Sophie Heng is about three weeks away from opening night of Theater of Witness’s Walk in My Shoes. She’s standing in the middle of a large, sparsely furnished room in front of her fellow cast members on the second floor of the Philadelphia Ethical Society. It’s a Thursday evening rehearsal and Heng, clasping her hands in front of her, begins speaking.

“‘Mom, I’m going to the store and I’ll be right back,’” Heng says in a tight, controlled voice, recalling an evening in April, 2016. “Those were the last words that I heard from my 19-year-old son Phillip. When he didn’t return, I knew something had happened, but I didn’t want to believe my thoughts, but a mother always knows. When he walked out the door, it was so ordinary that I didn’t even look up. And then he was gone.”

Be Part of the Solution

Become a Citizen member.Heng, born in Cambodia and now in her 30s, goes on to recount the anger she felt towards the Philadelphia Police in the subsequent investigation into Phillip’s death. She delivers this speech, a mixture of bravery, pain, sorrow, love and frustration, with remarkable composure for such fresh emotional wounds. After she’s finished her run-through, Hakim Ali takes the center of the room. He is now in his 70s and in a rich deep voice tells a story dating back to 1909, when his father’s cousin was lynched and castrated in Georgia.

“Now, you can’t hear a story like that without feeling some anger, some kind of rage,” says Ali, an ex-con who served 40 years. “That was the rage I felt that sent me down my own road of destruction. Now, I have my own story to tell.”

It’s easy to forget that Heng and Ali (part of a seven-member cast) are not professional actors. The monologues are beautifully written and delivered. This level of authenticity, conviction and immediacy are what trained actors aspire to. But, these cast members are tapping into actual memories and emotions.

Walk in My Shoes, which premieres November 10-11 at the Painted Bride, uses citizen cast members and police officers to explores the relationship between the police and the public and the fear, mistrust and anger that can exist between them. The hour-long show (no intermission) presents stories that explore injustice, racism, poverty, and suffering from the perspective of four Philadelphia police officers and three members of the community.

“We’re talking about things that happened in our lives,” explains Ali about the content in Walk in My Shoes. “It’s not like I’m just reading lines from a book. I’m saying things about my life and how I was affected by what I’d done. These stories need to be told and hopefully there’s some sort of effect. Sometimes people need to hear horrible things and then see they don’t have to stay that way. That, more than anything, is why I do this.”

Walk in My Shoes is the most recent project by Theater of Witness founder Teya Sepinuck. Sepinuck, a trained dancer and counselor, has used this method to create works for the past 30 years—“to find the medicine in the stories of suffering.” She’s mounted productions in Northern Ireland about “The Troubles” there; in Poland, about runaway girls and about men serving sentences at the Bemowo prison. In Philadelphia, 2005’s Beyond the Walls, about people affected by inner city violence, toured prisons, community centers, schools and faith organizations for two years, then-State Sen. Dwight Evans included the piece in his Blueprint for a Safer Philadelphia.

“One way to make a difference,” says Sepinuck, who writes each person’s parts based on extensive interviews with them, “is by knowing each other’s stories—the pain and the issues—and from being human together. It’s so hard to get past the rhetoric and extreme divisiveness, but when you do, there’s a lot of beauty.”

“It’s never too late to change,” says Ali. “Until we have this perfect society, I don’t think you’ll ever get rid of the trauma we experience, but we learn how to control it or how to use it in a more productive way. Your enemy doesn’t have to stay your enemy.”

Sepinuck may not possess obvious attributes for the task of examining race, disenfranchisement and community-police relations; she’s not a person of color, nor has she experienced trauma from the police or from someone in the community. But she does have the expertise, sensitivity, and gift for building respect and trust with and between her participants.

“I’ve spent my life trying to run away from superficiality,” says Sepinuck. “I grew up in a very comfortable, upper-middle class suburban home where the talk was about nothing real. My mom’s friends played cards and went shopping. I was hungry for what’s real. I wanted to know where were the deep stories, the stories of justice. So, I’m not attracted to trauma, but attracted to the journeys we take as humans.”

Sepinuck faced a significant challenge in finding and persuading police officers to join in this project that dredges up issues of police misconduct. Fortunately, Sepinuck had someone in mind to co-produce the project and who could also get police buy-in: Philadelphia Police Inspector Altovise Love-Craighead. “There isn’t a more perfect person for this,” says Sepinuck.

The two women knew each other from Behind the Walls, where Love-Craighead recounted the story of her brother’s murder in 1997. With Love-Craighead vouching for the project, police officers volunteered to attend the listening circles that Sepinuck uses to begin each project and gather stories.

“Technically, we don’t need permission to participate,” says Love-Craighead of her fellow police officers because it’s unpaid volunteer work, “But, because of the sensitive nature of the topic, I thought it best to get approval from the department. I spoke to Commissioner Ross and he really wanted me to pursue it and see it through.”

At the listening circles Sepinuck typically holds to begin her projects, she takes copious notes and then selects the stories that best fit together—and which people are ready to tell them publicly. Not all selected participants make it to the final performance. Some stories are still too raw and some people are still too much in the middle of their trauma to be so vulnerable on stage. Yet, other participants immediately stand out at the listening circles.

“If I’m getting chills and I feel I can’t breathe,” explains Sepinuck, “then I know they’re the right person. Koz [police officer William Kozlowski] was really open and willing to jump in and go deep without knowing everybody in the room. He wasn’t afraid to be vulnerable and was really excited to be there.”

Is Kozlowski nervous about getting up onstage? “Nervous? Absolutely,” says the young officer and former soldier in Iraq with a smile. “Scared? Not really. I’m more nervous about letting down the group than actually being up on stage. I love this project because, like Hakim was saying, these stories need to be told. I’m a geek, and one of my favorite things is Star Trek. I love it not only because it’s cool, but I love how everybody could live and work together despite being different races, religions, gender, for a common good, a better good. I just hope for a better future out of this.”

“In the beginning,” says Love-Craighead, “I heard stories about police officers that made me cringe, but we need to hear the stories. If we don’t hear that, we can’t make the change we need. They allow us to grow together.”

Love-Craighead says she too hopes the show will reveal a human side to cops that the public might not always see. “We become hardened to tragedy in an effort to survive and remain professional day in and day out,” she says. “But the side of us people don’t see is our humanness and when we start to be affected by our work. They see us at the scene, but they don’t see us at home and how we’re impacted. The production will allow them to see we’re humans and we try to find ways to deal with our feelings. Police officers have a boatload of issues with domestic violence, alcoholism and suicide.”

Work on the production has allowed conflicting sides to be in the same safe space and listen to things that may be hard to hear. For the police, it is similar to a de-escalation technique of ventilating stories by allowing an aggrieved person to speak freely and have their pain acknowledged. It restores dignity when someone is allowed to express their outrage and be heard. “In the beginning,” says Love-Craighead, “I heard stories about police officers that made me cringe, but we need to hear the stories. If we don’t hear that, we can’t make the change we need. They allow us to grow together.”

In the Thursday rehearsal, some of the cast members are sitting in chairs in a circle talking about what they want out of Walk in My Shoes. The issue of troubled police-community relations is not going away, a growing list of dead African-American males killed by police officers is continuously in the news: Michael Brown, Freddie Gray, Eric Garner, Philando Castile, and this past summer in Philadelphia, David Jones.

This play is not going to change all that, for everyone. But Sepinuck says every production has proven cathartic in some way. She has seen participants—previously “enemies”—make lasting relationships. Some participants have started new careers after feeling empowered, including going into the ministry. “I can’t tell you how many people have reported a deep healing,” says Sepinuck. She has heard of audience members who have forgiven significant people, taken up social causes and become more active in working for social justice. “And many have reported that their eyes and hearts have become open,” adds Sepinuck. “There are many ripple effects.”

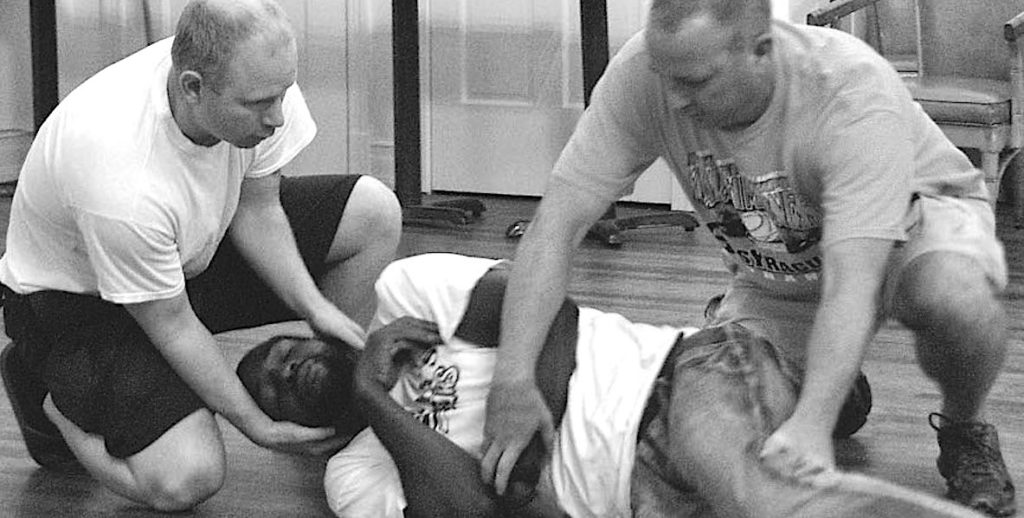

Heng’s words recall a story that Sepinuck shared about one of the group’s first rehearsal exercises when Ali, whose own story includes being savagely beaten by Philly cops in West Philadelphia at age 15, collapsed on Kozlowski, who held and rocked him. Sepinuck recalls, “I knew the back story and to see Hakim cradled by a police officer and making himself vulnerable. I got how huge that was.”

“It’s never too late to change,” says Ali. “Until we have this perfect society, I don’t think you’ll ever get rid of the trauma we experience, but we learn how to control it or how to use it in a more productive way. Your enemy doesn’t have to stay your enemy.”

Walk in My Shoes, November 10-11, Painted Bride Art Center, 230 Vine Street, tickets: 215-925-9914, paintedbride.org and theaterofwitness.org

Correction: A previous version of this story misstated Altovise Love-Craighead’s position. She is a police inspector.