There are places in Philadelphia and across the country where you can find large groups of people addicted to drugs. But if you’re looking for the highest concentration of Americans with substance use disorders, look at detention centers. Drug addiction among the general U.S. population is 16.5 percent. Addiction among the incarcerated U.S. population is four times that, 65 percent.

It would follow that if you wanted to help more people recover from addiction — to truly rehabilitate them — jails and prisons would be a good place to start.

For 30 years, Philadelphia has been somewhat of a leader in this pursuit. That’s how long our city jails (not prisons, jails) have offered addiction treatment. For half of those years, these facilities have also allowed incarcerated people suffering from arguably the worst of all drug addictions — opioids — to continue treatment with life-saving, harm-reducing medications.

“It’s actually a beautiful program. I don’t know how I would’ve gotten through without it. I don’t have any desire to get high. The only desire I have is to do better.” — Crystal Quigley

We’ll get into how the treatment works in a minute. Suffice it to say, by all accounts (and there aren’t too many) the program has been a success. Every year, the Philadelphia Department of Prisons (PDP) continued anti-addiction medication regimes for 500 offenders — and since 2017, the PDP started new medications for 3,000 more annually. A study of Philly’s women’s facility found 40 percent continue treatment following release.

Then, the thing that worsened the opioid epidemic — Covid — also weakened the PDP’s Opportunities for Prevention and Treatment Interventions for Offenders Needing Support (OPTIONS) program. While residents of Philly jails receiving addiction treatment could still access (and do access) medications, dedicated housing, pre-release services, even college-level classes, they no longer received cognitive behavior therapy, an essential ingredient in the recovery mix. This year, the PDP is starting to restore this offering. Without it, the program is incomplete.

With it, Philadelphia can get back to being a model for the rest of the state, like Denver is for Colorado, where they recently passed a law requiring all carceral facilities, jails included, to offer complete addiction treatment. But, we’ll need some money for that.

Addiction treatment in jails

For centuries, detention centers of every kind left inmates with substance use disorder on their own. The approach was hands off. Says Jon Young, commissioner for Camden County, “Hey, go over there, sit on that bed and just sweat it out for 24 to 48 hours and you’ll be good.”

Except that doesn’t work for people addicted to heroin, fentanyl and the like. Symptoms of cold-turkey opioid withdrawal include sweating, chills, shaking, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting. Unassisted withdrawal can also be deadly: Since 2013, four people have died in Bucks County’s jail as a result.

Of those people who are incarcerated who do survive DIY detox — many simply find a way to use while locked up — they are, within two weeks of release, 12.7 times more likely to overdose than the general population, according to the National Library of Medicine. Anyone who’s paid attention to the opioid crisis has heard the story of the kid, cousin, brother, neighbor who got clean, decided to use just one more time, overestimated his tolerance, and O.D.’d.

“We found people weren’t getting sober because of their mental health symptoms. The only way for individuals to be successful is to treat both at the same time.” — Dr. Nikki Johnson

Overdose happens much less frequently after medication assisted treatment (MAT). Since the FDA approved methadone in 1974, MAT has become the “gold standard” in opioid addiction treatment. MAT pairs one of three prescribed, supervised pharmaceuticals, typically methadone, buprenorphine or naltrexone, which prevent cravings and withdrawal symptoms, with counseling and other forms of talk therapy.

MAT is, by far, the most effective treatment for opioid use disorder. Rhode Island became the first state to mandate MAT in all of its prisons in 2016. One year later, they saw a 61 percent drop in post-incarceration overdose deaths.

It’s more common to offer MAT in prisons than jails. The average prison stay is 2.7 years; the average county jail stay is 33 days. Longer stays mean facilities like SCI Chester have more capacity to offer more rehabilitation. Today, 10 state prison systems continue and initiate MAT treatment, including Pennsylvania.

As of 2020, only 120 jails in 32 states — out of more than 3,000 jails nationwide— offer MAT. Here in PA, 16 of 67 county jails allow inmates to continue MAT regimes once incarcerated, and only three counties — Philadelphia, Montgomery and Franklin — allow inmates to initiate treatment. Nine jails offer no treatment at all, and 11 offer MAT to pregnant women only. In 2020, our state’s jail population was 31,790. About 63 percent of those people — 20,027 — had substance use disorder.

Still, the movement to provide people in jails with addiction treatment is growing. Leading the charge: Denver, with a serious assist from Colorado.

Denver’s recovery program

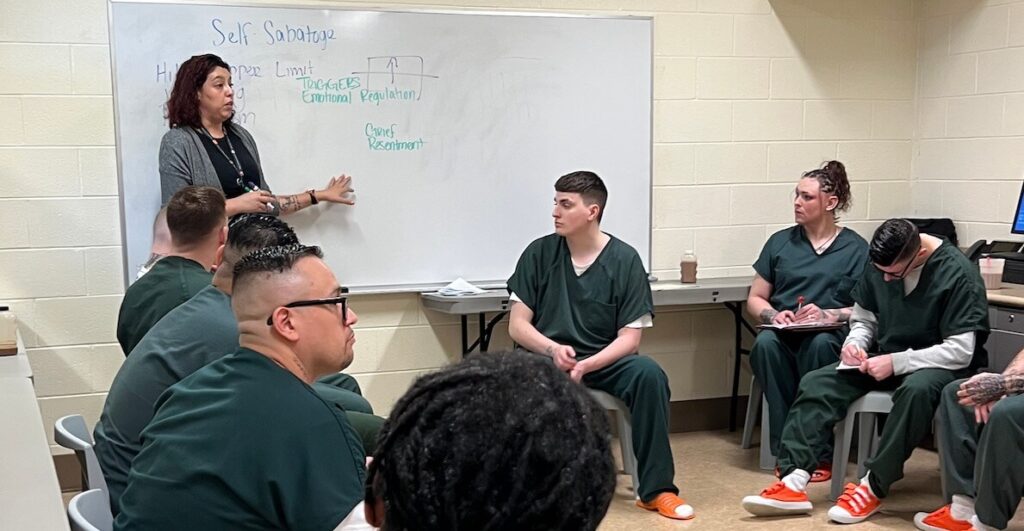

On a recent walkthrough of Denver’s Downtown Detention Center, Sheriff Elias Diggins watched as a small group of incarcerated men sat around a whiteboard and listened to mental health providers speak on addiction treatment and recovery.

The discussion covered depression, anxiety and self-sabotage during the rehabilitation process. The men in attendance shared their struggles and offered each other support and advice. Diggins met one young man, newly sober, whose opioid addiction had kept him apart from his young children for years. “He [said he] looks forward to staying on a sober living path so he can be the dad that they need,” Diggins says.

Diggins was moved. He remembers how his own father’s addiction to alcohol put a strain on his family; he also recalls visiting him in this same jail when he was a boy. “I wish my dad had an opportunity to give the addiction treatment that he needed while he was in custody,” he says. Since launching last year, they’ve started 883 men and women on MAT medications; 578 individuals successfully completed the program.

MAT is most effective when paired with mental health treatment. Dr. Nikki Johnson, chief of mental health services for the Denver Sheriff’s department, says that’s because people often turn to opioids and other drugs to manage symptoms of mental illness.

“When I first started in the field, there was the idea that someone needed to be sober before they could get mental health treatment. What we found during that time period was that people weren’t getting sober because of their mental health symptoms,” she says. “The only way for individuals to be successful is to treat both at the same time.”

The state of Colorado agrees. Last year, they passed the Fentanyl Accountability And Prevention, which requires all carceral facilities in the state to provide people struggling with substance use disorders with both MAT and mental health services.

How to pay for MAT

MAT is expensive. Just one dose of the monthly injection version of Sublocade costs $1,800, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported. Denver spends over one million dollars in grant money per year to run their MAT units. Funding for PDP’s programs comes from a mix of taxes and state-channeled federal funds.

To help more states and counties implement MAT programs in jails, Sen. Cory Booker introduced the Rehabilitation and Recovery During Incarceration Act, which would allow correctional facilities to use Medicaid to pay for mental health and addiction recovery services for the entirety of a person’s prison stay. Right now, the federal government funds these services using Medicaid only for the last 90 days of a sentence — and then only if states apply for a waiver first.

Could this increase taxes? Maybe. On the other hand … We are already paying.

Opioid addiction itself is expensive, not just fueling crime, but also filling hospital emergency departments, destroying families, decimating neighborhoods. According to the CDC, the opioid epidemic cost the U.S. almost $1.5 trillion in 2020 alone. And that’s just dollars. The emotional costs of the crisis — the destruction of loved ones, parents, children, friends, homes — is, quite obviously, incalculable.

A New Jersey testimonial

Sen. Booker announced his legislation at the Camden County Jail, New Jersey’s first jail to offer inmates all three major opioid addiction medications, in concert with counseling services and reentry support. Crystal Quigley opted into the program a year ago after struggling with addiction for years.

She says taking one monthly shot of Suboxone “completely killed the cravings … It made me feel more normal than I had in my entire life.”

Quigley was released on parole in March and lived in a halfway house for several months before moving back home. Today, she’s reconnected with her daughters and talks to them every day. Training to become a peer recovery specialist with Camden’s re-entry support program, she wants to help others struggling with addiction — and, one day, would like to start a reentry recovery house to support other people like her.

When she thinks of her time in treatment, Quigley says, “It’s actually a beautiful program. I don’t know how I would’ve gotten through without it. I don’t have any desire to get high. The only desire I have is to do better.”

MORE FROM THE CITIZEN ON CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFORM