and I think those pieces tend to resonate well. When I don’t have multiples of the same image, I get to work in a different way with color and texture, making things that are more abstract. That scratches an itch too, seeing what happens when I put a weird turquoise next to a red.

I operate in a mess, and that’s one way to get those colors next to each other. It leads to moments of inspiration. A lot of what I do, letting the posters or my mess guide the process, is un-tensing the muscles that are developed in graduate school. Deskilling the whole endeavor and finding unexpected moments in randomness.

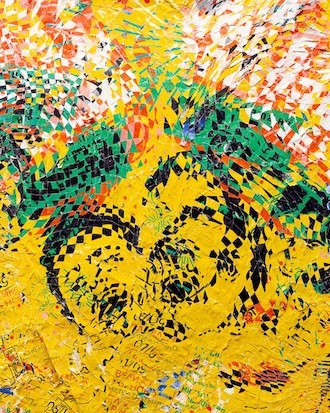

I love your piece Queen, which is a great example of what you do with duplicates of the same poster. How did that piece come together?

That weaving stems from my recent trip to Bulgaria. I was initially interested in working with some posters where the text was in a different alphabet. In this case, the text is Cyrillic. Bulgaria has a beautiful tradition of weaving and crafts, so I felt inspired already. I found many interesting posters in Sofia [the capital], including a group of mostly yellow ones, with lime-drawn figures and text.

I knew right away that I needed to combine these posters to make sort of a “unified” work. I like the repetitive “stuttering” that an image makes when I weave multiple copies of it together: It reminds me of digital glitching, which is fascinating to me because of how handmade everything I’m doing is. So this piece to me represents the complexity of multiple copies of a single image being presented in the same space, as well as an entirely analog artwork sidling up alongside some digital concerns.

When you’re working primarily with found materials people must ask: What are you, as the artist, contributing to the work? Why shouldn’t I be giving the credit to people who design these ad campaigns?

I started weaving posters because the lack of virtuosity is an interesting challenge. When I first started to make art, the thought was, I need to draw really realistically. I got bored with that, and the next question was, Can I do something that’s not so obviously talent based, but can I do it in such a way that it still has a wow factor?

The goal I’ve been chasing is to see if I can do something dumb and meaningless on a small scale in such a large, interesting or exact way that it becomes meaningful. It’s dedication to something that’s not immediately obvious. When you look at a poster weaving, it’s not clear why a person would go to that length to make it. I think that question mark is a good one.

Do the brands whose posters you use ever reach out?

It’s happened twice. Both with music posters. In the first case, a Swedish band did a poster in Berlin with a Japanese painter’s image on it, and I heard from both the musicians and the artist, who both thought it was cool. Another time, I was working with posters for a Leon Bridges album. The album designer saw it, and he loved what I’d made. Those have not evolved into any ongoing collaborations, but the kudos are nice.

I would fear a different reaction, since you’re not exactly removing these posters in an archival manner.

Not at all. I’m pulling down paper covered in glue and glued to other paper. I only have so much control. But whenever there’s an imperfection, that ends up being a significant part of the final piece. It’s almost frustrating when I have a full one, because you’ve got to have tension.

You could make those shapes artificially, here in your studio. Just tear a poster in half before you start weaving it. Don’t tell anyone.

But it would never look as good as a rip that occurred on the street. I couldn’t do those on my own if I wanted to. They would be bad.

RJ Rushmore is a writer, curator and public art advocate. He is the founder of the street art blog Vandalog and culture-jamming campaign Art in Ad Places. As a curator, he has collaborated with Poster House, Mural Arts Philadelphia, The L.I.S.A. Project NYC and Haverford College. Rushmore’s writing has appeared in Hyperallergic, Juxtapoz, Complex and numerous books. He holds a B.A. in Political Science from Haverford College, where his thesis investigated controversies in public art.

This story is part of a partnership between The Philadelphia Citizen and Forman Arts Initiative to highlight creatives in every neighborhood in Philadelphia. It will run on both The Citizen and FAI’s websites.

This story is part of a partnership between The Philadelphia Citizen and Forman Arts Initiative to highlight creatives in every neighborhood in Philadelphia. It will run on both The Citizen and FAI’s websites.

![]() MORE FROM OUR ART FOR CHANGE SERIES

MORE FROM OUR ART FOR CHANGE SERIES