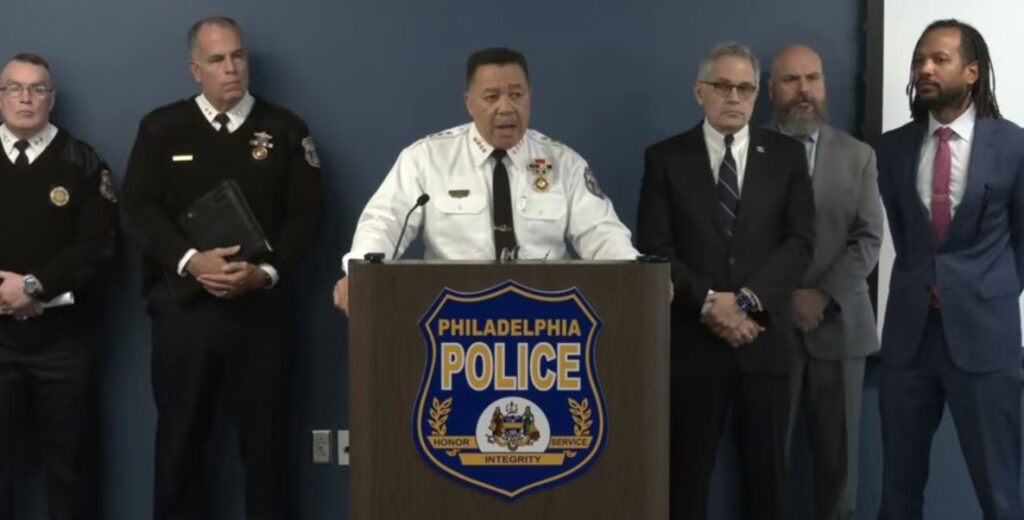

On Tuesday, January 30, four days after a fatal police shooting in North Philadelphia, Commissioner Kevin Bethel held a press conference that felt unlike anything we’ve seen much of in Philadelphia of late. Bethel stood at the podium surrounded by half a dozen people. On one side of him: uniformed police officials. On the other: District Attorney Larry Krasner, front and center, with a couple of his staff members behind him.

Bethel and Krasner each took turns at the podium — not to spar, as the DA has often done with the police during (and before) his tenure. They were there, together, to call for patience from Philadelphians while both departments investigated the shooting. They both promised accountability. And they both vowed a commitment to transparency.

To that end, they released to the public a five-minute, slightly annotated video of the encounter that led to 33-year-old Andrew Spencer’s death at the hands of Philadelphia Police Officer Raheem Hall.

“Our goal is to be transparent in this work,” Bethel said shortly before playing the video. “Our goal is to hold ourselves accountable for how we operate in this space. You can see by the partners up here.”

As Inquirer columnist Helen Ubiñas pointed out this week, Bethel ended the press conference without taking any questions from the reporters in the room — something she said casts doubt on his claims of transparency. On the other hand, as Ubiñas also noted: There is only so much officials can say while an investigation is ongoing. And, this did not feel like the same old covering up — or stumbling around — that we’ve too often seen from law enforcement.

Compare this, for example, to what happened last August after Officer Mark Dial shot and killed Eddie Irizarry in his car five seconds into a traffic stop. In the immediate aftermath, police claimed that Irizzary had lunged at them with a knife, prompting Dial to shoot him several times. That was a lie.

Actually, Irizarry was sitting in his car, with the windows closed, when Dial opened fire — a fact made clear pretty quick by a bystander video. Within days, Commissioner Danielle Outlaw was forced to take back the initial reports. She fired Dial for insubordination — and then herself stepped down from her job shortly after.

Meanwhile, Irizarry’s family released video of the encounter from nearby surveillance cameras — and three weeks after the shooting, District Attorney Larry Krasner, in announcing murder charges against Dial, publicly released the cops’ body camera footage in a press conference held by his office, with only his staff present.

It’s early days still for Mayor Parker’s newly-appointed Commissioner Bethel, but could this episode be a harbinger of a new day for law enforcement?

A united front

As Bethel and Krasner both stressed this week, it’s too soon to determine exactly what happened that Friday night. The video, from Jennifer Tavern’s cameras, offers some information, but is not entirely clear; the officers did not have their body cameras turned on. The police department’s Internal Affairs Division and officer-involved shooting investigations unit are still investigating, as is the Citizen Police Oversight Commission; the DA’s office is awaiting the autopsy and other science and also conducting its own investigation.

What is tragically clear is that at the end of his encounter with Philadelphia police officers, Andrew Spencer was dead — and one of the officers had been shot in the leg. That story is not new, or especially uncommon. (In fact, another officer was shot, in the hand, the morning of Wednesday, January 31.)

That Krasner and his police department counterpart agree on transparency — or, really, most anything — is already a sign that we have entered a new era of public safety in Philadelphia.

Also not new: A debate over the police officers’ conduct leading up to the scuffle. Bethel insists they were conducting a routine security check of the store, while also looking for a suspect known to be carrying a gun. Meanwhile, a bystander— who said the cops “stopped and frisked” him for no reason — released a 30-second video of the episode on Instagram, with a caption that read, in part, that he “… had to shed light on the situation for his family and friends RIP Spence 🖤💪🏾 justice for all the young kings getting killed everyday.” According to the Inquirer, about 25,000 people viewed the video — which has since been removed — by Sunday morning. Many interpreted that video as presenting a different story than the one police had told the public.

The decision to release the five-minute-long footage from cameras a few days after the incident was an effort to give more context to the clip, quell potential uprisings and allow investigators more time to understand what happened. “The untruths that come from that are difficult to deal with, and so we’re working hard to disprove those rumors,” Bethel said.

Krasner made clear that he was watching the video for the first time, but their messaging was much the same.

“The reality is we may agree with interpretations of the Philadelphia Police Department completely,” Krasner asserted. “We may agree with them partially, or we may not agree with them. But today is not the day for that. Today is the day for transparency.”

A new day for cooperation?

That Krasner and his police department counterpart agree on that — or, really, most anything — is already a sign that we have entered a new era of public safety in Philadelphia. That may be a reflection of all that is new here since January: Mayor Parker, who ran on a promise of increased policing — including of “stop and frisk” — with an emphasis on community policing. Her much-lauded choice of Bethel for commissioner — a 30-year-veteran of the force, he was the right hand of former Commissioner Charles Ramsey, who led the department to the lowest gun violence rate in decades, and then left to reform the school-to-prison pipeline here and around the country. And a new Fraternal Order of Police president, Roosevelt Poplar, for the first time in 15 years.

Outlaw arrived in Philly in 2020 after a sexual harassment scandal led to former Commissioner Richard Ross’s resignation; she faced an uphill battle as an outsider, and as a woman — the first to lead the department — in the old boys’ network of Philadelphia police.

Six months in, she released a crime-fighting plan that was chock full of state-of-the-art reforms — most of which went unfunded and uninitiated. But her tenure was marked by pandemic cuts, the racial uprisings after the police murder of George Floyd, and a series of scandals and missteps. As a scathing 2022 audit by then-City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart showed, it was also a management disaster riddled with inefficient communications and training, outdated systems and poor use of personnel.

A few months before Dial killed Irizarry, the City agreed to pay $9.25 million to around 350 protesters on I-676 and in West Philly for police brutality during the 2020 demonstrations — an episode that Outlaw and Mayor Kenney first justified based (again) on a lie from officers on the ground. Both Outlaw and Kenney apologized for that; the mayor even took full responsibility, according to news reports. Three years later, Kenney barely acknowledged the police mishandling of Irizzarry’s death, and Outlaw had long lost the trust of citizens.

“We are a department that will be transparent, a department that will work to service our community, both our crime areas and throughout the city; we will continue to support our men and women in these regards.” — Kevin Bethel, PPD

It’s way too early to know if Bethel can achieve what has proven insurmountable to many chiefs before him: Making much-needed reforms to his department while also keeping the support and confidence of his officers. (Ramsey, for one, has complained that it is almost impossible to fire a bad police officer and have them stay fired, because of union rules.) Bethel walked a fine and serious line last week. He was visibly angry that an officer was shot, telling reporters outside Temple University Hospital that, “I’ve been here too many times. It is unacceptable.” He spent time at the press conference last week stressing the dangerous conditions under which his officers work — including in the area around Jennifer’s Tavern.

He was also cognizant of the people he (and his department) are supposed to serve — the citizens of Philadelphia. “We are a department that will be transparent,” he repeated, “a department that will work to service our community, both our crime areas and throughout the city; we will continue to support our men and women in these regards.”

Does this one press conference, one month into his tenure, indicate that the police has reformed itself? Of course not. There is still a young man dead. There are still questions about why the officers frisked the young men in Jennifer’s Tavern — though it indisputably turned up a gun — and why they ended up on the floor with Spencer. There is still — understandably — much distrust of how and who Philly cops are policing. Yes, we should be vigilant, and yes to asking all the questions of Bethel and his department. But a call for patience while Bethel and Krasner complete their investigation does not necessarily mean, as Ubiñas warned, that the department will return to its usual “stonewalling.”

Instead we might just be glimpsing something we have long needed in this city. Krasner and Bethel standing side by side could be a sign of our public safety officials actually working together, not against each other, to keep us safe — unlike what happened throughout much of the Kenney administration. Remember when City Council President Darrell Clarke took some of his colleagues to Chester, to learn how that city cut its murder rate — without inviting Kenney, Krasner or Outlaw? Or when Krasner and Outlaw traded barbs over how “fundamentally, there are very key disconnects there, as far as which crimes we prioritize,” as Outlaw put it? Or when Krasner and Kenney traded barbs over who should be charged in the South Street mass shooting?

All of those episodes left Philadelphians feeling not only less safe, but also like our well-being was in the hands of petulant children who cared more about power than about the citizens of their city — all while gun violence, until last year, steadily spiked and lawlessness took hold throughout. We deserved more than that then — and we deserve more than that now. That’s why Bethel and Krasner standing together at a podium, sharing the same message and exuding trust in each other, mattered. Maybe — could it be? — we are finally witnessing the change we need.