It was never about the coffee. Not really. Nick Bayer, founder and CEO of Saxbys—the Philly-based coffee brand with 25 cafés in Philly and beyond—will you tell you that himself.

He’ll tell you quite a lot, actually: Bayer is something of an open book when it comes to his business and life philosophies, his background, his vision, his failures, his game plan going forward. If you know Bayer, or if you are at all acquainted with his story, then you know that he’s a guy from reasonably humble beginnings who was born to young, hard-working parents in Chicago, who benefited from a few teachers who believed in him, and who eventually landed at Cornell University, to the delight of his parents, who hadn’t enjoyed the advantage of a college education.

It wasn’t long into his university experience that he’d realized a couple things. First, life had shown him clearly just how closely opportunity is linked to education and to having people in life who invest in you—and he’d realized, too, how access to both of those advantages are often simply an accident of birth and circumstance. Second? It was there at Cornell that he was first exposed to the world of business, and not just that, but “the power there, both the good ways and the bad ways that business can affect the world.”

“Inequality is growing,” Bayer says. “If businesses don’t change, the inequality is going to get worse. If good businesses don’t step up as force multipliers, we’re going to go backwards.”

It’s not hard to see now where these dual epiphanies would eventually lead Bayer, but this was the late ’90s, long before anyone was talking about “social entrepreneurs,” before the concept of double impact had taken off as a business model, even before schools were teaching entrepreneurship in any meaningful way. Even so, Bayer says, “that’s where my heart was.”

At that point, he knew he wanted to operate a business, and he knew he wanted to use that business to positively impact peoples’ lives. As he tells it, he chose coffee largely because “there’s no barrier to entry, and it’s the perfect business to serve anyone, and to employ anyone.”

He launched Saxbys in 2005, and then spent the next decade or so in a state of evolution: There were franchises, then a recession, then a reorganization, and, eventually, a revelation that the path to success—and the realization of his dreams to make a real impact—was about building a company around a mission and selling coffee as a means to that end, rather than the reverse.

RELATED FROM THE CITIZEN

In an industry known for high levels of burnout, local ad agency Truth & Consequences has a different blueprint for success: taking care—great care—of its employees

Since then? Saxbys has become the quintessential social-impact business. For one thing, Bayer has launched a remarkable and robust workforce training program with the goal of democratizing education and opportunity. That’s played out in part via 12 “experiential learning cafes” currently situated on eight different college campuses (with more coming soon). And in the meantime, until Covid crippled us all, business was on a steady upwards trajectory, profitable and growing.

“The week prior to the lockdown, our comp sales were up 12 percent across all of our cafes,” Bayer says. And then the world shut down, and so did his cafés—from March of 2020 until August.

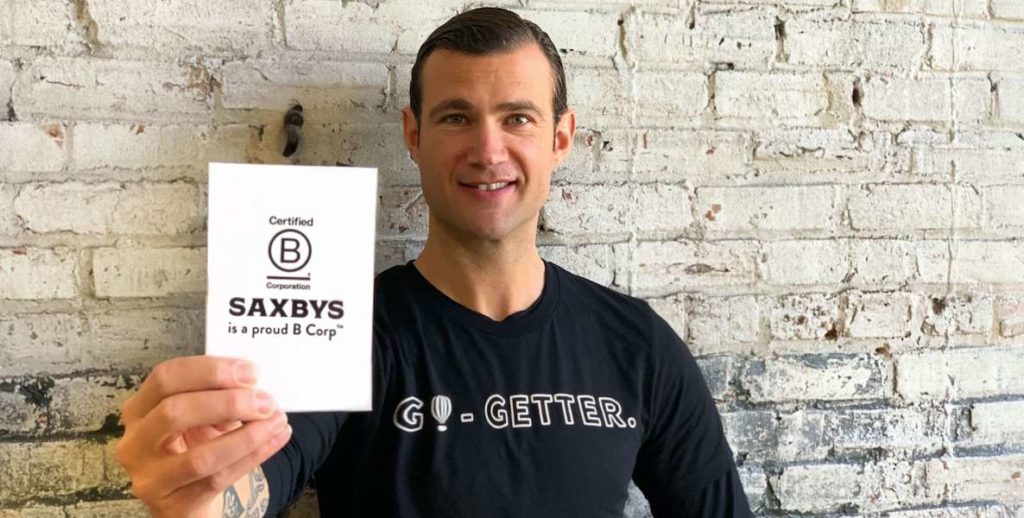

But there was an upside here: Slower business meant that Bayer and his team had time to gather, organize and document the various positive impacts they’ve spent years cultivating, records that allowed them to formally apply to be certified as a B Corporation. As of this month, that’s what Saxbys finally is—a B Corp, one of nearly 4,000 in the world, 61 in the state, and just 24 in Philadelphia.

More than just good marketing

It’s not an easy process, working for a certification from B Lab, which is the now-famous brainchild of another Philadelphian, Jay Coen Gilbert. Since Gilbert co-founded the nonprofit in 2006 as a way to hold companies accountable for their impact in the world, the organization has garnered the esteem of leaders around the globe. To be certified as a B Corp (the “B” stands for “benefit”) requires a for-profit business to go through an independent and deeply rigorous audit that scores the company’s impact on its workers, its suppliers, its community, the environment and its customers.

The B Corp status—exemplified by social- and environmental-impact giants like Ben & Jerry’s, Patagonia, Allbirds—is increasingly desirable and more prevalent these days, as more companies are shifting attention and loyalty from shareholders to stakeholders.

“Companies—big companies in particular—are really good at talking,” Bayer says. “Anyone can say they’re impactful. All it takes to label yourself as an impactful business is a good copywriter and microphone.”

In other words, the business world seems to be coming around to the idea of double impact, this notion that it’s both responsible and beneficial to business to not just exist to make money for a tiny group of people. Instead, the goal is to work for the more sustainable benefits of serving increasingly values-driven customers, the wider community, workers, and the supply chain … all in addition to the shareholders. It’s a trend that Gilbert’s B Lab Global co-founder Andrew Kassoy has cited as a driver of B Corp growth; it’s also a model that drives Bayer.

Nevertheless, I say to Bayer, isn’t a B Corp certification a whole lot of work just to get a stamp of approval for something you’re already doing? What’s the point of this, exactly?

“I think it’s about the importance of walking the talk,” he says. “Companies—big companies in particular—are really good at talking. You hear the term ‘greenwashing’ sometimes, right? It’s easy to do. Anyone can say they’re impactful. All it takes to label yourself as an impactful business is a good copywriter and microphone.”

What B Corp brings, he says, is proof of impact, and verification for the world that a business is making choices with positive rather than negative effects. You can’t buy your way into certification; you can’t talk your way in; you can’t hire a consulting firm to give you a B Corp glow-up and market your way in. The impact assessment process literally proves that you’re doing some good in the world. In this way, he says, it’s also a blueprint for the business itself. “We had to make iterative, impactful changes for years to get to this point.”

“We want to break the ceiling.”

In terms of impact, what Saxbys is probably most celebrated for is the Experiential Learning Platform (ELP), which is all about Bayer’s passion: Creating a pathway to education and opportunity for anyone who wants it. He’d been hearing the same message over and over from professors at schools where he’d visit as a speaker—and Nick Bayer, an entrepreneur in residence at Cornell and board member of the School of Entrepreneurship at Drexel, is constantly visiting schools to speak to students; the day before I spoke to him, he had been to four different campuses in one day.

Anyway, he’d been hearing from those professors that what was missing in the world was more opportunities for students to have experiential entrepreneurial education to balance out their classroom learning. It struck him as a problem he could address.

RELATED FROM THE CITIZEN

Camden-based Hopeworks is expanding its job training and placement mission with an eye to fighting regional poverty, hundreds of jobs at a time

Bayer’s ELP debuted in 2015, when he talked Drexel University President John Fry into letting him open a Saxbys on Drexel’s campus as an “experiential learning cafe.” It seemed at the time like a perfect fit, Bayer says. His company was mission-driven (the mission: “Make life better”) at a time when young people were becoming increasingly attracted to mission-driven business. “They’re also attracted to cafés,” Bayer points out: The best-performing cafés are often found around college campuses. And, he realized, “our cafés are so busy that there’s all these moving parts of business involved in daily operations”—HR, finance, hiring and firing, ordering, guest service, profit and loss analysis. “It all happens every day at Saxbys.” Meaning his cafés would be the perfect place to help people learn all sorts of skills that come into play in any business, anywhere.

That café, which was designed and run wholly by students, did indeed prove to offer priceless experience for those students, who learned the ins and outs of the business, and were also trained in inclusivity, emotional intelligence, financial management, leadership skills, critical thinking, “cultural agility,” and guest service.

Also? The place was profitable. And lo, a model was born. Now, six years on, Bayer’s ELP has cafés on eight campuses including Temple, Penn State, St. Joe’s, Georgetown, and, most recently, Bowie State in Maryland, Saxbys first outpost at an HBCU.

This is a generation that may have watched their parents lose jobs in 2009. They’ve seen companies get rich while people who work for them stay poor. They’ve seen Donald Trump, the “businessman,” behaving the way Donald Trump behaves. “Young people don’t see a lot of instances as to why businesses are good,” Bayer says. “They automatically think they’re bad.”

Student CEOs (SCEOs) run the whole café, Bayer says: They take a semester off (for credit) and get paid to literally run a business that serves 1,000 guests a day for six months at a time. The SCEOs get coaching and counseling; they get real-life managerial experience; and they get a hell of a resume-builder. “They get jobs immediately in all different industries,” Bayer says. To date, Saxbys has employed 68 SCEOs.

Meantime, there’s something else at play here, and it’s bigger than just job training. In his many visits to college campuses, Bayer says, he’s noticed that “so many kids today think of business as evil.” He gets it: After all, this is a generation that may have watched their parents lose jobs in 2009 after the recession. They’ve seen companies get rich while people who work for them stay poor. They’ve seen Donald Trump, the “businessman,” behaving the way Donald Trump behaves. “Young people don’t see a lot of instances as to why businesses are good,” Bayer says. “They automatically think they’re bad.”

So what happens, then, when there’s a B Corp devoted to making positive change embedded right there in the middle of campus? It’s not just lip service: The SCEOs are even empowered, Bayer says, to grant community requests for various partnerships and philanthropy. Bayer hopes that Saxbys’ mission-driven ethos might be proof positive for students that not all businesses are bad. That “in fact, business can be a huge force for good, and make the world a better place, a more equal place, a more just place.”

RELATED FROM THE CITIZEN

Local product design company Oat Foundry tackles awesomely out-there projects while weaving sustainability throughout every aspect of its work. A latte in outer-space, anyone?

Speaking of which: Beyond the ELPs on college campuses, Saxbys has also partnered with community groups like the youth homeless shelter Covenant House and the Philadelphia Youth Network to employ young people who want jobs. Meaning there’s experiential learning, training and mentoring in every single café. It’s Bayer’s goal, he’s said many times over the years, to make Saxbys “the nation’s best first employer” … especially for young people who don’t necessarily have learning opportunities or career paths served up to them as a rite of passage.

Believe it or not, Saxbys’ compelling workforce development initiatives weren’t huge point-getters in the B Corp impact assessment, Bayer says: They didn’t fall neatly into an existing category. Where Saxbys shone in the certification process, he says, was in his company’s shift to focus on stakeholders and not just shareholders; in their diversity in leadership (more than half of his executive team is made up of women and/or people of color); in their sourcing (they visit every single country and producer from whom they purchase coffee, and pay almost 100 percent more than fair-trade rates); and in their social impact.

“Saxbys has been philanthropic even before we were profitable,” Bayer says. They maxed out points on this one, thanks to countless contributions to scholarships, fellowships, toy drives, donations to community partners and community organizations, and these sorts of things.

This all brings Bayer to another perk of the B Corp certification: a clear vision on what they’re going to tackle next in terms of impact. “The environmental and sustainability side of things is a great area of opportunity for us,” Bayer says. They’re not doing so bad now, he adds, but they aren’t as impactful there as they are in other areas. “So sustainability efforts are critically important to us going forward.” Same with DEI, he says. “We’re good. But we want to be exceptional. We want to break the ceiling.”

As it happens, B Corps are reassessed every three years, which means a company has a built-in chance to set goals for which they’ll be accountable. “We’ve chinned that bar, so our muscles are feeling strong right now,” Bayer says. “But we’re going to keep raising the bar on ourselves. We want to be a leader in this movement, not just a name. A leader.”

Meantime, he thinks Philly is particularly ripe for the rise of more socially-conscious businesses. “We’re the largest college town in America,” he says. “And we have so much need. It’s the kind of city where you can make a difference, move the needle.” And now, he thinks, is the moment.

“Inequality is growing,” he says. “If businesses don’t change, the inequality is going to get worse. If good businesses don’t step up as force multipliers, we’re going to go backwards.”

That is, in fact, the bottom line with Saxbys’ B Corp endeavor. It’s not just an honor, Bayer will tell you: It’s a movement, and it’s a movement that he’s evangelical about, proselytizing through his coffee business and his connection to so many young people and students, our future entrepreneurs and employers and employees. “We need the next generation of businesses big and small to make this movement not niche, but to make it the norm going forward.”