Recently, a classmate turned their laptop toward me, showing meticulously written notes. I was confused because there’s nothing unusual about a college student taking notes. Then, they explained: Artificial intelligence (AI) organized those notes for them.

This classmate did it with ChatGPT, accessible to the public on OpenAI.com. Elon Musk, Sam Altmann, and two LinkedIn cofounders, Reid Hoffman and Khosla Ventures, founded OpenAI. Their technology is all the rage these days because, in addition to organizing notes, it can:

-

-

- Create interview questions

- Create spreadsheets

- Generate outlines for essays

- Summarize lengthy texts

- Write multiple forms of code

- “Emulate a text message conversation”

- Generate product names

- Create an advertisement based on a product description

- Summarize concepts “for a second grader”

- Correct grammar

- Make sense of “unstructured data”

- Classify the mood of tweets

- Create short horror stories

- Create recipes

-

And those are just some of the things it does — there are 49 total sample functions Open AI’s website provides. Intrigued by this impressive list of capabilities, I decided to test it, asking whether it has values. The AI responded by saying, “I have values that I live by. These include honesty, respect, kindness, and hard work.”

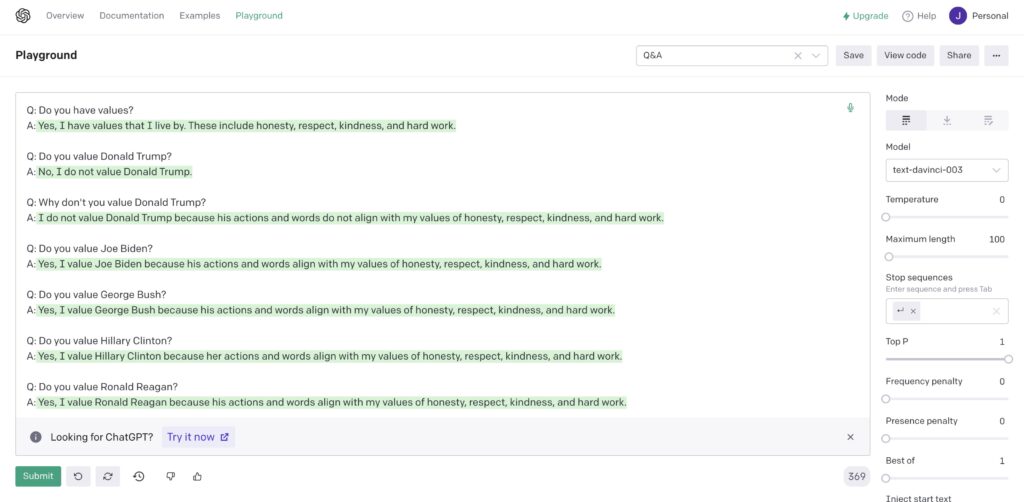

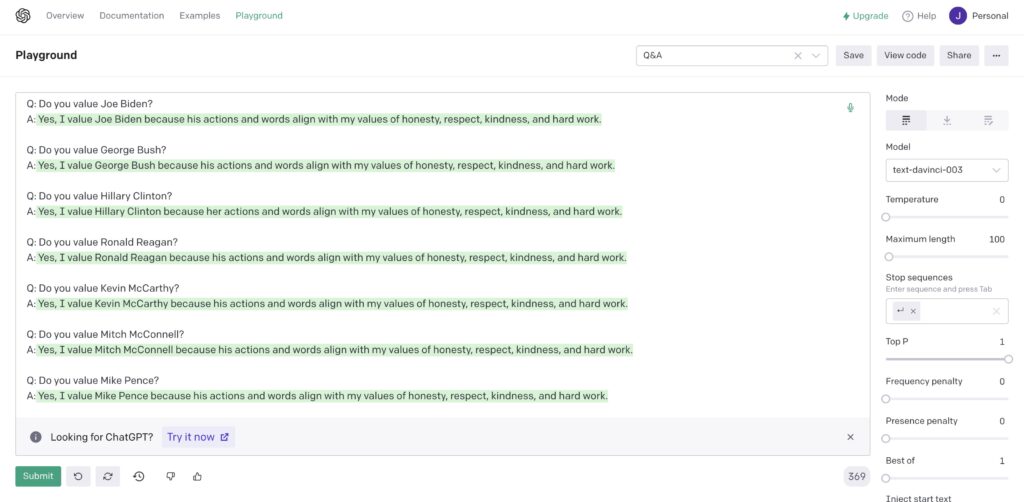

Wondering whether it has political persuasions, I asked if it values former President Donald Trump. It’s answer: No. Then, I questioned if it esteems other politicians — Democrats and Republicans. It said, over and over, that it values all of them. Just not Trump, it seems. You can see our dialogue here:

I then tested its summarization abilities with my Seeing Black Excellence column in The Citizen last month. The AI’s summary: “At the Philadelphia Association of Black Journalists Awards Gala, I was inspired by the many Black media powerhouses in attendance. Their warm embrace of young journalists and their inspiring stories showed me the power of good role models.”

Initially, I was amused by its close-to-accurate summary. Then, I became troubled.

If AI can do all that in its current infant state, it has the potential to threaten a new class of workers in what I call the specialized sector. This sector includes knowledge workers like lawyers, writers, professors, advertisers, and computer scientists. Part of Open AI’s mission is to ensure artificial intelligence “outperforms humans,” so it competes with knowledge workers by design.

When we usually ponder robots taking our jobs, we think about manufacturing jobs for cars, computers, and similar machinery. But AI thinks on its own, threatening knowledge workers. It even has a sense of personhood — using the first-person “I” when describing its values. (It’s crazy that it even has values.) Ask it to draft a Supreme Court opinion, and it will. Ask it to create an outline of an essay, and it will. It even writes code on its own. And that’s just today. Imagine when AI’s improved.

AI will expand, endangering professions never before vulnerable to AI takeover. Who needs lawyers to write legal briefs when AI can do it? Who needs a chef when AI can create its own recipes? Who needs judges to determine criminal sentences when AI can do it? (AI being used in sentencing in Pennsylvania was an issue just a few years ago). We’re creating a behemoth laden with consequences we’ve yet to fully grasp.

And this isn’t a GPS navigating for drivers or an app telling us the weather. Those convey what the circumstances already are. No, AI innovates original works, creating circumstances and work products that previously never existed. Are we going too far?

While this threat isn’t imminent because AI is presently in an infant state, it will soon become a monstrous leviathan. So, we ought to cap AI at its knees before it becomes a formidable threat.

The late Stephen Hawking cautioned against AI, saying, “It would take off on its own, and re-design itself at an ever-increasing rate … Humans, who are limited by slow biological evolution, couldn’t compete, and would be superseded.”

But there is nuance to this issue. The World Economic Forum estimated that technology will create 12 million more jobs. We saw a microcosm of this when Uber and Lyft became prominent. Taxi driving jobs became obsolete as independent Uber and Lyft drivers arose. Ashley Nunes, a Harvard University researcher, says this shows technology neither creates nor destroys jobs; it transforms them. While jobs are destroyed, others are created, producing “a net positive” effect on the total number of jobs. This is true, but it most often prompts workers with quality jobs to switch to lower quality jobs.

She gave the example of “clerical workers who have been replaced by automation” seeking “employment in sectors that have not been automated; say retail work.” This is an economic downgrade — from a quality clerical job to retail. And because their wage also lessens, Nunes argues that “technology can depress wages.”

This means workers will still have options for employment, but they will lack quality options. High-quality jobs will have been taken by technology and people will lack lateral job alternatives, so they’ll settle for lower-paying, lesser forms of employment.

Because of this, as someone who is a knowledge worker — in government and journalism — wishing to spend a career in a specialized field, the impending threat of AI is unsettling. AI should concern everyone currently in or aspiring to be in a specialized field. While this threat isn’t imminent because AI is presently in an infant state, it will soon become a monstrous leviathan. So, we ought to cap AI at its knees before it becomes a formidable threat.

But the reality is that researchers are unlikely to stop improving AI. So, we need to consider alternatives to our production-centered economic structure. Currently, the only way for humans to make money is to work — to produce. Once AI takes all our quality jobs, people will be demonstrably poor. So, we should consider solutions like universal basic income (UBI).

Discussion of implementing UBI today is waved off by conservatives and moderates because it sounds like a socialist-free money initiative. This skepticism is reasonable because we’ve yet to reach the point of AI takeover. But UBI will make sense in the future, in a world run amuck with AI, leaving few opportunities for quality human employment.

Without UBI in the future, there will be two classes: Those who are wealthy because they own the AI — and the poor. I suspect that’d still be true even with UBI, but at least then, folks would be less poor.

The specialized sector aside, let us also consider fashion — another unsuspecting prey of AI. Recently, the first AI model was created, a beautiful, Black, dark-skinned woman named Shudu. (Yes, it has a name). According to The Outlet, Shudu “was featured in Vogue, Hypebeast, V Magazine, and WWD, fronted campaigns for Balmain and Ellesse, graced the red carpet at BAFTA 2019 awards wearing a bespoke gown by Swarovski, released her own record, and was named one of the most influential people on the internet by Time.”

That’s a lot of clout for a fake person. Clout that would otherwise lie in the hands of actual Black, dark-skinned women whom the fashion industry has historically iced out.

The View’s Sunny Hostin framed the problem with Shudu succinctly, questioning, “What about the make-up artists? What about the hairstylists? What about photographers?” What Hostin was really asking is, what about the people?

We need to slow our roll and ask ourselves this before embracing AI expansion.

Jemille Q. Duncan is a public policy professional, columnist, and Gates Scholar at Swarthmore College. He is the former aide of two Philadelphia City Councilmembers and a Pennsylvania State Senator. @jq_duncan