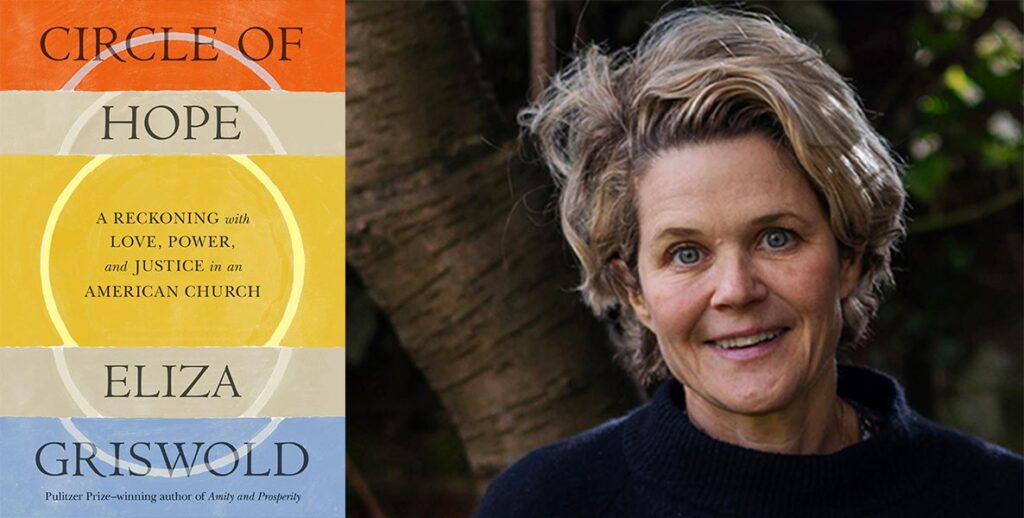

When author and New Yorker magazine writer Eliza Griswold first started reporting her new book, Circle of Hope: A Reckoning with Love, Power, and Justice in an American Church, she thought it would be a look at an American subculture of “happy, devoted young people living and working as Jesus did in unconventional ways.” At the time, Circle of Hope was just that: A progressive, social justice and service-oriented church with four pastors operating three branches in Philly and one in Camden, doing work they believed was righteous and truly Christian.

That did not last. Over the three years of reporting Circle of Hope —spanning the pandemic, and the racial reckoning following the murder of George Floyd — what Griswold witnessed was the church’s unraveling. Her book, which the Citizen is launching with a party and book signing on August 12, chronicles that journey. But the lessons it imparts — about community, social justice, American society and the ways in which we come to terms with history and progress — are relevant well beyond the confines of Christianity.

“What happened with Circle of Hope is the same that happened in so many traditionally liberal spaces after George Floyd, whether they dealt with saving birds, nature conservation, women’s rights,” Griswold says.

Griswold, a Philly native who has also done terrific reporting on Pennsylvania politics, will talk about her book at a Citizen event on August 12 at Fitler Club. The event will include a cocktail hour and book signing.

I caught up with Griswold a couple weeks ago while she was reporting about the election in Philadelphia to talk about her book and its lessons for communities well beyond the church.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Roxanne Patel Shepelavy: How did you first come upon Circle of Hope?

Eliza Griswold: In Philadelphia, there’s an intentional [Christian] community called The Simple Way in Kensington. One day I was watching the man who founded it, Shane Claiborne, melting guns into garden implements at a mobile forge on a street there, living out the biblical injunction “swords into plowshares.” As he was pushing the barrel of an AK-47 into the forge, I saw behind him people who were clearly in a church: They were heavily tattooed, in button-down thrift store chic, with trimmed beards. They looked like Anabaptists — which they were.

I asked Shane who they were and he told me about Circle of Hope. Circle of Hope were people who have given their lives to living the teachings of Jesus, living literally the Sermon on the Mount, which is Jesus’ greatest moral teaching. They gave themselves to that, set themselves apart as authentically doing that together. They were committed to one another as profoundly as married people are. This was their chosen family.

What happened with Circle of Hope is the same that happened in so many traditionally liberal spaces after George Floyd, whether they dealt with saving birds, nature conservation, women’s rights.

By this time, I was tired already of the White Christian Nationalist evangelical narrative. [Editor’s note: Griswold wrote a must read New Yorker story about Pennsylvania’s Christian Nationalist gubernatorial candidate Doug Mastriano in 2021.] I knew there were people standing up to these conservative narratives in a very Christian congregation. I wanted to immerse myself in a congregation like that.

I thought it would be a funny, tender book about a subculture at the edges of evangelicalism. That is not what happened at all.

Did what happened make for a better story?

That made it way more interesting, way more authentic. It became about a reckoning that every institution in America was facing over the last few years. It became a universal story about community and values, instead of a simple story about religion.

You started reporting in 2020, and then the pandemic happened. That’s when cracks started to emerge?

Yes. Living the virtual life affected every community, especially those that put a premium on togetherness, like the church. They saw themselves as being one church, in four different locations. They were hyper-local before local was cool: They saw themselves as of the community they were in. Showing up in person was essential

Going online showed the cracks. First of all, not everyone agreed with being online. Some said,

“Are you listening to the governor or listening to Jesus? We can go to Home Depot, but not to church?” By design, the church has never had high production values — it’s anti-slick. So from a pure engagement level online, that didn’t work.

And it forced the four very different leaders to lead together, which was fraught from the start.

In what way?

It revealed difficult gender dynamics. [The pastors included two men and two women.] The men took off with it and riffed on scripture in a very evangelical way. The women remained silent. They felt they had to be aggressive to break in when the men were talking and that wasn’t the way in which their church worked. Women can’t be pastors in conservative evangelical spaces, and the fact that they had women pastors seemed very progressive to them. But this showed they hadn’t solved the gender dynamics at all.

And then George Floyd was murdered by a police officer in Minneapolis.

Yes, and what happened in the George Floyd aftermath, as in so many traditionally liberal spaces, was a tension that was often generational of, We can’t do the work of saving the world if we don’t look within. And in many cases that led to upheaval.

For the older generation, the internal reckoning was a waste of time: Why are we interrogating our past if people are in great need now? That’s a valid argument.

The younger generation said: That’s White saviorism, and we have to look inward at ourselves. That’s also a valid argument.

The people who started the church, who were from Southern California and were influenced by the Jesus freak movement, were accused of being part of White supremacy culture. They didn’t respond very well to that, and got very defensive. And that was seen as a symptom of that White culture. The criticism, and their reaction, drove a wedge between them and the church they created. That forced them out in a way that felt like they were being excommunicated.

What do you mean?

They were told they couldn’t lead at the church, and they saw that as being banned from the church. Circle of Hope is part of Anabaptism, a religious tradition that dates back to the 1600s in Philly. They are a sect that’s been baptizing people in the Wissahickon for 300 years.

This idea of Christians who are radical and skeptical of the government and who live their principles authentically, that were about abolition and social justice — like Quakers and Anabaptists — comes out of the radical Reformation. Both Anabaptists and Quakers have the idea of a ban: If you stepped out of the norms upheld by a community, you would be subject to being excommunicated. It was the original cancel culture.

What divides this church is the same as the polarization of America: You have to be right or you’re totally wrong. We see the cost of that kind of thinking — it’s dangerous because answers to those questions will always be changing.

That idea is very subjective now. The idea of punishing people for different shades of belief becomes really problematic. One of the pastors [Jonny Rashid, the only pastor of color] wrote a blog post in defense of cancel culture, basically saying that if your beliefs are reprehensible then our society should punish you. He was accused of waging a coup against the founding family and interrogating their past against these new norms of culture and finding them in violation, and using that as evidence that they could no longer lead the church, which resulted in their departure.

And that eventually led to the church itself breaking up?

They were driven out, and then the church had to face another longstanding problem, which had to do with LGBTQ policy. Like every other institution or community that’s rooted in some kind of moral value, they had to revisit what they once held to be true, about race, gender and sexuality. The sexuality one was so big because their Anabaptist denomination [which vehemently opposed same-sex marriage and LGBTQ pastors] owned their buildings, and all the assets of the church. If they were going to affirm queer members and queer pastors, they would have to give up all their worldly treasures. They ultimately did.

Three congregations still exist, and are trying to reset. They would say that churches are not about a building, they’re about people. But you need a place to gather.

You mentioned that this book is about more than just this church. In what way?

I’m not a church person. I’m not sure I would pick up this book unless I knew it would apply to me. This goes beyond that. It’s every organization from the Audubon Society to Times Up that is being forced to answer these questions about how to be a community, and how people can hold different understandings of values and not fall into conversations about absolute right and absolute wrong. What divides this church is the same as the polarization of America: You have to be right or you’re totally wrong. We see the cost of that kind of thinking — it’s dangerous because answers to those questions will always be changing.

Isn’t that what religions are? A set of “right” beliefs versus other “wrong” ones?

This wasn’t because of religion. Any ideology is dangerous in its uniform view of what its values are. Their exceptionalism is the problem, their sense of themselves as different. We throw out the term American Exceptionalism a lot, and it’s often used as a criticism of conservative values. But it’s just as corrosive in progressive contexts as conservative.

You say you’re “not a church person.” But you were raised as a church person, right?

My Dad was a big muckety muck in the Episcopal Church, with robes and crosses and hats. [Editor’s note: Frank T. Griswold III was presiding bishop of the 2.5 million-member Episcopal Church from 1996 to 2005.] But the truth is he was doing yoga on a sheepskin rug everyday and was really a mystic. Seeking in our house could mean a lot of things, and he was open to that.

I didn’t understand until 9/11 about evangelicalism. I never grew up in any form of Christianity that thought it was better than anything else. My dad always said that he was a Christian because that was the faith he was raised in. He understood the sociological aspects of why he was an Episcopalian, and that you can’t take context out of why people believe what they do. He had a humility and a humor that is not at all possible among fundamentalists. He was very skeptical of any religion that believes it has the answer and others don’t. Through my dad, I had a front seat to the culture wars. He consecrated the Episcopal Church’s first gay bishop, which led to a modern day schism.

I see myself as a translator when I’m reporting inside a church. Where the mainstream media gets Christianity wrong today is that we imagine people are becoming more secular because they’re leaving their churches. They’re not: They’re seeking other ways to follow God, more authentically in their practice.

Circle of Hope book launch party, Tuesday August 12, 5 pm-730 pm, Fitler Club Ballroom, 1 South 24th Street, $5 for entry, $30 for entry + book. RSVP here.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated how many Circle of Hope congregations still exist in some form. It is three.