This November marks the 50th anniversary of the murder of a lesser-known Black hero, arguably the most innovative educator of his time: Marcus Foster.

Known for turning around some of Philadelphia’s and Oakland’s most troubled schools, Foster was ahead of his time. He gained prominence in the 1960s and 70s for setting a high-water mark that public education struggles to achieve today. His value proposition and overarching educational philosophy are as relevant now as they were five decades ago.

I attended the same elementary school where his wife, Albertine “Abbe,” taught. As a young boy, I used to see Foster all the time at school events. Back then, I didn’t grasp how important he was.

From 1966 to 1969, Foster was the principal at my neighborhood high school, Simon Gratz High. Before he took over, Gratz was academically underachieving and notoriously violent. “Gratz is for rats” was the saying then.

But Foster was a visionary. He could see the hidden potential within a school that exceeded its dismal conditions.

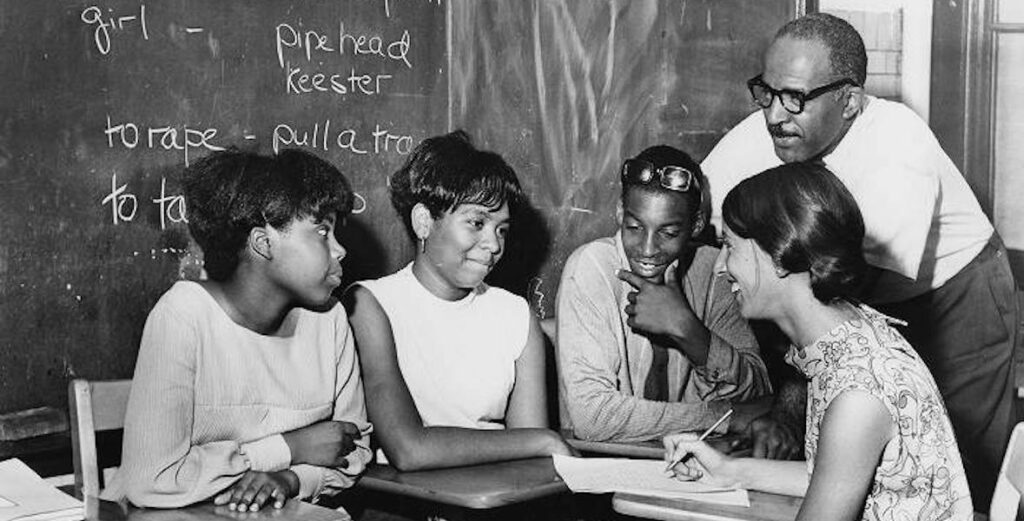

Marcus Foster, visionary

Foster emphasized academic rigor. He brought back Latin and other college preparatory courses, shining a pathway toward higher education for many young Black men and women.

Foster knew that a college education provided a roadmap to the economic prosperity for the young Black men and women of Gratz. He once famously told Gratz students, “You don’t have to have middle-class values, but you do have to have middle-class skills.”

He didn’t see students for their deficits. Instead, Foster set higher standards for them. Furthermore, he challenged everybody in his school — teachers, administrators and students alike — to practice personal responsibility.

Foster rarely accepted excuses for failure, challenging educators and decision-makers to drop their victimhood mentality. In his 1971 book, Making Schools Work, Foster wrote, “Inner city folks … want people in there who get the job done, who get youngsters learning no matter what it takes. They won’t be interested in beautiful theories that explain why the task is impossible.”

For Foster, educational success happened in both the classroom and the home, so parental involvement was critical to the success of his students. In his 2012 biography about Foster, In the Crossfire, John P. Spencer wrote how Foster “portrayed parents as an ally to be mobilized,” not “an obstacle to overcome.” Foster created “storefront schools” and vocational programs with neighboring businesses that helped parents just as much as they helped students.

Because of his efforts, Foster gave Gratz the academic credibility it never had. Under Foster’s watch, Gratz’s college acceptance rate doubled while also slicing its dropout rate in half. These numbers flipped after he left Gratz in 1969 — a further testament to his impact.

Foster’s success is due in part to how he embraced educational competition.

Bill Parcells, the renowned NFL coach, once famously said, “If they want you to cook the dinner, at least they ought to let you shop for some of the groceries.”

That’s what Foster did: By increasing academic standards and achievement, Gratz became an attractive educational destination for students and families, giving Foster the cream of the crop of students — both within and outside Gratz’s catchment area.

By making his school competitive, Foster created a cycle of success at Gratz: A new and improved school resulted in a new-and-improved student body, which made the school even better with each passing year.

Sadly, militants from the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) gunned down Foster in 1973. SLA thought assassinating Foster would inspire protests. But all they did was commit, as one SLA member later admitted, “a public relations mistake.”

Much to SLA’s surprise, Foster was highly respected and loved within every community he touched — from Philadelphia, where several sites memorialize his legacy, to Oakland, California, where he now rests eternally.

We can still feel Foster’s impact today. Gratz alumni from Foster’s era include judges, business owners, educators, and community leaders.

If alive today, Foster might advocate for school choice. He actively lobbied parents to choose his school over other options outside the neighborhood. And though he did his best to make Gratz a better alternative, Foster also respected the right to choose.

Through academic rigor, sensible discipline and a competitive spirit, public schools could replicate Foster’s vision for kids.

David Hardy is Interim President of Girard College and a Distinguished Fellow at the Commonwealth Foundation.

The Citizen welcomes guest commentary from community members who represent that it is their own work and their own opinion based on true facts that they know firsthand.

MORE OPINION IN THE PHILADELPHIA CITIZEN