Earlier this year, Citizen Co-founder Larry Platt asked me to serve on a committee to honor Judge A. Leon Higginbotham, whose contributions to the struggle for racial justice have not been properly memorialized in any way in the City of Philadelphia. To rectify this oversight, The Philadelphia Citizen, Mural Arts Philadelphia, and the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School have raised funds to commission a mural to celebrate his legacy.

In 2018, I wrote an article and prepared a comprehensive chronology on the history of the Black Philadelphia lawyer for a continuing legal education program called “Standing on the Shoulders: The Black Philadelphia Lawyer” that my firm, the Tucker Law Group, organized. Platt asked if I would revise those materials as a companion integrated chronology for the mural that examines Higginbotham’s life and work in historical perspective. I am honored to serve on the committee and to provide this research.

Judge A. Leon Higginbotham’s brilliant career as a lawyer, jurist and scholar began in 1952 when he graduated from Yale Law School and moved to Philadelphia. Over a period of 46 years, his contributions to the struggle for racial justice and human dignity exemplified the superb legal advocacy of many of the courageous Black Philadelphia lawyers who came before him and on whose shoulders he stood.

Higginbotham’s predecessors and contemporaries exemplified the superior legal acumen of the storied “Philadelphia Lawyer.” That term originated when Philadelphia lawyer Andrew Hamilton successfully defended publisher John Peter Zenger in his 1735 libel trial in New York that established the concept of press freedom in the United States. After the verdict, spectators said “Only a Philadelphia lawyer could have done it.” The term first appeared in print in 1788 in the Universal Asylum and Columbian Magazine published in Philadelphia.

Judge Higginbotham’s contributions (find them in the timeline below marked with a “⚡️”) and those of other black Philadelphia lawyers transcended Philadelphia and the legal profession and benefited generations in America and around the world regardless of race, gender, religion, or social status. Judge Higginbotham and these other Black lawyers are authentic American heroes.

- Part I: Early Black Lawyers in America and Philadelphia (1845-1952)

- Part II: Higginbotham and His Contemporaries (1952-1962)

- Part III: Higginbotham’s Jurisprudence, Scholarship and Public Service (1962-1998)

Part I: Early Black Lawyers in America and Philadelphia (1845-1952)

1845

-

- George Boyer Vashon, the first Black graduate of Oberlin College, decides to become a lawyer in Pennsylvania. After studying law in the offices of a prominent Pennsylvania lawyer, in 1847, he applies for admission to the bar of Allegheny County. His application is rejected on the grounds that state law limited bar admission to White men. Vashon leaves Pennsylvania to become the first Black admitted to the New York State Bar in 1848, and then reapplies for admission in Allegheny County in 1867 after the Civil War. A Common Pleas Court panel again denies his application. Vashon would go on to become the third Black lawyer admitted to practice before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1868 and, in 1869, the first admitted to practice in the District of Columbia. He was posthumously admitted to the Allegheny County Bar in 2010.

1850

-

- University of Pennsylvania officially establishes a law school.

1854

-

- Lincoln University is founded as Ashmun Institute. Graduates include: Harry W. Bass (1886), the first Black Pennsylvania legislator; Herbert E. Millen (1910) the first Black judge in Pennsylvania; Robert N.C. Nix, Sr. (1928), the first Black elected to Congress from Pennsylvania; and Thurgood Marshall (1930), the first Black U.S. Supreme Court justice.

1857

-

- Dred Scott v. Sandford holds that slaves were not citizens or “persons” under the Constitution and had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” Triggers the Civil War.

1861-1865

-

- Civil War.

1865

-

- The 13th Amendment is ratified, abolishing slavery and repudiating Dred Scott case.

- Abraham Lincoln is assassinated. Andrew Johnson becomes president. Under Johnson’s administration, several Southern state legislatures pass restrictive “Black Codes” to control the political and social activities of the newly freed slaves and undermine Reconstruction.

- Jonathan Jasper Wright, a Pennsylvania native and graduate of Lancasterian University in Ithaca, New York, becomes the first Black lawyer admitted to practice law in the state, in Luzerne County. However, Wright moves to South Carolina and, two years later, is elected to the South Carolina Supreme Court, becoming the country’s first Black lawyer elected to an appellate court .

- Ku Klux Klan is founded in Tennessee by a group of former Confederate soldiers.

- John S. Rock, who was trained as a doctor and a lawyer, is the first Black to be admitted to practice before the U.S. Supreme Court.

1866

-

- Civil Rights Act passes, explicitly repudiating Dred Scott.

- Jonathan Jasper Wright (1840-1885) first Black admitted to Pennsylvania Bar.

1868

-

- The 14th Amendment is ratified, giving newly free slaves the right to due process and equal protection of the laws, and protecting them from state action.

- George Lewis Ruffin is the first Black in America to receive a law degree when he graduates from Harvard Law School.

1869

-

- John Mercer Langston (1829-1897) founds and becomes the first dean of Howard University Law School. Between 1871 and 1944, Howard graduates more than 1,000 Black lawyers.

1870

-

- The 15th Amendment is ratified, giving Black men the right to vote.

1872

-

- Charlotte E. Ray (1850-1911), an 1872 Howard Law School graduate, is admitted to the Washington, D.C. bar, becoming the first Black woman lawyer in the U.S. She is also the first woman of any color granted permission to argue before the U.S. Supreme Court.

1875

-

- Civil Rights Act bans discrimination in public accommodations.

1876

-

- John Daniel Lewis and Jeremiah H. Scott are the first Black lawyers admitted to practice in Philadelphia and, in 1877, become the first Blacks admitted to the PA Supreme Court. Until 1891, John Daniel Lewis is the only practicing Black lawyer in Philadelphia and is a forceful advocate for civil rights in the city. In 1880, he is the first Black to prosecute a criminal case in the name of the Commonwealth.

1878

-

- American Bar Association is founded.

1880

-

- Strauder v. West Virginia decides that excluding Blacks from jury service is a denial of Equal Protection.

1881

-

- Thomas T. Henry, who studied law in John Daniel Lewis’ law office, is the first Black lawyer to pass the bar examination administered in Philadelphia County.

1883

-

- U.S. Supreme Court concludes the 1875 Civil Rights Act is unconstitutional. Frederick Douglass and most Blacks consider this to be the most devastating blow to civil rights since Dred Scott. This results in widespread discrimination in a congeries of private settings and the proliferation of Jim Crow laws in states throughout the South.

1887

-

- Pennsylvania passes the first Equal Rights Law.

1888

-

- Aaron A. Mossell, Jr. (1863-1951) is the first Black to graduate from Penn Law School. While in law school he writes a paper arguing that state laws that prohibit interracial marriage violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution. The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Loving v. Virginia (1967) reaches the same conclusion.

1891

-

- John Adams Sparks and Thomas Wheeler are the first Black lawyers to argue a case before the PA Supreme Court.

1893

-

- William H. Ridley (1827-1945) is the first Black admitted to the Delaware County Bar Association and remains the only Black member until his death in 1945.

- George Jackson is the first Black admitted to the New Jersey bar.

1895

-

- Temple University Law School opens as the Philadelphia Law School of Temple College.

1896

-

- Plessy v. Ferguson holds that “separate but equal” facilities in public accommodations do not violate the U.S. Constitution.

1899

-

- George Henry White, a teacher, lawyer, banker and member of Congress, purchases 1700 acres of land in Cape May County, New Jersey and establishes a Black town that he names Whitesboro. By 1906, the town had a population of 800. White moves to Philadelphia in 1905 where he has a successful law practice and opens the People’s Savings Bank. Originally from North Carolina, White serves in Congress from 1897 to 1901 as the only Black in the House of Representatives.

- W.E.B. Dubois publishes The Philadelphia Negro, which identifies 10 Black lawyers practicing in Philadelphia: Theodore Minton, Aaron Mossell, John Sparks, George Mitchell, A. F. Murray, Thomas Wheeler, George Edward Dickerson, John C. Asbury, William Fuller and Henry W. Bass.

1902

-

- George Edward Dickerson is the first Black graduate of Temple law school in the school’s second graduating class of 11 graduates total.

- Pennsylvania State Board of Law Examiners, appointed by the PA Supreme Court, sets uniform statewide standards for admission to the bar. Prior to this there were 54 different examining jurisdictions in each county with different standards including testing and fitness requirements. Becomes effective in 1903.

1909

-

- NAACP is founded.

“What Thurgood Marshall and Charles Hamilton Houston were to the first half of this century, Judge Higginbotham was to the second half,” says Jesse Jackson.

1915

-

- The Great Migration begins. Before World War I, 90 percent of Blacks lived in the South. Between 1915 and 1960, about five million Southern Blacks move to the North and West. During the initial wave, the majority of migrants move to major Northern cities such as Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia and New York. After World War II, the migration continues with thousands of Blacks moving out west. This influx of Blacks into these major cities allows Black lawyers to expand their practices from primarily criminal work to civil litigation, business law, personal injury, real estate and estate planning.

1917

-

- NAACP organizes a silent march in Washington, D.C. in response to lynchings, race riots and social injustice. Considered the first major civil rights demonstration of the 20th century, almost 10,000 Blacks participate.

- J. Austin Norris (1890-1976) graduates from Yale Law School.

1919

-

- During the “Red Summer,” as it is called by James Weldon Johnson, race riots occur in July and August in more than three dozen cities. The riots, initiated by White mobs against Blacks, result in the deaths of several hundred Blocks around the country.

- 83 Blacks are lynched. Many are soldiers returning home from World War I.

- The 19th Amendment is ratified, giving women the right to vote.

1908–1920

-

- No Black lawyers are admitted to the Pennsylvania Bar.

1920-21

-

- First three Black lawyers are admitted to the American Bar Association: William Henry Lewis, Butler Roland and William R. Morris. Several Southern bar associations object, claiming that they had failed to disclose their race and should not be admitted. The national leadership relents and agrees that the Southern associations had the power to veto the membership of any future Black members. Also, Black applicants are required to list their race when applying for membership. No new Black lawyers are admitted until 1943, when the policy is rescinded.

1922

-

- Charles Hamilton Houston (1895-1950) graduates from Harvard Law School, where he has been the first Black editor of the Harvard Law Review. He is also the first Black to receive a Doctor of Juridical Science degree (SJD) from Harvard. After practicing with his father, he becomes Vice Dean of Howard Law School. In 1932, he becomes full-time counsel for the NAACP, where he is the primary architect of the litigation strategy that resulted in Brown v. Board of Education and numerous other precedents that granted equality of access to Blacks. Philadelphia’s Juanita Kidd Stout works as his secretary in 1942.

- Over 3,200 Blacks are lynched between 1889 and 1922.

1923

-

- Raymond Pace Alexander (1897-1974) graduates from Harvard Law School, is admitted to the Pennsylvania Bar, and starts his own law firm because no White firms would hire him.

1924

-

- Future Congressman Robert N.C. Nix, Sr. (1898-1987) graduates from Penn law school.

- Raymond Pace Alexander successfully enjoins the Chestnut Street Theatre from excluding Blacks from a production of the Ten Commandments. He later wins large verdicts against the Pennsylvania and Reading Railroads and the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company (later SEPTA) for racial discrimination.

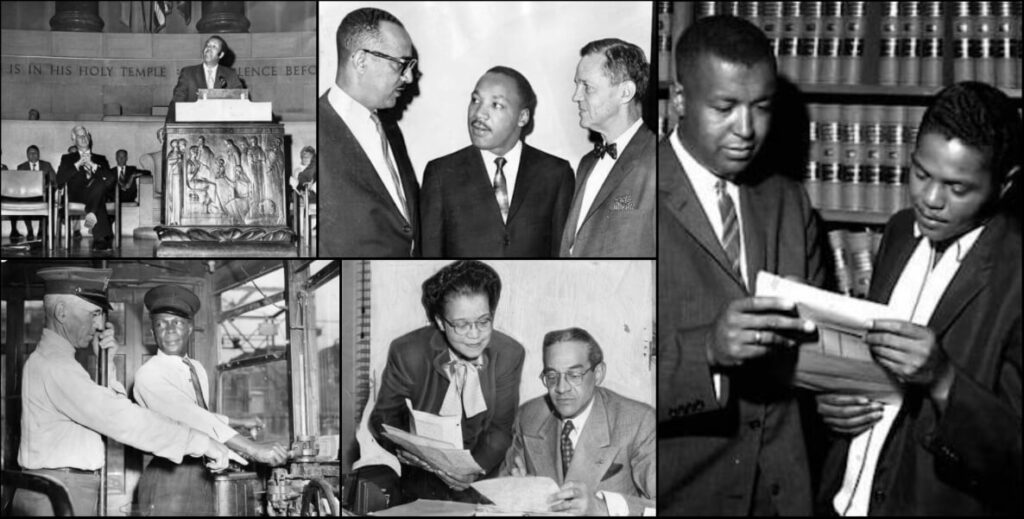

The first African American trained by P.T.C. | Photo courtesy Temple Urban Archives

1925

-

- National Bar Association is founded by George Woodson, a Black lawyer from Iowa. That year, there are 1,223 Black lawyers in the country, of whom 24 are women. Washington, D.C. has the largest number of lawyers — 225 — but many were called “sundowners” because they mostly practiced in the evenings after they completed their daytime jobs working in the government.

1927

-

- Sadie T. M. Alexander, (1898-1989) becomes the first Black woman to graduate from Penn law school. She is elected to the Law Review in spite of efforts of the law school dean, Edward Mikell, to prevent her from serving. (His opposition to her election may have been based on her gender, since a Black man was elected at the same time.) Alexander goes on to become the first Black woman admitted to the Pennsylvania Bar and is the only Black woman lawyer in Philadelphia until 1949.

- The Raymond Pace Alexander Law Office consists of Alexander, John Francis Williams, Lewis Tanner Moore, Maceo Hubbard and Sadie T. M. Alexander. The practice at 19th and Chestnut streets is unique for the time because it has four Ivy League-trained lawyers and is said to be the largest “Black law firm” in the country.

1928

-

- ⚡️ Aloyisus Leon Higginbotham, Jr. is born in Trenton, New Jersey. The unique spelling of his first name is the result of his father’s name on his birth certificate. He was the only child of Aloyisus Sr. and Emma Douglas Higginbotham.

- John C. Asbury (1862-1941), an 1884 graduate of Howard Law School, becomes the first Black lawyer to serve as an assistant district attorney in Philadelphia. Asbury also works as an assistant city solicitor from 1916 to 1920 and as member of Pennsylvania House of Representatives from 1921 to 1925.

1929

-

- Louis L. Redding (1902-1998), a 1928 graduate of Harvard Law, is the first Black admitted to the Delaware State Bar and the only Black lawyer in the state for 25 years. In the 1950s, Redding represents clients in two school desegregation cases in Delaware that serve as forerunners for Brown v. Board of Education, which he later argues along with the legal team headed by future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall.

1930

-

- Thurgood Marshall (1908-1993) graduates from Lincoln University. Three years later, he graduates from Howard Law magna cum laude.

1931

-

- Nine Black teenagers, “The Scottsboro Boys,” are falsely accused and convicted of the rape of two White women in Alabama.

1935

-

- Pennsylvania passes the second Equal Rights Law after vigorous advocacy by Raymond Pace Alexander and others.

1937

-

- William H. Hastie (1904-1976) is appointed as U. S. District Court Judge for the Virgin Islands, becoming the first Black to serve on the federal bench. The first Black judges appointed in the continental U.S. are James B. Parsons in Illinois and Wade H. McCree, Jr. in Michigan, both in 1961.

- Between 1937 and 1976, only 37 Blacks serve as federal court judges. Only one of them is a woman, Constance Baker Motley, of New York, who was appointed in 1966.

- Fitzhugh Lee Styles authors Negroes and the Law, the first book on the history of Black lawyers.

1938

-

- Crystal Byrd Fauset (1894-1965) is elected to Pennsylvania House of Representatives, becoming the first Black woman elected to a state legislature in the U.S.

- In Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, the U.S. Supreme Court rules that Missouri violated the Equal Protection Clause by denying law school admission to Black students, and instead offering to pay their tuition at an out-of-state law school. This was the first of several cases of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund’s litigation strategy to overturn racial discrimination in education that resulted in the Brown v. Board of Education victory.

- The other cases are: Sipuel v. Oklahoma (1948), in which the Court ordered the state to admit Blacks to the state law school rather than a segregated Black law school; McLaurin v. Oklahoma (1950), in which the Court ruled that requiring Black students to take classes in a separate room at the White university violated the Equal Protection Clause; and Sweatt v. Painter (1950), in which the Court ordered that the Black plaintiff be admitted to the University of Texas Law School after he refused to attend a Black law school established by the state.

1941

-

- Of 58 Black women lawyers practicing in the U.S., Sadie Alexander is the only one in Philadelphia. Between 1933 and 1943, zero Blacks of any gender pass the Pennsylvania Bar. In the decade prior, only 13 pass the bar. This low tally later results in multiple investigations into racial discrimination in the bar exam.

- Executive Order 8802 is signed by President Roosevelt to prohibit racial discrimination in the national defense industry, after A. Philip Randolph threatened a mass demonstration in Washington. It is the first executive order to promote equal opportunity and prohibit employment discrimination in the U.S. Roosevelt establishes the Fair Employment Practices Commission.

- Of 58 Black women lawyers practicing in the U.S., Sadie Alexander is the only one in Philadelphia. Between 1933 and 1943, zero Blacks of any gender pass the Pennsylvania Bar. In the decade prior, only 13 pass the bar. This low tally later results in multiple investigations into racial discrimination in the bar exam.

1944

-

- ⚡️At the age of 16, Higginbotham graduates from Ewing Park High School in Trenton. That fall, he begins studying engineering at Purdue University, where Higginbotham and 11 other Black students are housed in an unheated, barracks-style attic apart from the dormitories on campus. Higginbotham arranges a meeting with Purdue President Edward Charles Elliot to demand better living conditions. Elliot refuses, and tells Higginbotham to leave the university if he cannot accept those conditions.

1945

-

- ⚡️ Higginbotham transfers to Antioch College, where, after his experience at Purdue, he decides to study pre-law. Coretta Scott (later Coretta Scott King) is admitted into Antioch the same year; they are the only three Black students in their class.

-

1946

- 29 Black lawyers practicing in Philadelphia. All but seven of these lawyers’ offices are located in a 7-square block radius, south of Market Street between 19th and 12th streets. Most of these offices were on either South 15th or South 16th Street.

- William T. Coleman, Jr. elected to Harvard Law Review and graduates first in his class; in 1948, he becomes first Black to serve as a United States Supreme Court law clerk.

1947

-

- Herbert E. Millen (1892-1959) becomes the first Black judge in a court of public record when he is appointed as a Philadelphia Municipal Court Judge.

- Juanita Kidd Stout (1919-1998) graduates from Indiana University law school and receives an LL.M in 1954. In 1942, she is hired as a secretary for Charles Hamilton Houston in the Washington, D.C. firm of Houston, Houston & Hastie. She studies law in the evenings at Howard Law School for one year before transferring to Indiana. When William H. Hastie is appointed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, she becomes his administrative assistant.

- Philadelphia adopts the Fair Employment Practices Ordinance.

1948

-

- ⚡️Higginbotham graduates from Antioch before entering Yale Law School in 1949.

1950

-

-

The Barristers’ Association emblem William H. Hastie is appointed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, becoming the first Black federal appellate court judge in the U.S.

- Barristers’ Association of Philadelphia (a Black lawyers group) is founded by Curtis Carson, Thomas Reed, Robert Williams, Charles Wright and Arthur Thomas, who is elected as its first president.

-

1951

-

- ⚡️ In Yale’s Harlan Fiske Stone National Moot Court Competition, Temple Law School’s team, led by Clifford Scott Green (1923-2007) defeats Yale’s team — led by Green’s future law partner and judicial colleague A. Leon Higginbotham, Jr. Green graduates from Temple Law as a member of the Law Review and third in his class. He passes the Pennsylvania Bar exam with the highest grade in the state.

- Philadelphia Home Rule Charter is adopted, making Philadelphia the first in the nation to include a ban on racial and religious discrimination in City employment, services, and contracts. Sadie T. M. Alexander is the principal drafter of this provision.

- Clifford Scott Green (1923-2007) graduates from Temple Law School, as a member of the Law Review, 3rd in his class, and passes the Pennsylvania bar exam with the highest grade in the state.

PART II: Higginbotham and His Contemporaries (1952-1962)

1952

-

- For the first time in more than 70 years, the Tuskegee Institute reports that there were no lynchings in the U.S.

- ⚡️ Higginbotham graduates from Yale Law School.

- ⚡️ Green, Schmidt & Harris firm founded when Clifford Scott Green and Harvey Schmidt formed a partnership; they are joined by Doris Mae Harris and A. Leon Higginbotham in 1954. Austin Norris and William H. Brown, III join the firm in subsequent years and it becomes Norris, Schmidt, Green, Harris, Higginbotham & Brown. Over the years, other lawyers included: Herbert Hutton, William Hall and Robert W. Williams, Jr. who became state or federal judges; and Ira. J.K. Wells, Mansfield Neal, Edward Nichols, Ronald Davenport, Hardy Williams, Arthur F. Early, Prather Randall, Germaine Ingram, Frank Williams, Robert Paskins and Walter A. Gay, Jr., Timothy Jenkins.

- William T. Coleman, Jr. becomes the first Black associate and then the first Black partner in a large White law firm (Dilworth, Paxon). He also later serves on the staff of the Warren Commission that investigated the assassination of President Kennedy.

1953

-

- ⚡️Higginbotham joins the Philadelphia District Attorney’s office as an Assistant District Attorney. He is one of five Black ADAs in the office: Curtis Carson, Thomas Reed, Isaiah Crippins and Edward K. Nichols, Jr.

- The Hastie Committee is appointed to investigate racial discrimination in the bar examination and admissions procedures after Philadelphia lawyer J. Austin Norris claims that the exam discriminates against Black applicants. The committee consists of Abraham L. Freedman, G. Ruhland Rebmann, Jr., Theodore G. Spaulding, and William H. Hastie. A year later, the Hastie Committee reports that it “has made a complete investigation and there are no discriminatory practices.”

- Coleman and Raymond Pace Alexander file a petition seeking an order to admit Black students to Girard College. The matter ultimately reaches the U.S. Supreme Court, which holds that the Board of City Trusts, a government agency, could not discriminate on the basis of race. On remand, the Philadelphia Orphans’ Court appoints private trustees, and the college refuses to admit Blacks.

- Villanova Law School opens.

1954

-

- Brown v. Board of Education holds that “separate but equal” facilities in public accommodations violate the U.S. Constitution. Philadelphia lawyer William T. Coleman, Jr. serves as co-counsel for the petitioners.

1956

-

- Southern Manifesto, issued by 100 Southern senators and representatives, denounces Supreme Court decisions prohibiting segregation in public schools.

- Arneda Jackson Hazell (1917-2001) becomes the first Black woman to graduate from Temple Law School. Hazell goes on to practice with Hazell and Bowser from 1957 to 1988.

1957

-

- Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) founded by Martin Luther King, Jr. and other members of the Montgomery Improvement Association who lead the successful boycott in Montgomery, Alabama.

- Civil Rights Act of 1957 passes. The first legislative act protecting the rights of Blacks since Reconstruction, it establishes the Civil Rights division of the Justice Department, allowing federal prosecutors to get court injunctions to prevent interference with the right to vote. Also creates the Federal Civil Rights Commission.

1958

-

- Robert N.C. Nix, Sr., a Penn law school graduate, becomes the first Black elected to U.S. Congress from Pennsylvania.

- William T. Coleman, Jr. and Raymond Pace Alexander argue before the Pennsylvania Supreme Court that the will of Stephen Girard creating Girard College violated the U.S. Constitution. The Court upholds the will.

- A. Benjamin Johnson is the first Black graduate of Villanova Law School.

1959

-

- Raymond Pace Alexander appointed first Black Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas judge and is elected to a full 10-year term.

- Juanita Kidd Stout appointed to Philadelphia Municipal Court and is elected to a 10-year term, becoming the first Black woman elected to a court of record.

1960

-

- ⚡️At age 32, Higginbotham is named president of the Philadelphia chapter of the NAACP.

1961

-

- Executive Order 10925, issued by President John F. Kennedy, requires government contractors to “take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed and that employees are treated during employment without regard to their race, creed, color, or national origin.” The President’s Commission on Equal Opportunity, the forerunner to the EEOC, is established.

- Freedom Rides: Black and White civil rights activists ride interstate buses into the segregated Southern states to protest the failure of these states to enforce two U.S. Supreme Court decisions ruling that segregated buses were unconstitutional.

- Thurgood Marshall is appointed to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals by President Kennedy.

Part III: Higginbotham’s Jurisprudence, Scholarship and Public Service (1962-1998)

1962

-

- ⚡️ President Kennedy appoints Higginbotham to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), making him the first Black member in the history of the body, and the youngest person to ever be named a FTC commissioner.

- James Meredith, amid rioting by Whites that results in two deaths, integrates the University of Mississippi.

- Baker v. Carr holds that federal courts could review state legislative apportionment plans to ensure that Black voters are fairly represented: “One man, one vote.”

1963

-

- Birmingham Boycott led by Dr. Martin Luther King results in the arrest of hundreds of Black protesters. The boycott gains international public attention when Bull Connor, the police commissioner, uses high-powered fire hoses and police dogs to disburse the marchers, who are mostly high school students. This incident and other racial violence motivate President Kennedy to push for the enactment of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

- The 16th Street Baptist Church bombing: The Ku Klux Klan bombs a Black church in Birmingham, Alabama, resulting in the death of four young girls attending Sunday school: Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson and Denise McNair.

- March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

- Vivian Malone and James A. Hood integrate the University of Alabama in spite of Governor George C. Wallace’s publicity stunt of blocking the door and vowing, “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”

1964

-

- Civil Rights Act passes, outlawing discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. It requires equal access to public places and employment and enforces desegregation of schools and the right to vote.

- ⚡️ Higginbotham is appointed a federal judge by President Lyndon Johnson, becoming the first Black judge to serve in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania.

1965

-

- Voting Rights Act passes.

- Malcolm X assassinated.

- Selma to Montgomery March.

- Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is created, pursuant to a mandate of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

1966

-

- Constance Baker Motley becomes the first Black woman appointed to a federal district court.

1967

-

- Thurgood Marshall is appointed the first Black U.S. Supreme Court Justice by President Johnson. Marshall has served as director counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and, along with Charles H. Houston, was the principal architect of the legal strategy that resulted in the Brown decision. He successfully argued numerous other cases on a wide array of equal access and racial discrimination issues. He won 29 cases before the U.S. Supreme Court. As the first Black U.S. Solicitor General, he won 14 of the 19 cases he argued for the government before the Supreme Court.

- Loving v. Virginia decided by the U.S. Supreme Court, concludes that states can not ban interracial marriages, and that such acts violate the Equal Protection Clause.

- Theodore O. Spaulding (1902-1974) is first Black elected to a Pennsylvania Appellate Court, Superior Court — and the first Black to be elected to statewide office.

1968

-

- ⚡️ Higginbotham and the rest of the Kerner Commission release a report condemning racism as the primary cause of the recent surge of riots. (President Johnson had appointed the commission in July 1967 to uncover the causes of urban riots and recommend solutions.) The report identifies more than 150 riots between 1965 and 1968, blames “White racism” for sparking the violence, and concludes that “our nation is moving toward two societies, one Black, one White — separate and unequal.” It warms of “continuing polarization of the American community and, ultimately, the destruction of basic democratic values.”

- Martin Luther King Jr. is assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, resulting in 200 race riots around the country.

- Council on Legal Education Opportunity (CLEO) is founded in Virginia to expand opportunities for minority and low-income students to attend law school. More than 10,000 students go on to participate in CLEO’s programs and join the legal profession.

- U.S. Supreme Court refuses to hear an appeal of the Third Circuit’s affirmation of District Court Judge Joseph S. Lord’s ruling that the segregationist provisions of Stephen Girard’s will were unenforceable as violations of 14th Amendment Equal Protection. The Board of Trustees of Girard College votes to admit Black students. A crowd of over 600 holds a victory rally at the school. This ruling ends a 15-year challenge to the will that included 14 lawsuits.

- Civil Rights Act of 1968 is passed by Congress, banning discrimination in housing sales and rentals.

- William H. Brown, III, is appointed to the EEOC and becomes chairman in 1969.

1969

-

- National Conference of Black Lawyers is founded.

1970

-

- Norris and Ricardo C. Jackson, President of the Barristers Association, argue that the Pennsylvania Bar examination process discriminates against Black lawyers and threaten to take legal action. Norris has been consistently arguing that the bar examination process was discriminatory since the Hastie Committee report in 1953.

- Special Committee on Pennsylvania Bar Admission Procedures (Liacouras Committee) is appointed by Philadelphia Bar Association Chancellor Robert Landis to investigate discrimination in the bar examination. The committee — comprised of future Temple University President Peter J. Liacouras, Clifford Scott Green, Ricardo C. Jackson, Paul Dandridge, and W. Bourne Ruthrauff — concludes that the bar exam “as developed and administered is invalid and discriminatory and circumstantial evidence leads to a strong presumption that Blacks are indeed discriminated against when they take the exam.” When Liacouras and the Committee’s counsel, Robert Reinstein, seek to have the report published in the Temple Law Quarterly, the dean, Ralph Norvell, tries to block it by threatening to refuse to issue the required “moral fitness” certification the student editors needed to qualify for the Pennsylvania Bar. The law faculty intervenes to support the students; the report is published.

- Norris and Ricardo C. Jackson, President of the Barristers Association, argue that the Pennsylvania Bar examination process discriminates against Black lawyers and threaten to take legal action. Norris has been consistently arguing that the bar examination process was discriminatory since the Hastie Committee report in 1953.

1971

-

- Clifford Scott Green is appointed to the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District.

- Doris Mae Harris is appointed to the Court of Common Pleas.

- Hardy Williams (1931-2010), a 1957 graduate of Penn Law School, runs for mayor. Twelve years later, Wilson Goode, who managed Williams’ campaign, is elected Philadelphia’s first Black mayor. Williams serves as a Pennsylvania legislator for 28 years.

1972

-

-

- Robert N.C. Nix, Jr. becomes the first Black elected to the PA Supreme Court.

-

1974

-

- ⚡️ Higginbotham issues a famous ruling in Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Local 542, (International Union of Operating Engineers). The case revolves around 12 Black plaintiffs accusing the union of racial discrimination. When the defendant attempts to get Judge Higginbotham removed from the case on account of his race, arguing he’d be biased, Higginbotham’s forthright opinion establishes important legal precedence:

“[T]hey are arguing that a Black judge cannot convince some Whites that he possesses the requisite impartiality unless he shuns associations of black scholars and, a fortiori, never speaks to them. Thus by the subtle tone of their objection, they demonstrate either that they want Black judges to be robots who are totally isolated from their racial heritage and unconcerned about it, or, more probably, that the impartiality of a Black judge can be assured only if he disavows, or does not discuss, the legitimacy of blacks’ aspirations to full first class citizenship in their own native land.”

1977

-

- ⚡️Higginbotham is appointed by President Jimmy Carter to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. He serves as chief judge from1990 to 1991.

1978

-

- ⚡️ Higginbotham publishes In the Matter of Color: Race in the American Legal Process.

1980

-

- Joseph E. Coleman (1922-2000) becomes the first Black man elected as President of Philadelphia City Council. Coleman, a Mississippi native who was trained as a chemist, had graduated from Temple Law School in 1963.

- Philadelphia City Council adopts the Minority Business Enterprises Ordinance over a veto by Mayor William Green, Jr. The ordinance requires companies seeking City contracts for the provision of goods and services use their best efforts to utilize minority companies in performing the contracts. Council also creates the Minority Business Enterprises Council (MBEC) to monitor compliance.

1981

-

- Philadelphia Chapter of the National Bar Association Women Lawyers Division is formed by Lydia Kirkland, Angela Nolan and Beverly Williams. Fifty Black women lawyers attended the first planning session at Temple Law School.

1982

-

- ⚡️ Higginbotham is interrogated by police in South Africa after arriving to consult a South African Black lawyers association in legal efforts to end apartheid. Higginbotham spends more than a decade working on these efforts, and is personally requested by Nelson Mandela himself. “Judge Higginbotham’s work and the example he set made a critical contribution to the course of the rule of law in the U.S. and a difference in the lives of African Americans, and indeed the lives of all Americans,” says Mandela. “But his influence also crossed borders and inspired many who fought for freedom and equality in other countries.”

1983

-

- W. Wilson Goode is elected as the first Black mayor of Philadelphia.

1984

-

- Robert N.C. Nix, Jr. becomes the first Black Chief Justice of the PA Supreme Court.

1985

-

- MOVE bombing. A Black compound in West Philadelphia is bombed by the Philadelphia Police Department, killing 11 occupants of the building and destroying 60 homes in the neighborhood.

- U.S. Court House and Post Office building is renamed the Robert N. C. Nix Sr. Federal Building and Post Office.

1988

-

- Juanita Kidd Stout is appointed to PA Supreme Court, becoming the first Black woman in the country to serve on a state supreme court.

1990

-

- ⚡️ Higginbotham is named chief judge of the Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit.

- ⚡️ Nelson Mandela is released from prison after 27 years. Higginbotham meets with Mandela to help create the South Africa Free Election Fund and assists him in drafting the country’s new constitution. Mandela, in describing Higginbotham’s contributions, says, “Judge Higginbotham’s work and the example he set made a critical contribution to the course of the rule of law in the U.S. and a difference in the lives of African Americans, and indeed the lives of all Americans. But his influence also crossed borders and inspired many who fought for freedom and equality in other countries.”

1991

-

- Clarence Thomas (1948- ), a graduate of the College of the Holy Cross and Yale Law School, is appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

- ⚡️ Higginbotham publishes An Open Letter to Justice Clarence Thomas from a Federal Judicial Colleague, in which he excoriates the newly minted Supreme Court justice (and the second Black American to serve on the court) for his opposition to affirmative action and the perceived failure to embrace a legacy of civil rights that paved the way for his nomination:

I suggest, Justice Thomas, that you should ask yourself every day what would have happened to you if there had never been a Charles Hamilton Houston, a William Henry Hastie, a Thurgood Marshall, and that small cadre of other lawyers associated with them, who laid the groundwork for success in the 20th-century racial civil rights cases. If there had never been an effective NAACP, isn’t it highly probable that you might still be in Pin Point, Ga., working as a laborer as some of your relatives did for decades? The philosophy of civil rights protest evolved out of the fact that Black people were forced to confront this country’s racist institutions.

1993

-

- ⚡️ Higginbotham retires as a federal judge and joins the New York law firm of Paul, Weiss and the faculty at Harvard University.

1994

-

- The new Philadelphia justice center is named the Juanita Kidd Stout Justice Center.

1995

-

- ⚡️ Higginbotham receives the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Bill Clinton.

1996

-

- ⚡️ Higginbotham’s Shades of Freedom: Racial Politics and Presumptions of the American Legal Process is published.

1998

-

- ⚡️ Higginbotham, in his final public appearance, testifies at Clinton Impeachment Hearing, saying that Clinton’s alleged perjury did not justify impeachment:

I submit that as to impeachment purposes, there is not a significant substantive difference between the hypothetical traffic offense and the actual sexual incident in this matter. The alleged perjurious statements denying a sexual relationship between the President of the United States and another consenting adult do not rise to the level of constitutional egregiousness that triggers the impeachment clause of Article II.

-

- ⚡️ Higginbotham dies at age 70. Among those who memorialize him is civil rights leader Jesse Jackson: “What Thurgood Marshall and Charles Hamilton Houston were to the first half of this century, Judge Higginbotham was to the second half.”

MORE FROM OUR COLOR OF LAW SERIES HONORING LEON HIGGINBOTHAM