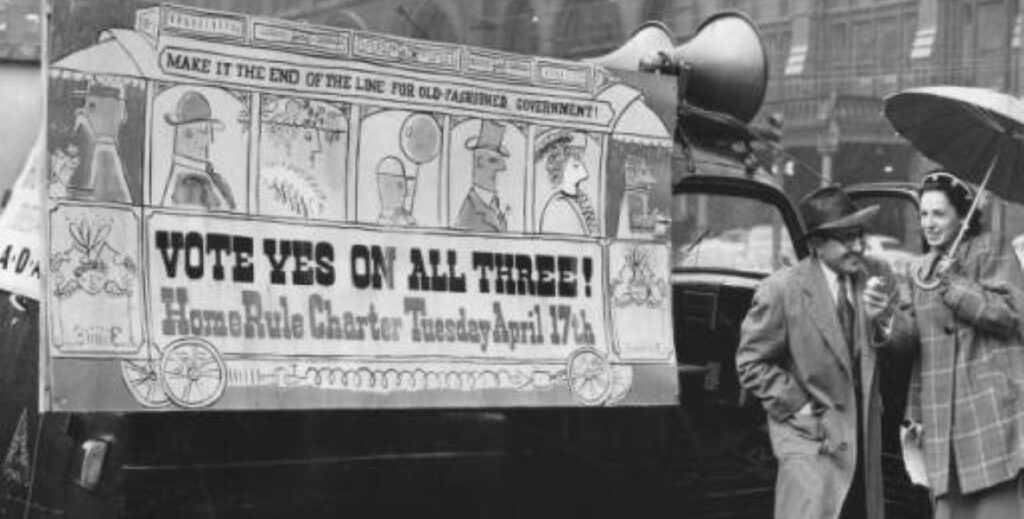

Philadelphia’s Home Rule Charter: Sounds like something vaguely 17th-century-ish that William and Hannah Callowhill Penn dreamed up for their “Greene Countrie Towne,” or their “green country town,” et al. In fact, the Home Rule Charter is our City’s constitution, our government’s ground rules, first created in 1951 to help weed out political corruption and reform City Hall.

Wonder how that worked out? Kidding. It worked, at first. And then, well, politicians have ways of getting around pesky Home Rule Charters and such.

More than 70 years ago, Philly’s Home Rule Charter established a framework that Philadelphians who’ve been elected to office (think: Mayor, City Council, City Controller) or employed by the City (department heads, School District staff, sanitation workers) — must exist in. Some insiders believe the Charter to be entirely essential. Others feel it’s increasingly irrelevant.

Citizens have the chance to change the Home Rule Charter by voting on referendums to amend it via ballot questions (lately, during virtually every election cycle). In other words, Philadelphia’s Home Rule Charter is, writes The Citizen’s Jemille Q. Duncan, “a law’s law, just like the state Constitution.” Fun, right?

Maybe for some. Most of us taking a look at the Home Rule Charter for the first time might describe it as … long. Or complicated. Perhaps: full of annotations and this symbol: §, which, on its face, is as off-putting as language symbols get. Others might find it … quirky. Or, a tad rando.

No offense to any policy nerds out there, but the Home Rule Charter also reads boring-er than boring. It’s the kind of document politicians and lawyers create in order to make things work, but that’s written and presented in a way that only they can understand them.

Huzzah for accessibility! said no writer or amender of legislation, ever.

What does our Home Rule Charter say (that you care about)?

Here’s one: It prevents City workers from working on political campaigns.

Another: An elected city official can’t run for another office without resigning their current office first. This is why members of City Council have to resign from their posts in order to run for mayor. We now call this the “Resign to Run” law.

The idea behind the Home Rule Charter was to make City workers do what’s in the best interest of the city, not their political ambitions, or careers, or wallets, or sister’s friend’s father-in-law’s plumbing company. It’s supposed to keep things straight. One way it attempted this was by putting lots of power in the hands of the mayor, who could serve only two terms. The creators of the Home Rule Charter called this a “Strong Mayor System.”

What does it say that seems slightly to-all-out absurd?

One way to amend the charter is to have citizens vote on it. Writes The Citizen’s Larry Platt, “when [City] Council is unable to convince the mayor through the regular political process to do something, it reverts to a Charter amendment to get it done.”

For example, the Home Rule Charter says the mayor is the only person in City Hall who can hire for new City positions. So, when City Council wants to establish a force of Public Safety Enforcement Officers, and the mayor’s not onboard, they put it on the ballot and … the vast majority of times, it gets passed. (Doesn’t matter that in the voting booth might be the first time you read about this new law. According to research, chances are if it’s a ballot question, you’re voting, Yes.)

On the other hand, the Home Rule Charter also contains additions that seem, well, wholly unrelated to how government, including law enforcement, work, or how the city is run — or impossible for the City to implement, seeing as Philadelphia’s laws are subordinate to that of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania’s and the United States of America’s.

For example, in November 2020, the Charter was amended to “eliminate the practice of unconstitutional stop and frisk,” which would seem to be pointless. While stop and frisk itself is legal, any unconstitutional deployment of it is, um, already unconstitutional. Or, in May 2019, when the Charter was amended to “call upon the Pennsylvania General Assembly to raise the Pennsylvania minimum wage now, so that it reaches $15 an hour, in stages, by 2025.” OK. Well, duly noted. Harrisburg thanks you.

In other words, while many Charter amendments get things done, creating new departments, combining others, others are performative, more about making a statement than making a change.

Why do some people want to rewrite the damn thing?

We here at The Citizen were among those people! In early 2020, we convened a group of graduate students and citizens at Drexel University for a class led by politics professor Richardson Dilworth, grandson of the legendary mayor who led the crafting of the original charter. The intention was to explore the history of the charter, how it applies to our modern city — and then make recommendations for revising it to fit who we are now.

In part, we were inspired by the 2019 election in New York City, in which voters ushered in major changes to their city’s charter — including making it the first big city to enact ranked choice voting for their primaries and special elections. As Platt wrote a month later:

1951’s Charter was a visionary document, a love letter to good government. But it is nearly 70 years old; much of it is outdated. Which is why we ought to follow New York’s lead and update it.

The last time our Home Rule Charter was put to review by a Charter Commission was 1991. That did not result in significant changes. Reformers of all political backgrounds and beliefs have long argued for revamping the Charter now, in order to make the kinds of changes that hew to the original intent of the document — better government.

Some have called, for example, for eliminating City Council members’ participation in DROP, a Deferred Retirement Option Plan, a plan originally intended for civil service, but that basically lets our electeds double-dip on their salary.

Platt laid out his personal wish list:

Open primaries, so more Philadelphians can have a say in who runs Philadelphia [though this may require state approval to actually enact]; term limits for City Council, given that we’re the only big city in America that has them for the mayor but not for our legislative body; the elimination of row offices and councilmanic prerogative; and the establishment of an elected public advocate, as in New York — in a corrupt, one-party town, maybe we need to codify a good government elected office, with subpoena power and a non-voting seat on Council.

These are some of the recommendations that came out of the Drexel class, as well. Others included staggering City Council terms; mandating the Council president is an At-Large member, elected by the whole city; giving non-naturalized immigrants the right to vote; and electing everyone who makes any decisions for the city — from school board to police advisory commission.

Dilworth himself suggested something that gets back to what may be the document’s fundamental flaw: Its unreadability.

“A fundamental charter reform should be rewriting the thing so that its language is accessible — and perhaps even inspirational, like the U.S. Constitution,” he says. “The charter should be made accessible by shortening its length to include only constitutional issues — that is, it should be the rule book that decides how the City makes rules, and really nothing else.”