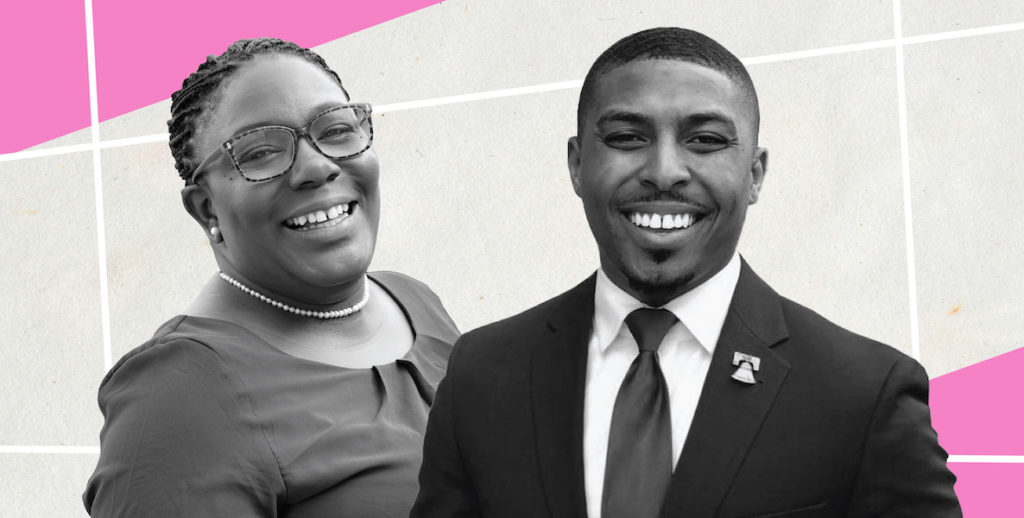

Last week, I caught up with the two progressive Working Families Party candidates for City Council who have many in the political establishment all shook up. Kendra Brooks, of course, is an at-large incumbent, having won her seat in 2019. Pastor Nicolas O’Rourke came up just short back then, but has a good shot this time around. Both are vying to win the two City Council seats reserved in the Home Rule Charter for the city’s minority party.

Until Brooks, that meant the Republican party. Now there is much handwringing over the prospect of an all-Democratic Council with two at-large seats held by progressive Working Families Party candidates. (Forty-four-year Republican incumbent Brian O’Neill in the Northeast’s 10th District is being challenged by Gary Masino of the Sheet Metals union, who has the support of Ryan Boyer’s Building Trades.)

Bob Brady, Philly’s Democratic party chair, is pissed, threatening his 3,000 foot soldiers with expulsion if they support Brooks and O’Rourke who, by definition, will be pulling votes from his candidates. The newly awakened Republicans, on the other hand, argue that the Working Families party — with all of a reported 14 registered voters — is not really independent of the Democrats, that it’s really a wing of the Democratic party, the Tea Party of the Left.

Yes, to the non-politico, this all might qualify as inside baseball. But I reached out to both Brooks and O’Rourke with a slightly different set of concerns that are more practical in nature. I’m having a tough time wrapping my head around the political rationale for their campaigns. Both are bright and energetic, with compelling personal stories. And both very much want a more just, equitable and thriving Philadelphia.

But how we get there is often the rub. Ours, after all, is a city government desperately in need of reform — unless you’re okay with a 63 percent increase in spending (from $3.8 billion to $6.2) and a 108 percent jump in the murder rate (248 to 516) over a mere eight years, not to mention a loss of jobs and population and a litany of elected official indictments during the same time period. You okay with that return on your taxpayer investment?

All politics is not national

I wanted to ask Brooks and O’Rourke whether, in a city where registered Democrats outnumber Republicans by nearly 8 to 1, essentially laying blame for what ails us on the absent Republican Party is really a platform for change — or is it just a smart way to acquire power?

To be clear: I am second to none when it comes to pointing out the odiousness of today’s national Republican Party; in fact, calling it a party is too generous. It’s a cult, with a few cowards remaining in it who, despite knowing better, are loath to stand up to Dear Leader.

“I reject the bifurcation of the local Republican party from the national Republican party. The party of Donald J. Trump doesn’t deserve to be in power.” — Nicolas O’Rourke

But it’s a different story locally. Here, the Republican Party long ago made a deal to accept the crumbs of patronage in return for not competing in elections, and thereby not governing. So isn’t it a political sleight of hand at best to blame them for our intractable poverty or widespread violence?

“I reject the bifurcation of the local Republican Party from the national Republican Party,” O’Rourke told me. “The party of Donald J. Trump doesn’t deserve to be in power.”

When we spoke, Brooks concurred that, essentially, Trump is on the ballot in our local Council general election. “I see where you’re going,” she said. “The Republican party is the party of Trump and we’ve seen what they’ve done. It’s not a serious governing party and it attacks voting rights and abortion rights. So for me, stopping that narrative across the board is the most important thing.”

So noted. But the beauty of local politics is that, when functioning well, it’s devoid of ideology. You either pick up the trash or you don’t. As former Mayor Michael Nutter says, “There’s no liberal or conservative way to fill a pothole. You just fix the fucking pothole.”

Republican David Oh, now an unprepared candidate for mayor, spent 11 years on Council. Did he attack voting rights? Did he threaten a woman’s right to choose? Actually, because of his minority party status, he kind of did nothing, legislatively speaking.

“That’s the problem!” Brooks smartly countered.

Touché. Why, after all, am I arguing for perpetuating do-nothingness? Because Philadelphia is not an island unto itself, as Brooks seems to suggest.

“In Harrisburg, the state legislature has its own work to do,” Brooks said. “In Philadelphia, unless we’re preempted by the state, the Working Families Party agenda is completely separate.”

O’Rourke seems to agree. While conceding that there will be a steep learning curve were he to win next month, he’s prioritizing “connecting with constituencies that have been left out so their voices are advocated for, and getting to know staff in Council and the Municipal Services Building so that I can hit the ground running.”

What’s the reform?

There’s nothing wrong with that, of course, except that the WFP approach appears to be a type of political isolationism. Fact is, we live in a Commonwealth that is often controlled by Republicans. For every dollar Philly pays in taxes, it gets back nearly $3 from the state. Don’t you think it may be harder to get the most out of our Republican-controlled Senate if you’ve eradicated Republicans from local governance, and demonized them to boot?

Another Democratic Socialist, State Senator Nikil Saval, has demonstrated just how important it is for progressives to find common ground with Republicans. Saval has shown a practicality that politicians at all levels would do well to emulate. O’Rourke admirably says that, if elected, he’ll be emphasizing serving “people with their backs to the wall,” which is consistent with the WFP platform. But have they given a lot of thought as to how you remove that wall, which is to say pursue an opportunity agenda?

Wouldn’t a program that provides a pathway to the middle class, as Washington, D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser has embarked upon, truly help working families? Instead, Brooks and O’Rourke are classic redistributionists in a city where 17 of the top 20 employers pay no taxes. There’s precious little to redistribute, in other words.

“In Harrisburg, the state legislature has its own work to do. In Philadelphia, unless we’re preempted by the state, the Working Families Party agenda is completely separate.” — Kendra Brooks

Brooks’ wealth tax proposal makes for an instructive case in point. Taxing unrealized gains in stocks and bonds plays to the Berniecrats, but what problem is it solving for here? After all, Philadelphia suffers from no dearth of spending; the City’s budget is at an all-time high. Moreover, as Jennifer Pahlka, Obama administration alum and author of Recoding America: Why Government Is Failing in the Digital Age and How We Can Do Better, points out on the latest episode of our How To Really Run a City podcast, being able to implement policy tends to be more important than the policy itself.

So, given that the IRS doesn’t track unrealized gains from stocks and bonds, does Brooks have a plan for how to administer this new, complicated tax? Are we going to have to trust the likes of Rob Dubow, the city Finance Director who misplaced millions of taxpayer dollars and didn’t even reconcile the city’s bank accounts for seven years, to figure out who owes what?

“We would have to figure out the structure for that,” Brooks told me, which kind of puts the cart blocks ahead of the horse. “But I didn’t make this completely up from nowhere. We had a wealth tax in place until 1996 and then dismantled it.”

Well, actually, Pennsylvania had a Personal Property Tax of holdings such as stocks, bonds, and mutual funds, but the state Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional in 1997. Then-Mayor Ed Rendell tried to come up with a local wealth tax in its place, but it proved too difficult to implement and was found to drive jobs from the city limits.

The point is that we hear precious little from our progressive candidates about enacting reforms that can make your government work better for you. Hardly anything about ridding the city of councilmanic prerogative, or adopting ranked-choice voting, or enacting term limits. In fact, when asked for innovative programs the city ought to embrace, O’Rourke talked haltingly about a program in Columbus, Ohio his father had told him about that hires returning citizens to help beautify the city. When I asked if he supports term limits, he started to think about it aloud, saying he “might, but I wouldn’t want to write anything in stone.”

After talking to both O’Rourke and Brooks, it becomes clear that, to them, reform begins and ends with the Working Families Party itself.

Contrast that to Portland, Oregon, where progressivism run amok has given way to real political reform. Earlier this year, voters backed a ballot measure that rethinks the very essence of local governance. It strengthens the power of the mayor, adopts ranked-choice voting, more than doubles the number of City Council members, and creates a series of citizen-led commissions to implement these vast changes. My favorite: A five-person salary commission will determine how much the mayor, the city auditor and all council members should be paid annually. How’s that for an idea to steal? Your elected officials actually working for you.

Look, O’Rourke and Brooks have a lot to offer. O’Rourke is charismatic and likable, with an uplifting preacher’s patois, which can be priceless in politics. And Brooks showed some political chops in endorsing then-gubernatorial candidate Josh Shapiro early last year — when he was looking to shore up his progressive bona fides. (Which Shapiro repaid with a recent endorsement, much to Brady’s chagrin.).

“We built a relationship over a year-and-a-half by having hard conversations, primarily around criminal justice reform,” Brooks said of her relationship with the Governor.

But like many of those on the extremes of the political spectrum, both O’Rourke and Brooks tend to be sure of the answer regardless of the question. They are the political embodiment of what the evolutionary psychologist Leda Cosmides has called instinct blindness: “Intuition systematically blinds us to the full universe of problems our minds spontaneously solve.”

That really is the question raised by the rise of the Working Families Party in Philadelphia, isn’t it? Do we need more certainty on old tactics, no matter what the evidence might say? (See: Rates, gun violence, poverty and job growth). Or can we get to the same end — a more just, equitable and thriving city — by thinking anew about the unsexy blocking and tackling that actually delivers real change in shared urban life?