[Editors note: This is part of an occasional series that will feature students from Buzz Bissinger’s class, as well as Kelly Writers House at Penn.]

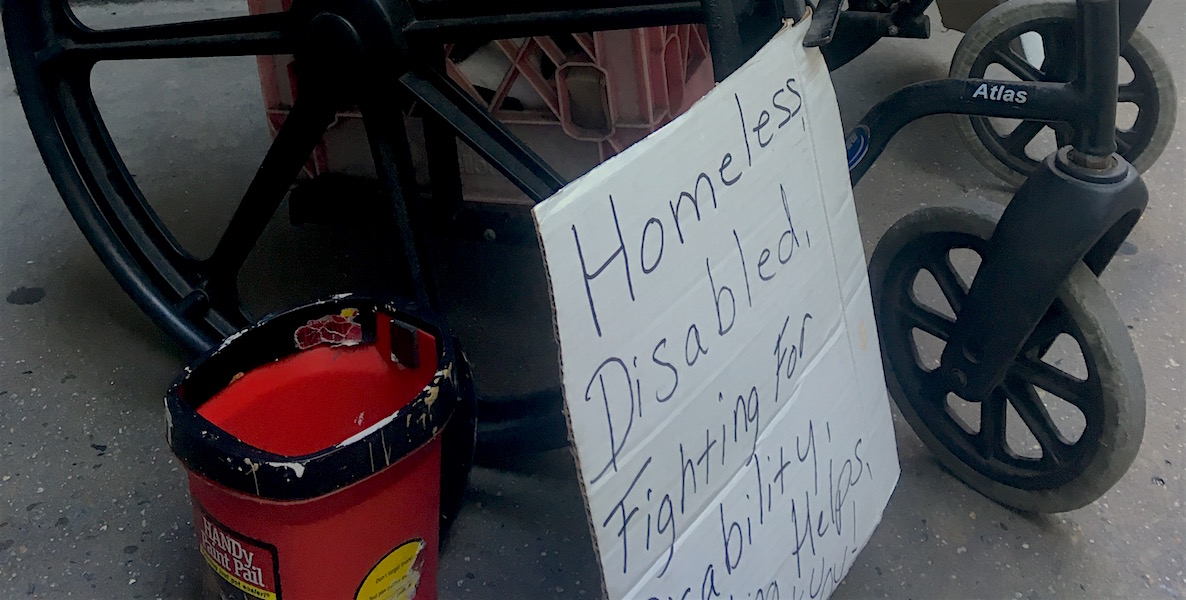

In an alcove on the eastern face of Philadelphia’s City Hall, four unseen eyes peer out from their wind-protected corner at the slow trickle of tourists meandering from the Marriott to Macy’s. Robert Hicks and Anna Harvey sit side by side and watch the sightseers see the sights– the wide eyes lifting to the vaulted porticos of the Masonic Temple, the twinkling lights just visible through the closed gates of City Hall, the winter accoutrements of fellow passersby—looking at anything but the detached prosthetic leg, or the cardboard sign next to it.

Homeless,

Disabled,

Fighting For

Disability,

Anything Helps,

Thank You!

As the Founder’s Bell rings out the last stroke of nine, Robert and Anna realize they will be locked out of City Hall for the sixth day in a row. The two usually station themselves in the eastern archway leading into the central courtyard, where a steady stream of foot traffic passes through en route to Dilworth Park, in front of City Hall, or 15th Street station below it. Now a 51 foot Christmas tree sits in their spot, waiting for the annual tree lighting ceremony after Thanksgiving.

City workers closed the gates on Tuesday to trim the courtyard with glowing ornaments and string lights. Now it’s Saturday, and though the decorations are finished and the crew nowhere in sight, two sets of elaborate black-steel gates still surround the courtyard. Until they reopen, Robert and Anna have been relegated to a doorway nook on the City Hall’s quiet east side. The HANDy paint pail fitted into the hollow top of Robert’s prosthetic leg has only collected $2 today.

Robert and Anna are two of more than 5,600 Philadelphians experiencing homelessness while the rest of the city is caught up in the glorious frenzy of the holiday season; two of 1,000 who sleep on the streets. Aside from the constant jingle of Salvation Army bells and the few extra dollars from those “seasonal givers” who only see the poor in December, nothing changes for Robert and Anna at Christmas. To most they are the unsightly outdoor furniture of an otherwise chic and thriving Center City. They are less than invisible: they are wanted invisible.

Anna pushes herself up from the blanket-covered office chair that serves as her seat, suitcase, and bed, and leans hard on a green metal cane. She nods at Robert, he nods back, and she shuffles her husky frame toward the nearest Wawa for her daily indulgence of caffeine, warmth and hygiene. Two kitten-heeled city employees hurry past Anna’s chair into City Hall with a hasty “good morning.” Robert apologizes for being in the way.

A woman flanked with shopping bags speeds past on a motorized wheelchair, and Robert’s eyes follow her down the sidewalk. His own wheelchair is a “replacement,” swiped from outside Penn Presbyterian Hospital when the lawn-mower wheels on his first, makeshift wheelchair started to crack. “It was an upgrade,” he chuckles. “A trade-up.”

Robert and Anna are two of more than 5,600 Philadelphians experiencing homelessness, two of 1,000 who sleep on the streets. To most they are the unsightly outdoor furniture of an otherwise chic and thriving Center City. They are less than invisible: they are wanted invisible.

Robert was an able-bodied home and business owner until August 30, 2016, when he took a day off from running his roofing business to volunteer with Habitat for Humanity, a nonprofit that builds homes for families in need. While he was on the roof, “a helper, a young kid, moved the ladder, and didn’t put it back properly.”

He fell sixteen feet, shattering both wrists and compound-fracturing his ankle. In March, after a series of grave infections that culminated in amputation, he left the hospital with no leg, no livelihood, and no place to go. Temporary housing quickly drained his savings, and he became homeless in July at age 51. Now on the eve of his first winter on the streets of Philadelphia, Robert is fighting to secure worker’s compensation and disability benefits “before my stump freezes off.”

One of the kitten-heeled ladies pops her head back out of the door and offers to order him something from her Dunkin’ Donuts app. He thanks her; requests a coffee and apple fritter. “Alright, comin’ right up. It’ll be under Jackie H.”

Robert peels back the three layers of pants covering his amputated right leg. Removing the collection pail, he fits his half-leg into the prosthetic. It is a few inches too short, turning the one-block walk to Dunkin’ Donuts into a syncopated hobble.

It’s 9:41, and Anna still hasn’t returned from Wawa. Robert considers calling her with the phones they received through the SafeLink program, but knows this is the only hour of the day she gets time for herself, indoors and alone, albeit among the throng of coffee- and condom-seeking Philadelphians. Anna is a woman of ritual: Each morning she washes herself at the restroom sink, buys herself a coffee, then sits at the little counter by the window and watches the pedestrians go by on Walnut Street. Robert never joins her; he tries to stay outside whenever possible. “Once you get used to it, you almost don’t want to go inside, ‘cause then you’ll get used to the warm and get even colder when you go back out.”

A plump brown sparrow hops toward Robert and his apple fritter. No salvageable crumbs in sight, it skitters away to join a few others perched on the rim of the nearest garbage can, taking turns dive-bombing. Robert rests his coffee in his prosthetic and watches it go.

“Where you goin’, little bird?”

At 10, Robert spots Anna slowly returning from her morning break. Two pairs of pants, three shirts, and two jackets make her look topheavy. The outermost layer, an olive green coat with pink flowers embroidered onto the edges, “was a found, believe it or not!” It hung for a whole day in the City Hall women’s restroom before Anna picked it up. Inching along Juniper Street, hunched over with cane in hand, she seems older than her 40 years. Her double chin makes her appear, from a distance, to always be smiling.

Anna’s troubles began in Green Bay, Wisconsin, after a childhood spent “bouncing around the Midwest.” At age 17, she was hit by a speeding car and, after a brief flight through the air, landed on the back of her head. If she had not blacked out in midair, relaxing her body, the impact could have paralyzed her for life. Instead Anna was left with brain damage—a Chiari malformation of the cerebellum—and major muscle spasms that are progressively collapsing her back.

Despite her injuries, she graduated from high school a year later in 1995, and got jobs in fast food, then bartending, hostessing, and finally short-order cooking, which she loved. She had completed job core training and a some college courses at Kirkwood Community College before the effects of the accident caught up to her.

Anna says that “what makes it harder to live on the streets is being a woman—not the disabilities.” She has been repeatedly approached for sex, threatened with rape, groped, and, once, given a bone-bruising blow in the face for refusing. In October Anna asked if they could stick together. “We literally watch each other’s backs.”

In 2000 she was put on disability benefits for manic depression related to the Chiari malformation, but worked on and off until a surgery slowed her down further. She finally left Iowa —and an abusive mother—in 2008, and moved to Maine, then to Tennessee, Florida, and Louisiana doing odd work and meeting odd people, then to Maine again, where she became homeless for the first time when rent prices rose above her monthly disability check. After a few months she was invited to stay with a friend in Reading, Pennsylvania. When that friend became a lover and then an ex-lover, Anna found herself alone again, on the streets of Philadelphia.

She will need a wheelchair soon; “I’m not sure how much longer I’ll walk.” And though she retains an impressive vocabulary, she now speaks slowly and with great effort, taking long pauses to remember things exactly right. She receives disability benefits for manic depression related to the Chiari malformation, but it is her physical disabilities that are worsening rapidly.

Still, Anna says that “what makes it harder to live on the streets is being a woman—not the disabilities.” During her time in Philadelphia she has been repeatedly approached for sex, threatened with rape, groped, and, once, given a bone-bruising blow in the face for refusing. After this last incident, Robert, then just an acquaintance, told her “if you ever have issues like that again, you just give a yell.” The threats and requests didn’t stop, and in October Anna asked if they could stick together. “We literally watch each other’s backs.”

Anna finally arrives at City Hall, having taken a detour to pick up a money order for Robert’s replacement ID. Last week, just after receiving his birth certificate, Social Security card, and Pennsylvania Identification Card, Robert’s wallet disappeared. His wallet has been stolen twice before, but he doesn’t want to assume someone took it—especially since Anna would be the most likely suspect. For now he operates under the assumption that it fell out of his pocket when he hopped too quickly across the street, “my version of running.” He thanks Anna, re-attaches the prosthetic, and starts the one-mile marathon to the Department of Motor Vehicles on 8th and Arch streets.

Halfway through Chinatown his pace begins to slow. Every other step forces the amputated surface of his leg down into the hard plastic prosthetic, and the cold only aggravates the pain. His doctor cut off his Percocet prescription in July, when “they accused me of abusing, which I was.” Robert was taking six instead of the prescribed four 20 mg pills per day. “When you go through the emotional trauma of losing a limb and your living, it’s hard not to try ‘n’ take the edge off.”

Months went by without pain management, colder and colder, until Robert started to buy pills from a friend, Chris, who has a prescription for 20 mg Percocets that he doesn’t need. Their most recent transaction caused “a little run-in” with the police. Chris was arrested on an unrelated warrant; Robert was told to go home.

By the last block before the DMV Robert stops every 10 feet to balance on his good leg and scowl at his stump. Should’ve just brought the damn chair. Finally reaching the front door, he reaches to pull the handle, then stops.

Veteran’s Day

Saturday, November 11th, 2017

CLOSED

“Veteran’s Day was yesterday!” Robert groans and rubs his balding head with both palms. It is Veteran’s Day, but since federal government offices observed the holiday on Friday, he thought the DMV would follow suit. “I was here just a few days ago and that sign wasn’t here.” He won’t get an ID until Tuesday, when the DMV reopens, which means he can’t apply for a Social Security card until after that. After trying in vain to peer inside the shaded, tinted windows, Robert turns around and starts the journey back to City Hall.

On cold days like today he can feel the titanium plates in his head and forearm. Robert spent most of his 20s and 30s in Florida, alternating between construction work and racing for the National Hot Rod Association. His speed and daring on the track was just beginning to earn him some enviable sponsors—Goodyear, Tire Kingdom—when his dragster spun out at maximum speed and crashed onto the asphalt, smashing his skull, pelvis, femur and collarbone. He doesn’t regret a minute of his drag racing career. “Ain’t nothing like it.”

Robert all but drags his leg the final few blocks back to City Hall. He shuffles slowly, unevenly, keeping his head down in a long-term grimace while pedestrians hurry around him on both sides. Just before the last intersection, still just out of Anna’s sight, he ducks into the 13th Street SEPTA station. He returns an hour later with a new spring in his step. He tells Anna about the DMV fiasco, and, when pressed, about the rest of his afternoon.

“I went to see my friend who is a quadriplegic… he was thrown from a moving vehicle and broke his spine.” He anticipates her unsaid question. “Why I went to see him? Don’t really want to get into that, but it has to do with what I told you before with Chris.” His hand fumbles with something that rattles in his left coat pocket.

Anna is interested, but has more pressing news. While Robert was gone, a cleaning lady told her that the west arch of City Hall would be opened so that visitors to Dilworth Park could access the restrooms, every weekend from now through February. Normally the restrooms are only open when City Hall is open, from eight to five on weekdays. On evenings and weekends Robert and Anna would have to ask a begrudging employee to let them into the bathroom at Starbucks or McDonald’s. Things started to get better once Anna memorized a few restroom keycodes, but weekend access to the City Hall bathrooms is a game changer.

More importantly, the opening of the west arch means a better place to stake out—shelter from the wind, more pedestrians, and the potential to make a few extra bucks. “Arright!” Robert declares, packing up his sign, chair, and cart with unusual energy. “We’re movin’!”

Anna piles a large black duffel bag, purple duffel bag, sparkly purple backpack, and miscellaneous odds and ends onto the seat of her office chair, then tucks the hanging ends of the blankets between the bags to keep them off of the ground. She pushes the whole ensemble forward from behind, leaning on the chair’s back instead of her cane.

![]()

Robert removes his prosthetic, placing it and his signs into the white rolling cart where he keeps his bedding. He scoots the wheelchair backward with his good leg, dragging the cart behind him, looking over his shoulder to see where he’s going. The pair roll slowly from City Hall’s desolate east side, around the south side and past the Ritz-Carlton to the west, where the Christmas season has begun in Dilworth Park. A lush array of winter foliage is arranged into a perfectly-trimmed garden maze, decked in white string lights and rustic log accents. Topiary reindeer hold signs announcing to passersby that Philadelphia is #AmericasGardenCapital. Young women in fur-lined coats pose for endless Instagram photos under the central pergola.

The little caravan passes a group of city workers in fluorescent vests erecting tents for the Made in Philadelphia Holiday Market, each tent topped with a glowing Moravian star. Soon tourists will flock here to purchase seven-dollar all-natural dog treats shaped like candy canes, and fifteen-dollar jars of Bacon Jam.

Robert and Anna run into some trouble rolling their loads over the large cable protectors that zigzag across the path toward City Hall. They proceed one at a time, slowly rolling up, across, and down the tiny slopes, careful to keep everything upright. A few weeks before, Robert traveled too fast over a curb and fell backward, smacking his head on the asphalt.

Turning the corner, they pass the Rothman Ice Rink—the centerpiece of Dilworth Park’s Wintergarden—whirling with colorful coats and runny noses. At $15 for admission and skates, there are more shivering spectators than skaters under the starry string-light canopy.

Robert and Anna roll into the cavernous west arch of City Hall. They take turns using the restroom, then set up camp on opposite sides of the hall. Robert fishes the prosthetic leg out of his cart and sets it in front of him, fitting the HANDy paint pail inside with an American flag for good measure. With the inner gates leading to the central courtyard still closed, there will be no through traffic, but sympathetic bathroom-goers might spare some change. It is three in the afternoon; still a few hours to make a buck before sunset.

Now comes the waiting game. Anna nestles deep into her office chair and produces a science fiction novel from one of its folds. Both she and Robert are avid readers, and buy 25 cent books from the Free Library’s sale shelf whenever they have a quarter to spare. Anna reads sci-fi and fantasy to escape the cold gray of the streets, but Robert chooses realistic, crime-ridden books with an eye toward writing his own someday.

He could write about “when I killed a man at age nine:” Young Robert witnessed a motorcyclist crash and fall into a ditch face down, drowning. He ran over and tried to pull the man’s face out of the water, not knowing that his neck was broken. “He would’ve died if I left him, but when I turned him over, he died in my lap.”

Robert was an able-bodied home and business owner until August 30, 2016, when he took a day off from running his roofing business to volunteer with Habitat for Humanity. While he was on the roof, “a helper, a young kid, moved the ladder, and didn’t put it back properly.”

He could write about shooting his stepfather two years later—when he got off the school bus, he could hear his stepfather beating his mother. She was unconscious by the time Robert got inside, so he ran to find his stepfather’s shotgun and shot him in the shoulder. He saved his mother’s life, but paid dearly for it months later: His stepfather forced him to stand still while he poured gunpowder into his hands and lit it on fire, burning Robert’s eleven-year-old skin to a molten crisp.

He could write about his two stints in state prison, “for stupid shit” like driving with a suspended license, or his final drag race, or his job working on Sylvester Stallone’s Miami home. But Robert is sure all this would have to be a fiction adaptation. “I could do it in a nonfiction way, but there’s no way you’d believe this shit.”

Outside the arch, a recorded announcement asks skaters to vacate the ice rink so it can be resurfaced. Tots lean on penguin-shaped skate aids and waddle toward the exit. Some guests watch the Flyers zamboni give the ice a mesmerizing sheen, and others take a bathroom break, passing Robert and Anna to enter City Hall. Mothers reflexively touch their children’s shoulders as they walk by, making sure they don’t wander too close to the dirty people and their hoards.

A middle-aged man drops a five-dollar bill into Robert’s paint pail.

“Thank you for your service.”

Robert nods and smiles, but says nothing until the man is out of earshot. “A lot of people mistake me for a vet because of the leg, but I’ll tell ‘em the truth if I can’t duck the question somehow. If I put ‘disabled vet’ on my sign it’d be a felony. But,” he shrugs, “I can have as many American flags as I want.”

Two matronly church ladies in long skirts and furry boots stop by, handing Anna and Robert each a large bag made out of T-shirt material. They share a pleasant exchange about the unpleasant weather, and Robert thanks them as they leave. Inside each bag is a mat made out of woven grocery bags, a sandwich, and a list of thirty-nine shelters and meal programs.

Anna scans the list. “It doesn’t list the times they’re open…They won’t let you in if you come at the wrong time, so you really need the times on there.”

Robert looks closer at the page. “Some of these I haven’t been. Some of them I highly recommend. Some of them, don’t go there unless you’re armed.”

Soon after he became homeless, Robert went to Our Brothers’ Place, an all-men’s shelter on Hamilton Street. He stayed for two nights, but after seeing used condoms accumulate on the bathroom floor, he decided it might be safer to leave. He moved on to Sunday Breakfast, another men’s shelter not far from City Hall. Upon arrival he was asked to place all valuable belongings into a safe—which was promptly robbed by a rogue employee. Anna was robbed while staying at a women’s shelter on 49th Street.

Now neither wants to take the risk, opting instead to lay their blankets on below-freezing concrete and fall asleep to the blaring lullaby of Market Street.

A few young families trickle in from the garden maze and peer through the gate at the Christmas lights illuminating the courtyard. Finding the gate locked, they about-face and stroll back out to the park. The children stare at Robert and Anna as they are pulled past, but the adults have mastered the art of not seeing. A woman in a plum peacoat smiles at Robert. He smiles back before realizing that hers was only a “leftover smile,” meant for the older woman walking beside her.

As the sun dips lower in the sky, the waiting game becomes the warmth game. The exhausting trek to the DMV warmed Robert temporarily, but now the cooled sweat has left him damp and wind-chilled. Four outdoor space heaters beckon to him from beside the ice rink, but they are within the enclosure reserved for paying skaters. Anna puts her book down and sits on her hands to keep them warm; Robert begins to doze off in his chair. The American flag on his prosthetic leg waves in the bitter wind.

The sun sets at 4:48 PM, and Robert and Anna once again pack up wheelchair, cart and office chair to find a place to sleep for the night. Yesterday they came across a quiet hallway in the depths of 13th Street station, and stayed there instead of trying to sleep outside in subfreezing temperatures and 16 mile per hour winds. They accidentally slept in front of the police substation, and were told to move in the middle of the night, but eventually settled in an abandoned concourse which was at least fifteen degrees warmer than outside. The concourse is only accessible on weekends because of construction nearby, but Robert figures they’ll sleep there until someone kicks them out.

Anna goes to the restroom one last time before they head underground. She runs the hot tap over her hands until they are red and throbbing, then puts them under the hand dryer for another three minutes.

![]()

The caravan rolls out again: Anna nearly hidden behind her precarious rolling stack, Robert scooting backwards through traffic, dragging his leg and cart behind him, across the street and into the station. A shriveled man in a shredded brown coat leans over the railing in the entrance and cackles frantically, baring his sparse teeth.

Robert and Anna squeeze their belongings into the station’s elevator—lucky, since nearly half of the Broad Street Line stations are not wheelchair accessible. They pass the platform and roll down a sloping, twisting path of dilapidated tunnels. Robert rolls fast down one of the ramps, curving in fancy twists and popping a wheelie. Another resident of the tunnels, sitting next to his own wheelchair, grins at Robert’s backward stunts.

Turning off the main concourse, they arrive at the dead-end corner that will be their bedroom. To one side is a hundred feet of DANGER tape and, further on, a chain-link fence surrounding the beginnings of a construction site for the Center City Concourse Improvement Project. A plastic bottle of tobacco spit leans on the near end of the fence.

On the opposite side of the dead end, cracked once-white flooring abruptly gives way to a black-and-white diamond patterned granite tile, then to the the pristine revolving doors of the Wanamaker Building’s office entrance.

Robert straps on his prosthetic and stands up to dig around in his cart. He emerges with the bottom layer of his bed, a large plastic poster advertising the latest season of Gold Rush, a Discovery Channel reality show. Sweeping away some cigarette butts he rolls the poster out on the ground next to Anna, then the trash-bag mat the church ladies gave him, then eleven more blankets on top of the mat. It is 5:15: nearly time to sleep if he wants to be up before dawn, but not quite. He rolls around the corner in search of an outlet.

Anna wheels her chair to the very corner of the dead end. She piles the black duffel, purple duffel, purple backpack in front of the office chair as a makeshift ottoman. Sitting in the chair with her legs on the pile, she drapes three blankets over herself and starts back in on her reading.

The jingle of keys approaches from the main concourse, and Anna startles. Discovery by a Transit Police officer or a SEPTA employee could force them to to hide elsewhere in the tunnels—or out into the cold. The jingling stops, and muffled voices come from around the corner where Robert has stopped to charge his phone. After a few minutes a blue-clad SEPTA employee flashes in and out of sight, fast-walking back to the main concourse. Robert slowly rolls around the corner and back into the dead end.

Every other step forces the amputated surface of his leg down into the hard plastic prosthetic, and the cold only aggravates the pain. His doctor cut off his Percocet prescription in July, when “they accused me of abusing, which I was. When you go through the emotional trauma of losing a limb and your living, it’s hard not to try ‘n’ take the edge off.”

“That was the head guy from the maintenance crew,” he explains. Having just returned from serving in the military five weeks prior, the man saw Robert’s leg and assumed he too was a veteran. “He said, ‘Don’t worry about it. If you guys need anything, my office is right over there.’” Relieved, Robert takes off his outer layer of pants, three outermost shirts, and two outer pairs of socks, folding them neatly on the seat of his wheelchair. He places the coin bucket in the leg, leg behind the cart, cart behind the wheelchair.

Suddenly Robert clutches his head. Tiny zigzag lines appear in his vision, swimming back and forth as his head begins to throb. “Migraine,” he mumbles. Anna rummages around in her purple backpack until she finds two Tylenol. Robert takes them quickly. “Cigarette smoke does that to me.”

As the night outside gets colder, other people have descended into the station to smoke. Now the whole underground is permeated with throat-burning tobacco fumes. Even without the smoke the station is the perfect place for a migraine: thick dust, glaring fluorescent lights, the roar of the Market-Frankford train. Robert downs a leftover ham sandwich and diet coke, and, when that doesn’t help, produces a small bag of graysish pills from his coat pocket. After a few minutes the pain starts to subside.

“Hopefully this is the last day I have to worry about that,” he says, covering his eyes to block out the light. He says he should have received a check for $8,200—one-third of his worker’s compensation after legal fees—several days ago. “They had 30 days to give me my money, and their 30 days is up.”

As soon as he gets the check from his lawyer he plans to open a bank account and find a place to stay for himself and Anna, who for the last several months has been helping him with her disability checks. But worker’s compensation is nothing compared to the case for the loss of his leg. According to his lawyer, Robert says, the projected settlement from Habitat for Humanity is $250,000 in a lump sum, plus $500 for the next 500 weeks.He could be a rich man, but not yet.He has already found a house in Germantown that he wants to buy, flip, and sell; he wants to visit his mother and take her on one last road trip before stage three kidney failure takes her home; he wants to see his children for the first time since his wife died of accidental overdose; he wants to spoil his grandbabies.

But for now he covers himself with 11 grimy blankets and tries to get some rest. Anna turns her face toward the corner and pulls her stocking cap down over her eyes. Facing them through the DANGER tape are the faded murals of the old concourse: vague, sketch-like collages of the Continental Congress, the Mummers Parade, the Clothespin statue, Betsy Ross. The floor-to-ceiling face of Benjamin Franklin looks down upon the dead end from the farthest panel, the mural’s name scribbled onto his lapel: “Philadelphia, then and now.”