For decades, the Detroit neighborhood known as Fitzgerald was, like so many Philly neighborhoods, an example of urban disinvestment and neglect. In 2016, some 30 percent of buildings and lots were abandoned. Home prices were too low even for owners to get loans to fix them up. Many streets didn’t connect to each other. Park space consisted of one small, run-down playground. The commercial corridor lacked the kind of small businesses that provide vibrancy and economic strength to city neighborhoods.

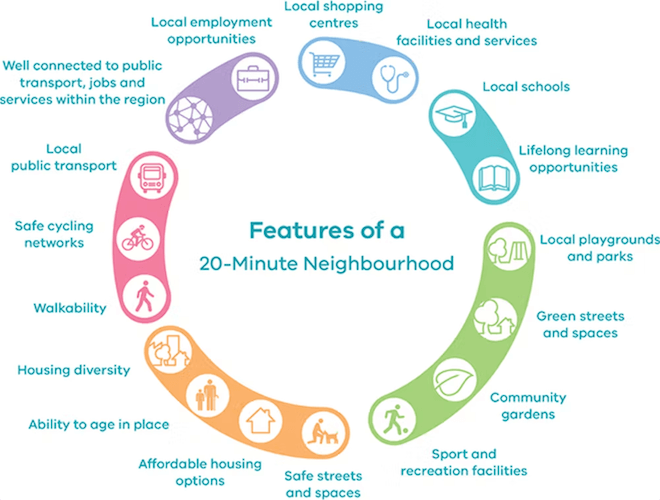

In 2016, Mayor Mike Duggan made Fitzgerald the centerpiece of a plan that he vowed will bring Detroiters within 20 minutes by foot or bike from retail, transit and parks — and also free from blight, including abandoned buildings and crumbling infrastructure. That made Detroit one of several cities around the globe — including Paris, Portland and Houston — to make a deliberate effort to create what is known as a 15-Minute City or 20-Minute Neighborhood, in which all of a resident’s non-work needs can be reached within a few minutes without needing a car.

Duggan’s Fitzgerald Revitalization plan included renovating more than 100 homes with federal affordable housing funds; building a greenway through vacant lots; turning lots into meadows or orchards; renovating apartment buildings in part to use as affordable student housing; improving streetscapes; adding protected bike lanes; and adding retail in nearby commercial corridors.

Today, there is much work still to be done in Fitzgerald. But the commitment to a 20-Minute Neighborhood there has already had far-reaching impacts.

- Home values have risen.

- A beautiful new green space, Ella Fitzgerald Park, was built on top of 19 vacant lots in the middle of the neighborhood.

- A walking and biking greenway connects cross streets, making it far easier to access different points in the area.

- A concerted effort to revitalize the commercial corridor has brought improved streetscapes, investments in small businesses and a city-operated storefront called HomeBase that is a community center and provides access to city services.

Six years later, well after the hype of Duggan’s announcement has died down, the city, residents and private investors are continuing to carry out the mayor’s vision and to learn from the effort.

“The key to sustained community improvement is a lot of small steps that add up to a better whole,” says Ben Bryant, senior associate at Philly’s Interface Studio, which, through the group Reimagining the Civic Commons, is helping to evaluate the efforts in Fitzgerald. “Some things that happen quickly — like the park — can build momentum and build trust. If you think the trajectory of your neighborhood is going to improve, it takes a lot of the stress off, and makes you want to work on your neighborhood more.” That, then, becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

An idea as old as cities themselves

Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo — a hero of sustainable urban living — is credited with popularizing the idea of the 15-Minute City, which was the cornerstone of her reelection campaign in 2020. This came after her earlier move to ban cars from Paris’s city center and dramatically increase bike lanes as a way to curb pollution and congestion in the city.

More recently, an effort in Sweden has pushed for a 1-minute city, aiming to transform each block in the country according to the needs of the residents so that “every street in Sweden is healthy, sustainable and vibrant” by 2030, according to Street Moves, which initiated the project. So far, four cities — Gothenburg, Helsingborg, Umeå and Stockholm — are taking part.

“The key to sustained community improvement is a lot of small steps that add up to a better whole,” says Ben Bryant, senior associate at Philly’s Interface Studio. “If you think the trajectory of your neighborhood is going to improve, it takes a lot of the stress off, and makes you want to work on your neighborhood more.”

But really, the idea is as old as cities themselves. Before the over-prevalence of cars, city neighborhoods provided everything to their residents: The density of housing, businesses, services (and even jobs!) was a fundamental feature of urban living, out of necessity as much as anything else.

That changed because of many of the same issues that plague Philadelphia today: the decline of manufacturing jobs near where people live; redlining and subsequent disinvestment in neighborhoods outside of Center City; unaddressed blight; the disappearance of grocery stores and other businesses that provide healthy options for residents in the surrounding community; inequities in health care and city services.

Urbanist Bruce Katz, founding director of Drexel University’s Nowak Metro Finance Lab, set the scene in a column The Citizen ran a couple years ago:

Many urban neighborhoods — particularly those that were targets of urban renewal in the 1950s or victims of highway expansion in subsequent decades (i.e., more appropriately labeled “urban devastation”) — bear a common spatial reality, irrespective of the city in which they are located. Once thriving commercial corners or corridors are now populated by abandoned buildings and vacant lots (often owned by various arms of the city government or local churches or absentee slumlords in various stages of tax delinquency). This is true even when nodes of economic strength (a university or hospital or publicly subsidized sports complex) are, incredibly, located only a few blocks away.

These neighborhoods are past and present victims of institutional racism. They literally sit on the “wrong side of the color line;” access to quality capital and mentoring to help residents purchase homes and build businesses remains scarce while parasitic capital for dollar stores, payday lenders and check cashers is plentiful. The result: While the poorest 10 percent of American families have gone from having no wealth on average in 1963 to being $1,000 in debt in 2016, large companies omnipresent in poor neighborhoods (like Dollar Tree, which earned $22.8 billion in revenue in fiscal year 2018) have thrived.

In the United States, cities have started to push back against this dystopia, in some cases for reasons our forebears never even considered. In 2010, Portland, Oregon, released a Climate Action Plan whose cornerstone is cutting down on car emissions by creating 20-Minute Neighborhoods that allow 90 percent of residents by 2030 to walk or bike to all of their daily needs, excluding jobs. That project started with a dive into the data, which produced a map not dissimilar to what Philly’s would look like, with areas in and near its city center already established with services walkable to most residents.

Philadelphia is, theoretically anyway, already on board with this idea. In 2020, the C40 network of mayors and cities collaborating to combat climate change — which includes Philadelphia and Mayor Kenney — issued a policy agenda that included the creation of 15-Minute Cities, as a way to cut down on the carbon emissions associated with driving. Since then, traffic in Philly has gotten worse, not better.

A survey of residents using the new park has already borne that out. In 2016, only 34 percent of Fitzgerald residents thought the neighborhood had changed for the better in the last few years; in 2018, after the park was built, 89 percent of those using it said the neighborhood had improved.

We are also a city with a 25 percent extreme poverty rate, low tax base, serious gun violence problem, long history of neighborhood neglect, and councilmanic prerogative, which creates different rules for different neighborhoods. Even potentially good ideas — the Land Bank, a community-focused Sixers stadium in Center City, making Washington Avenue safer for children — lose their way here, amidst political jockeying and the reality of economic hardship. That makes us different from Paris and Portland — though not so much from Detroit.

In Detroit, Duggan used a combination of philanthropic, federal, state and local governmental funds and private investment to create and execute a plan that meets the needs of Fitzgerald residents. Bryant and Interface got involved through Reimagining Civic Commons, a philanthropy-funded effort to design and operate public spaces in a way that delivers social, economic and environmental benefits for their communities. (Reimagining Civic Commons piloted in Philadelphia in 2015.)

Interface did an initial survey of residents to track the engagement, feelings and economic situation in the neighborhood; a follow-up is set for this year. Already, Bryant says the park has brought more residents outside and enjoying the neighborhood, and he predicts another improvement: Residents’ perceptions of their own community.

In fact, a survey of residents using the new park has already borne that out. In 2016, only 34 percent of Fitzgerald residents thought the neighborhood had changed for the better in the last few years; in 2018, after the park was built, 89 percent of those using it said the neighborhood had improved.

Developer David Alade, who rehabbed several Fitzgerald houses, told Detour Detroiter earlier this year:

When we started investing in this neighborhood and laid out our vision to folks, they couldn’t believe that a house could sell for even $60,000. They’d been there 40 to 50 years, seen the best of what the neighborhood could be when there was no vacancy, filled with families and children. They had this positive image of the neighborhood and still struggled to imagine it returning to that status. To go from that uncertainty to homes selling for over $100,000, from feeling pessimistic to feeling inspired and wanting to own equity in that neighborhood, so they could sell or get a reappraisal or rent it to family. I’m really proud of that transformation. That didn’t happen overnight — it couldn’t happen overnight. It took time and it took intention.

Is Philly at the right time and in the right place?

Philadelphia is in some ways the ideal place for enacting a 15 or 20-Minute City. “It’s a great strategy for dense older cities like Philadelphia, which wasn’t built around the car — it was built around walking and public transit,” Bryant says.

And now is in at least one way the ideal time to be deliberate about forming neighborhoods that are pocket cities: Last year, the city’s planning department started work on Philly’s new Comprehensive Plan, the far-reaching document that lays out citywide and neighborhood goals and is supposed to guide every decision around housing, employment, transportation, parks and other aspects of the physical environment in every neighborhood. Framing that plan through the lens of a 15- or 20-Minute City could be transformational. It could focus efforts from different departments, from Commerce and Streets, to Parks and Recreation and public health, towards the goal of a more livable city for all.

There are many piecemeal examples of 20-minute neighborhoods already in Philly. Bryant’s (and my) neighborhood in South Philly, for example, is a bonanza of urban pedestrian living. East Passyunk has three (soon to be four) grocery stores; a produce stand; three city parks and rec centers; several doctors offices, including primary care, pediatrics, eye doctors and dentists; a library; subway and bus routes; small retail, several restaurants, music venues and fitness studios; public, charter and parochial schools; daycare centers; a bike route into Center City.

Some of that happened organically, but it was also boosted by deliberate planning, like a civic association that helps young businesses secure low startup rents, and a public-private partnership led by Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia to tear down and then rebuild a park, library and rec center, with doctors offices above it.

Before the over-prevalence of cars, city neighborhoods provided everything to their residents; the density of housing, businesses, services (and even jobs!) was a fundamental feature of urban living, out of necessity as much as anything else. That changed because of many of the same issues that plague Philadelphia today.

On the other side of Center City, the Sharswood neighborhood north of Girard College is in the midst of executing its Sharswood Blumberg Transformation Plan, launched by the Philadelphia Housing Authority as part of the federal Choice Program in 2015, to rethink housing, health, education and employment on the site (and surrounding streets) of a former public housing high rise. In 2020, PHA received a $30 million grant to implement the plan, which includes 600 units of housing, renovating the neighborhood Peace Park and shopping center, creating a small business incubator and providing other job training.

Or, consider the work Shift Capital is doing in Kensington — against the odds — to revive the neighborhood’s commercial district, along with building mixed housing and light manufacturing facilities.

What do all of these projects have in common? Cross-sector collaboration, community engagement, creative funding sources and the vision to imagine cities as they are supposed to work, for everyone. As Alade said of the work in Detroit: “It took time and it took intention.”

WHAT YOU CAN DO TO MAKE OUR NEIGHBORHOODS BETTER

MOST POPULAR ON THE CITIZEN