Philadelphia is rightly lauded as the birthplace of American democracy: Jefferson penned the Declaration of Independence here. The framers debated, drafted and signed the Constitution here. But as we celebrate those monumental feats, it’s also important to remember that Philadelphia symbolizes not only the triumphs, but also the trials of American democracy.

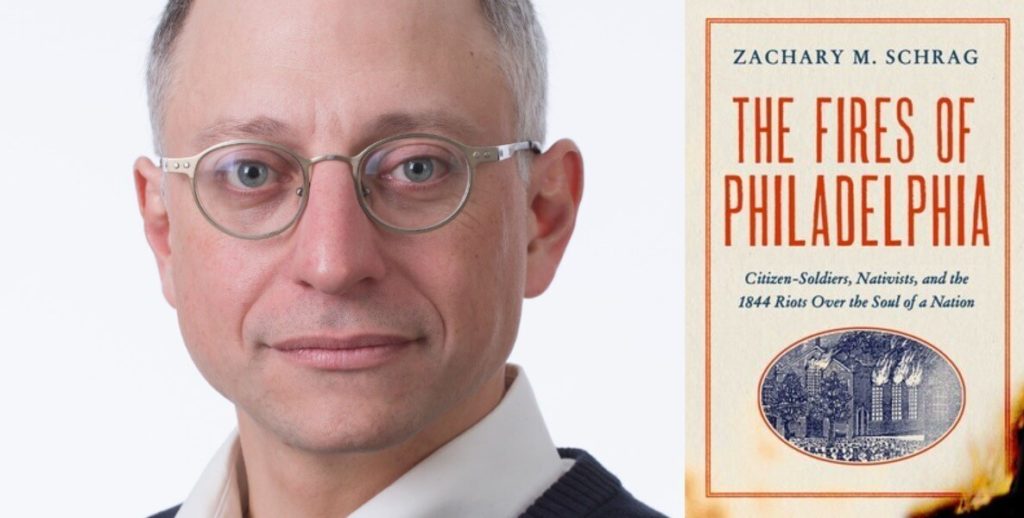

One of the challenges American democracy faces today—and always has—is how to promote toleration and peace across diverse socioeconomic, religious, and racial groups. As Zachary Schrag, a history professor at George Mason University, lays out in his new book, The Fires of Philadelphia: Citizen-Soldiers, Nativists, and the 1844 Riots Over the Soul of a Nation, our city in 1844 laid bare the challenge of maintaining social peace amidst our diversity. White Protestants, referring to themselves as “Native Americans,” attacked Irish Catholics—many of them recent immigrants. Churches were burned; people were shot indiscriminately; democratically enacted law and individual rights were momentarily overtaken by tribal violence.

MORE ON POLICING, PROTESTS & GUN VIOLENCE

Professor Schrag relates the harrowing story of how the city burst into flames in the summer of 1844. During the initial May riot in Kensington, “Native Americans” and Irish Catholics engaged in guerrilla-style warfare in the streets. During the course of the riots, which stretched through July, two churches were burned to the ground and one church—Saint Philip Neri in Southwark—was assaulted by a nativist mob. (They even bombed the church with cannon balls.)

Eventually, a ragtag group of militiamen were able to restore order, if not a genuine peace. In The Fires of Philadelphia, Schrag tells the forgotten story of how Philadelphia’s tribal hatreds exploded into chaotic violence, engulfing parts of the city in literal flames.

Philadelphia—and America—are still not immune to these pressures and tensions today. We still grapple with tribal hatreds of various sorts, and sometimes these tensions bubble up and threaten the rule of law and democracy itself, as evidenced by the tumultuous year of 2020—and the Capitol insurrection on January 6 of this year.

I reached out to Schrag to talk about what the Philadelphia riots of 1844 can teach us about our current debates over American identity, tolerance, policing, and democracy. What follows is an edited and condensed transcript of our conversation.

Thomas Koenig: Thanks so much for joining us, Professor Schrag. I want to begin with a quick two-part question: What’s your book about? And what’s its significance for us today?

Zachary Schrag: The book is a history of a series of riots that took place in Philadelphia in 1844. There was one wave of violence in May of 1844, then a kind of uneasy peace for a few weeks, and then another outbreak of violence in July. And in both cases, these were essentially attacks on the Catholic community, especially the Irish Catholic community, by a rising group of people who called themselves “Native Americans.”

You might think of that term in terms of indigenous Americans, but these were people primarily of Anglo Saxon descent, who were Protestants, who had been born in the United States, and who saw Irish Catholic immigrants as a dangerous menace to the American Republic.

There’s probably never been a golden age of responsible firearm ownership. Just as there’s not been a golden age of policing. These have been problems for a very long time.

I think this speaks to a number of concerns in the 21st century, the main ones being, first of all, immigration where, obviously, that has resurged as a major political issue in the last two years, with people being concerned about both economic competition from new Americans and also cultural competition in terms of new religions and languages. And then the second major question that became all the more pressing in 2020 and 2021 is that of mob violence, and the appropriate response to crowds, and protesters and mobs. Those are three different terms that kind of bleed into each other. But how do we want our forces of order to respond when there is a big crowd in the streets demanding some kind of political action?

TK: Right. So the first riot in May 1844 starts out as a political rally in Irish Catholic Kensington by the “Native Americans,” and soon enough, it devolves into a riot, into violence. We saw a similar thing happen this past summer when peaceful protests turned violent in some places.

ZS: That’s right. We see this across places and periods. Once you have people in the street, whether it’s a kind of organized group, like a political rally, or parade or protest march or spontaneous gathering, it can very quickly turn into something more violent. And part of that is that crowds are made of lots of people who have different ideas and agendas. So you can have a crowd with 1,000 people who are there to be peaceful and orderly. And you’re going to have 20 teenagers who are not, and yet those 20 teenagers, once they’ve started throwing rocks and bricks and bottles, especially at the police or whoever’s there, can very easily turn the whole scene into chaos.

And it’s very hard for the police to respond to that. Because, you know, again, these 20 teenagers may be surrounded by 1,000 people, you can’t arrest them all. So what do you do? Do you fire at the crowd? Do you try to disperse it? It’s very challenging for any kind of police force that is trying to minimize injury while also protecting order and property.

And then the other factor beyond the sort of unpredictable composition of a crowd is that a kind of surprise event can very often turn things violent. If you read accounts of riots, often a broken window, for example, seems to have a certain psychological effect. Spike Lee captures this in “Do the Right Thing” where that trashcan through the window of Sal’s Pizzeria turns this protest into a riot. And we saw this in Baltimore, for example, with the Freddie Gray riots, that broken window, or a broken bottle can do it.

In Philadelphia in May of 1844, it was a sudden rainstorm that disrupted this political rally and what had been a somewhat predictable, scripted protest, or heckling, turns kind of unpredictable and chaotic when that rain starts to fall, and everyone is running in new directions, and they find themselves in a different setting. So little things like that can turn a crowd violent.

TK: One of my main takeaways from the book was how disorganized and ragtag policing was—or at least the Philadelphia police force was—at the time. Ultimately the militia had to do most of the crowd control. In the aftermath of the violence, were there police reforms that brought forth some forms of modernization that inch us closer to the police as we know it today?

ZS: So the old Anglo Saxon tradition was to put policing in the hands of the community. You would have a sheriff and if he needed some help keeping things under control, he could summon a posse just like you’ve seen in the old western movies. There were posses in cities as well. And sometimes they worked—sometimes you could actually get people to come out and try to overwhelm whatever disorganization is going on whether there’s a crime or riot, a bunch of men of good faith would show up and help the sheriff. And that begins to break down as cities get larger, more anonymous, there’s more crime in the streets, and fewer men willing to risk their lives to help the sheriff.

Most of the violence of 1844 takes place in what were then independent districts [within Philadelphia]. And these districts had almost no police forces. They had a few constables. And then they had night watchmen who would light the lamps and rattle their rattles to call the hour, but were really no match for a determined mob.

TK: Obviously, we need a more modern police force than the posse being called up, but are there elements from that older model of community-based policing that you think could be revived today Philadelphia?

ZS: So this is a question I have for the people who are calling for defunding or abolishing the police, and for some of my fellow historians who have talked about alternatives. The concept of “community policing”, or at least the term “community policing”, shows up a lot. But I’m not really sure what that means in many cases.

You do have to be careful what you wish for because in some cases, a responsive police force is one that responds to the majority and is not ready to defend religious or ethnic minorities like the Irish Catholics or obviously racial minorities either—and you know this is going on in Philadelphia in the 1840s, as well. There were attacks on the African American community. And so one of the reasons that people think a professional police force would be more effective is that it would be neutral in terms of who it protected and served.

But this didn’t work. As soon as Philadelphia does establish a more professional police force in the 1850s, it almost immediately becomes a football between those who want it to be composed of native-born Americans and those who are willing to recruit—guess who?— the Irish. So the idea of the Irish cop comes out of this period where politicians in New York and Philadelphia and elsewhere see this new police force as a great way to get more Irish Americans onto the government payroll, and therefore more Irish American votes at the ballot box.

TK: You recount an immense amount of gun violence during the 1844 riots in your book. Today, when we have spikes in gun violence, inevitably we’re going to have a debate about gun control. Was there any discussion of gun reform in the aftermath of the 1844 riots?

ZS: So the only debate about gun control that I really saw was about trying to keep guns out of the hands of specific groups. Whatever you say about the second amendment to the U.S. Constitution, no one cared about that in 1844; people cared about the Pennsylvania State Constitution, and that had a broader right to bear arms than the U.S. Constitution did. And you could arguably create your own militia company without too much paperwork either. Philadelphia was a pretty well armed town.

In addition to the deliberate violence, people are shooting family members by accident a lot, as they still do today. And then you also have some drunken brawls. Just all kinds of mayhem, which I think reminds us that there’s probably never been a golden age of responsible firearm ownership. Just as there’s not been a golden age of policing. These have been problems for a very long time.

TK: To build off of that, your book really indicates there’s also never been a golden age of municipal governance writ large, at least in Philadelphia. You talk about fire companies in the book. What happened there?

ZS: At the root of the problem—and again, this spans different places and times—is that adolescent boys can be really awful. In Philadelphia, in the 1840s, a lot of these young men end up associated with the volunteer fire companies that start out saying, “we’re going to fight fires,” but they soon become a kind of set of rival gangs who are rushing to get to the first fireplug. And if they’re second to the fireplug, well, they can at least cut the hose of the first company that got there and have the honor of fighting the fire. And if there’s no fire, well, maybe they can still raid the other company and steal its fire engine and smash it in the streets. And this just becomes a perpetual problem. And it’s not every city, but it is several cities, Philadelphia and Baltimore are among the worst.

As a historian, I often cop out by saying, I’m just telling the story and letting others figure out what to do with it. But it was obviously very troubling for me to see what’s happening, not just in 2020, but in the years leading up to it, as we fall into a lot of discord. There are no easy answers.

And so, professionalizing the firefighters turns out to be as important as professionalizing the police in terms of creating some kind of order. And that takes a very long time. One of my favorite letters from Bishop Frances Patrick Kenrick, the Archbishop of Philadelphia at the time of the 1844 riots, is he’s writing to someone and he says, “Oh, yeah, we had another little riot last weekend. But don’t worry it was just the firemen.” You know, because that’s normal!

TK: Yeah, that’s just par for the course! I want to contrast the riots of 1844 with what happened in Philly in 2020. The summer of 2020 in Philadelphia was a violent, tumultuous summer for the city. But there was not a ton of inter-group, inter-tribal violence, like in 1844. Most of the politically charged violence that did take place was between citizens and police. Which is more dangerous to democracy? When you have the citizen and the state (i.e., the police) fighting like in 2020, or when you have like in 1844 two groups of citizens fighting one another?

ZS: That’s a really interesting distinction to make. So you’re right that for the 19th century and into the 20th we have a lot of intergroup violence. This year, people are talking about the centennial of the Tulsa massacre that, you know, was largely non-governmental white people raiding the black neighborhoods of Tulsa, a pogrom which was one of a large series from the 1910s and into the 1920s surrounding World War I.

And as historians have noted, by the 1960s, especially, that has changed where in what we call the race riots of the 1960s, there are many more citizens against forces of order, whether they were Police or National Guard or U.S. Army troops. These days, yes, if you do have people who are right wingers and left wingers in the same place, there might often be a line of police between them. And it is always a question of which way are the police facing and which way are the shields? But I don’t know that we’ve had that same kind of multi-day brawl between rival civilian groups. So that is one thing that professionalization of the police has gotten us. But as you say, having the different groups take turns attacking the police, whether it’s in 2020, or the assault on the Capitol in 2021, is still pretty dismaying for people who hope democracy is a more peaceful and deliberative process.

TK: Speaking of democracy, I want to close with the final lines of your book: “If nothing else, the riots reminded Americans that all deliberative politics and law ultimately depend on the control of violence. Democracy walks a narrow path between military oppression and mob rule.” Is there a call to action for readers, when we reflect on how we can ensure that our city and our nation stays on this narrow, democratic path?

ZS: You know, as a historian, I often cop out by saying, I’m just telling the story and letting others figure out what to do with it. But it was obviously very troubling for me to see what’s happening, not just in 2020, but in the years leading up to it, as we fall into a lot of discord. And in the summer of 2020, especially, when there was a wave of civil unrest that we’ve not seen since the 1970s. And so, there are no easy answers.

In part, I found myself in an odd position of kind of rooting for the militia, especially during the riot of July of 1844. They are risking their lives to defend a Catholic Church, some of them are Catholic, most of them are not, some of them are actually anti-Catholic, but they still put duty ahead of their own personal beliefs. And I do think a democracy needs that. Alexis de Tocqueville in “Democracy in America” writes about the tyranny of majority in terrifying terms, and he actually references an 1812 riot in Baltimore, where the militia just wouldn’t show up to defend people they disagreed with. And that’s a terrible thing.

That said, it’s very clear from what we’ve seen, from the George Floyd protests and the recent history of policing that too much policing is a dangerous thing. So when the Nativists complain about military rule, when they warn about the possibilities that the militia would unjustly block their speech and put newspaper editors under risk of imprisonment, you can’t dismiss that entirely, either.

And so this is where I came up with that idea of the rather narrow path that we are walking, that, you know, leaving everything to the police or abolishing the police are both very dangerous.

TK: Thank you, Professor Schrag.

ZS: Thank you. It’s a pleasure.