Sheyla Street grew up with voting in her blood — she is, after all, the daughter of State Sen. Sharif Street and granddaughter of former mayor John Street.

“I got dragged around a lot,” Street says. “Voting was something I didn’t think about — it’s like eating; you just do it.”

It never occurred to Street that voting might not be second nature to qualified adults, that it might take convincing to get people to the polls. In fact, Street thought volunteering to register her fellow Central High School students to vote a couple years ago was an easy way to fulfill the School District’s community service requirement.

MORE ON YOUTH AND LOCAL ELECTIONS

She learned differently pretty quickly—but that didn’t dissuade her. “I started to see the work as more valuable,” she says. “It’s about listening, about communicating. That’s what has led to youth in the past being ‘apathetic’ or not turning out as much—that no one was listening to them.”

Street was a sophomore when she started, still two years from being able to cast her own ballot. Now a senior, she’s captain of Central’s voter registration team, part of Philly Youth Vote, a citywide effort organized by Central social studies teacher Tom Quinn to get 18-year-olds ready to vote in the first election for which they qualify.

Measured success in getting out the youth vote

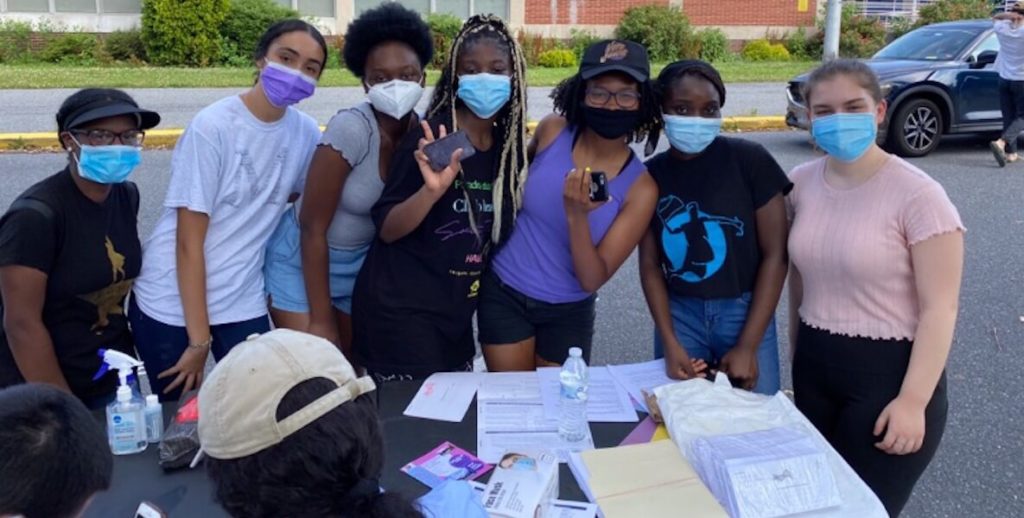

Last summer, Street and her team of 20 volunteers registered around 700 people to vote, not all 18-year-olds, but most of them first-time voters. Citywide, some 8,600 18-year-olds registered.

What’s more: They voted.

As was true generally, voting among registered 18-year-olds was up in 2020, with 74 percent casting a ballot, for a total of just over 6,500 people. That’s higher than the general voter turnout in Philly, which at 68 percent was the most in a generation, and up from 2016, when 69 percent of registered 18-year-olds voted. (This, too was higher than the general turnout of 64 percent.)

Part of that, of course, was Donald Trump. “You can’t discount that,” Quinn notes. But turnout among younger voters was also the result of a concerted effort on the part of many to get young people engaged in doing their civic duty: Quinn; students like Street; Lorene Cary’s #VoteThatJawn; and SEAMAAC, whose five-year-old youth voter outreach includes a phone and text banking app that has helped raise turnout 20 to 30 percent. That effort has worked to counter the tired narrative that youth are uninterested in politics — and, therefore, that politicians needn’t listen to them.

Growing their reach

Now, Philly Youth Votes is expanding statewide. Quinn is helping to change the social studies curriculum so it focuses more and earlier on voting. And students like Street are working to turn their registration efforts into a district-wide mandate to encourage voting among qualified students — to turn what they learn into action.

“We learn about everything under the sun, but somehow the things that are most important, most applicable to our lives, are pushed aside,” she says.

Quinn, one of The Citizen’s 2020 Integrity Icons, first started directing Philly Youth Votes after the 2016 presidential election when, as a member of the Caucus of Working Educators he was also encouraged to run for Committeeperson in his East Mt. Airy neighborhood. Starting in 2018, he led an effort to recruit teachers in the city’s 55 high schools who could get registration forms in the hands of the 12,000 seniors who would be old enough to vote that November.

“We met some people who had the opposite idea — don’t get involved,” Street says. “That’s a reflection of our system failing the people they’re supposed to serve. We’re trying to instill hope that we can reclaim this government for ourselves.”

Along with several local youth and community organizations, that effort has continued unabated, before and between every election. Last year, Quinn worked with Committee of Seventy to organize 27 candidate visits to virtual classrooms in 11 schools in the spring and the fall that allowed students to interview all the auditor general, and several state representative candidates. The interviews were recorded so they could be replayed by additional schools throughout election season.

Breaking the cycle

Research shows that “one of the main reasons young people don’t vote is because candidates don’t connect with them, and candidates don’t connect with them because they don’t vote. This was a way to break that cycle,” Quinn says. “When we first started this, and when we’re done with the pandemic, we need to get the candidates to walk into the schools themselves to see the conditions our students are dealing with.”

Here’s the other thing research has shown about voting: It’s a habit. And habits started young are the ones most likely to catch on. That means these engaged students participating in our electoral system are more likely to become engaged adults participating in the system—which is one way, maybe the only way, to ensure we have politicians consistently paying attention.

After the success of November, Quinn partnered with Angelique Hinton, who spent last year working for Michelle Obama’s When We All Vote, to form PA Youth Vote. (SEAMAAC is the group’s fiscal sponsor.) The intention, Hinton says, is to get every 18-year-old to the polls, yes; but also to bring together students from urban, rural and suburban schools around a common idea of citizenship.

So far, they have student participants from Philadelphia, Bucks County, West Chester and Harrisburg, and are working to recruit others from other suburbs and further west.

“Having these conversations helps all of us grow, and understand each other’s perspective — that’s a huge part of what’s missing today,” Hinton says. “Once people get to a point where they understand what they have in common as people, we can push elected officials to put people before politics.”

The work of PA Votes is intentionally nonpartisan, and intentionally local; the issues students care about, more often than not, are ones that are solved — or not solved — by their communities and by the state. Take school funding, for example: The concerns may be different in Philly and Bucks County, but decisions about how money is spent, and who gets it, affect all students in Pennsylvania.

“The federal government is so far removed from the issues these students care about,” Hinton says. “We want these students to realize that the people who really drive what’s happening in your community are your local officials, or even state officials.”

“We can reclaim this government for ourselves”

So far, the group is still in the early planning stages—they hold weekly Thursday planning meetings, recruit teachers to hold classroom sessions with candidates and brainstorm ways to spread throughout the state. They are also working on a podcast about the issues of teenagers in Pennsylvania as a way to be more engaged with their peers and spread the word about their work.

Closer to home, Quinn is also working with the district’s social studies curriculum office (run by another Integrity Icon, Shaquita Smith) to change how 12th grade classrooms district-wide teach civics, starting with moving the civics unit up to the first half of the year, rather than middle, before the November election. They are also adding in more action civics—ways to connect with candidates around issues and practical advocacy. “You can teach it in a way that tells them this is what voting is, and does — now go do it,” Quinn says.

Even that may not be enough, though. Led by Quinn, Street and other youth vote ambassadors are pushing the school district to join several others around the country in mandating that all high schools hold voter registration drives at least once a year.

According to the Center for Popular Democracy, schools in Arkansas and Iowa incorporate voter registration materials into their curriculum. In Maryland and Louisiana, there are dedicated voter registration assemblies. And in Virginia, where high schools statewide are required to distribute voter registration forms to qualified students, youth made up 20 percent of the electorate, the highest in the country (along with Georgia) in 2020. Compare that to Pennsylvania, where youth voters were just 13 percent of the total.

In February, after several students urged the School Board to adopt a voter registration program, Superintendent Bill Hite indicated he supported the plan.

“One of the things that the students have provided is a draft policy for how to look at voter registration as a part of what they experience as part of their day,” Hite said. “We are looking at that policy to ensure that that is something we can put into place, and hope to bring that as a recommendation for the board. So to the students, once again, thank you for not only talking about what a good practice would be, but submitting a draft policy as well.”

Meanwhile, Street and the Youth Votes team are back at it, registering the students who are newly qualified to vote this spring, and educating them about upcoming judicial and district attorney races. It’s an uphill battle, one that starts anew with every subsequent group of 18-year-olds. But, Street says, it’s worth the fight. It’s not just about voting, putting the right person in office, or turning out the wrong person. It’s about change.

“We met some people who had the opposite idea—don’t get involved,” Street says. “That’s a reflection of our system failing the people they’re supposed to serve. We’re trying to instill hope that we can reclaim this government for ourselves.”

Clarification: An earlier version of this story failed to mention the role of SEAMAAC in registering and getting youth out to vote in Philly. The organization is also Pa Youth Votes’ fiscal sponsor.