Can I get a change? (yes u can)

So began our 5th annual Ideas We Should Steal Festival® presented by Comcast NBCUniversal, with a rap created and performed by Hill-Freedman World Academy students DaShawn Hudson and Jaden Alvin, from their new album Growing Up Black (available on SoundCloud).

And a more fitting start there could not have been. We heard about change from all corners: from Black Thought of The Roots, for whom finding his voice meant changing his (and our) world; from the architects of Chester’s gun violence reduction; freedom warriors Andrew Yang, Jennifer Rubin and Michael Steele; criminal justice pioneers Marc Howard of the Frederick Douglass Project and Father Greg Boyle of Homeboy Industries; and even from restaurateur Will Guidara.

There were many lessons learned throughout the day, but one theme stood out above all others: expansion — of our capacity and willingness to connect to others; of democracy; of justice for all; of proven solutions; of hope.

This year’s event, at the Comcast Technology Center, was sponsored by Independence Blue Cross, United Way of Greater Philadelphia and Southern New Jersey, Fanatics, FS Investments, DARCO Capital and more thought leaders, change makers, good citizens and community partners.

The full playlist of the day is available on our YouTube channel, here. For a written snapshot — and some actual snapshots — of the event, scroll down to see what we learned.

It is possible to cut gun violence.

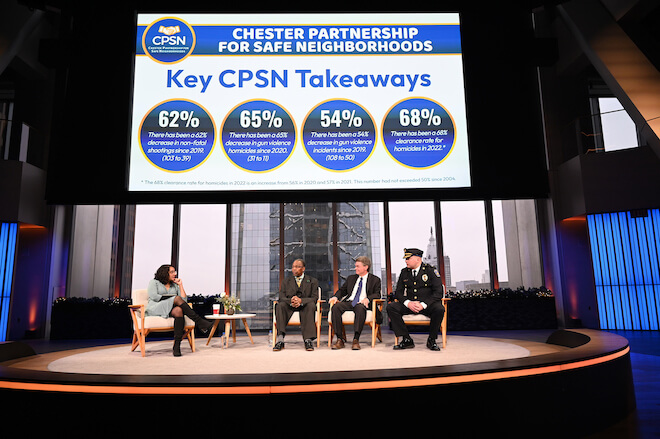

Over the last two years, Chester, the long beleaguered, impoverished city in Delaware County, has reduced gun violence by 60 percent — while up I-95 shootings have continued to rise in Philadelphia. The key: Collaboration.

The city of 32,500’s police department, led by Commissioner Steven Gretsky, and the Delaware County district attorney’s office, helmed by Jack Stollsteimer, launched Chester Partnership for Safe Neighborhoods, along with Mayor Thaddeus Kirkland and several other agencies, to enact a version of focussed deterrence. As the men explained to The Citizen’s Roxanne Patel Shepelavy, they created a neighborhood engagement plan; fostered relationships between community members and officers through community policing; and offered a mix of help to those who are at risk and consequences for those who commit acts of violence.

The message, according to Kirkland: “It’s not lock them up. It’s help them up.”

Art is like oxygen.

The Roots frontman Tariq “Black Thought” Trotter met Jane Golden, executive director of Mural Arts Philadelphia (MAP), when he was 12 years old, after being arrested for tagging buildings in South Philly. Even at that young age, Trotter had already experienced extreme trauma — the murder of his father, the burning down of his house, his brother’s arrest. “I’m no anomaly,” he said. “It’s pretty common for young people in Philadelphia to experience a comparable level of tragedy and trauma. We all need an outlet.”

Trotter became part of Golden’s Anti-Graffiti Network, which subsequently became MAP.

“Philadelphia is the City of Brotherly Love, but it’s also the city of the arts,” Trotter said, in a panel moderated by the Citizen’s Larry Platt. “That’s a great deal attributable to Jane and her efforts here. These murals are our armor.”

By that time, Golden had moved back east from a stint in California to see how she could “put art to work for the greater good” — and when she realized that making art could transform the lives of kids, adults, and entire communities.

“Art is like oxygen,” Golden said. “It should be nonnegotiable. It should be everywhere.”

Art is also essential to how we relate to each other.

As commissioner of Chicago’s Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events, Erin Harkey has had to climb a seriously uphill post-pandemic battle. In Chicago, as worldwide, the arts and culture sector was among the most negatively impacted by Covid. Harkey’s city’s arts scene is still in a recovery phase.

Her solution: “Deepen public sector investment.” Today, every one of Chicago’s city departments has a role to play in the arts — including the planning department, which has hired artists to run community engagement for the City’s first comprehensive plan since the 1960s. Under Harkey, the City has established Esteemed Artist Awards, making grants to support diverse local artists’ current projects, and has brought meaningful new art into every one of Chicago’s 77 neighborhoods, especially on the city’s impoverished West and South sides.

“Arts is something we need to plan for, like we plan for public safety, like we plan for roads and bridges,” said Harkey. “The arts are absolutely essential to our quality of life and how we relate to each other.”

We need to change the way we look at incarcerated people.

Georgetown University’s Marc Howard, director of the Frederick Douglass Project, has helped to exonerate four innocent people in prison — including his best friend from high school — and is doing work that helps outsiders “realize and recognize the humanity of incarcerated people and giving them the support they need to succeed.”

This means bringing cameras and reporters into prisons, bringing formerly incarcerated people onto campus for classes, and encouraging law students to work on criminal cases. Changing the narrative about who is in prison, and why they are there, is the mission of the Law & Justice Journalism Project, for which both veteran journalists Cherri Gregg and Emily Bazelon are advisors. LJJP helps reporters enter the field, and subsidizes them so they can afford to stay there, doing good work.

“Black and Brown people are 12 times more likely to be wrongfully convicted,” said Gregg, a former attorney, who blames, at least in part, “the images that society sees of us.” Responsible reporting, she believes, includes covering both the negative and the positive, the problems and the solutions, alongside the communities.

“We have to talk about root causes,” she said, adding that we also have to train reporters from communities to do the reporting.

Housing reparations is one way to to compensate Black residents for past discrimination.

The Chicago suburb of Evanston, IL — led by Mayor Daniel Biss — became the first city in the U.S. to enact housing reparations. Last year, Evanston’s Restorative Housing Program distributed $25,000 housing grants to longtime Black residents and descendants of Black residents who were impacted by housing discrimination. The sale of recreational cannabis funds the program.

As Biss told former Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter, housing reparations is just one of the ideas Evanston is trying to lift up those in poverty; this year, the city also launched a Universal Basic Income pilot, distributing cash every month to several families in need. Meanwhile, Evanston has started to share data about its reparations program with other cities, including some large ones, across the country.

“Each community has a different history and feels a responsibility to repair different harms that, in most cases, they’ve created,” Biss said.

A path to tech success should be there for everyone.

Michael Ellison believes in coding. He believes in diversity. He has his own life — growing up, at times, homeless, with one parent in prison — and his career — creating ClassMetric, a customer data hub that later became Segment, then selling it to Twilio for $3.2 billion — to prove it. Today, the founder of CodePath works to give underrepresented students access to training and careers in tech and engineering.

He recalled his first venture: “I started my first nonprofit when I was 19. We didn’t have any connections. We literally Googled, How to raise money. On Google. We heard that Goldman Sachs had a lot of money, so we started dialing phone numbers for Goldman Sachs.” Somehow, Ellison ended up with tickets to a conference, where he ended up pitching the … chairman of the board of Goldman Sachs.

CodePath partners with more than 70 two- and four-year colleges around the country to create coding curricula for up to 10,000 students, helps them get internships and jobs, and redesigns early recruitment programs for large tech companies, including Salesforce, to help them build the most qualified and diverse workforce.

Now in Miami, Codepath is partnering with that city to build a tech pipeline for low-income residents with support from Comcast and the Knight Foundation, through programs at Miami Dade Community College and Florida International University.

“Thousands of students from similar backgrounds don’t have the opportunity to reach their full potential,” Ellison told NBC10’s Claudia Vargas. “Codepath is very focused on driving diversity in the nation’s most competitive technical roles, but doing that in a way that changes systems.”

Hospitality that makes people feel connected can save a city.

There are many behind the scenes secrets to running a restaurant. But Will Guidara, who took the helm of New York City’s Eleven Madison Park at age 26, and turned it into the top restaurant in the world — says one of the biggest secrets is this:

Success “has less to do with what you’re serving and how you serve it, but how you make people feel.” To that end, Guidara told Wharton’s Ken Shropshire, that he ran his restaurant with the 95-5 rule: 95 percent of his budget was kept tight, and 5 percent was open for staff to use as they chose to serve customers. In one case, that meant running out to buy a sled and book a carriage to Central Park so young visitors from Spain could enjoy their first snowfall.

This is what Guidara has dubbed “Unreasonable Hospitality,” which is also the title of his bestselling book. And it’s the message he had for the city, as well: Doing more when others do less, connecting with customers and constituents, is the way to make everyone feel they are being served.

We need more goodness — not just “morality” — in the world.

There is a difference, Father Greg Boyle of Homeboy Industries and Rev. Bill Golderer of United Way of Southeastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey, will tell you, between morality and goodness. Said Boyle: “The moral quest has never kept us moral. It’s always kept us from each other … Mother Theresa said, ‘If we have no peace, it is because we have forgotten that we belong to each other.’ The goal is to create a community of beloved belonging.”

Boyle and Golderer have both sought out this community, this kinship among people who are most overlooked. In Boyle’s case, that’s members of gangs in and around Los Angeles, through HomeBoy Industries. In Golderer’s, it’s people experiencing housing and food insecurity here in Philadelphia, through Broad Street Ministry.

“Social change in Philadelphia is the ultimate contact sport,” Golderer said to Boyle and Rev. Chaz Lattimore Howard, Penn’s chaplain. “Every person I’ve ever met is in need of healing. And that starts with me … I experience personal healing by being in front of people who could not hide the healing they’re in need of … What we don’t need is a savior. We need a healer. When you listen to those who have mayoral aspirations, listen closely for the healing they could bring. This community, the City of Brotherly Love and Sisterly Affection, requires healing.”

Democracy is not a spectator sport.

The final panelists to the stage represented a wide range of smart American viewpoints. Jennifer Rubin, of The Washington Post, long considered herself a conservative — in the traditional sense of the word — but shuns party identity, especially in the post-Trump era. Michael Steele chaired the Republican National Committee — also pre-Trump. Ali Velshi hosts a show on progressive-leaning MSNBC, and Andrew Yang, former candidate for U.S. president and for mayor of New York, has founded his own party, Forward.

What’s wrong with U.S. politics today? Why is our country so polarized, and our fractured leaders so unable to get things done? As Yang said: “We have a political system that rewards problems getting worse and festering, as long as I can get you upset about it.”

Yang’s solution: Revamping how we vote through open primaries, which allow citizens to vote for candidates from any party in the primary; and ranked-choice voting, which lets voters select candidates in order of their preference and ensures only the one with at least 50 percent of the vote wins. To see how that works, we can look to Alaska’s most recent election.

Yang and Steele also noted that we, as citizens, must do our part: Americans give Congress a 28 percent approval rating — but re-elect 94 percent of its members. “Our job is to hold the rat bastards in office accountable for what we’re doing,” said Steele.

“The most powerful words in all of our documents written about this country, in my view, are these: We, the people,” Steele went on. “Our government was not established for an institution by an institution. It was not established for a political party. Our founders were reticent about factions being formed. As short-sighted as they were, as flawed as they were, they placed that power in those three words.”

Rubin, too, called on all of us to take the reins of the American freedoms we hold dear: “Democracy is not a spectator sport. Unless you participate, it’s going to fail. Run for office. Join a campaign. Don’t just give money. Don’t just write a check. Subscribe to a newspaper. Do something. Become a political participant.”