September 2, 2021: Summer had barely ended, and school had just begun, but in Wilmington, Delaware, cars were underwater. Homes were destroyed. Documents — important life documents — were gone forever. People were living in emergency shelters without knowing where they might go next. It seemed like, although federal and state responders were doing as much as they could in the wake of Hurricane Ida flooding, it was simply not enough.

Then Stacey Henry came along with an answer from the people.

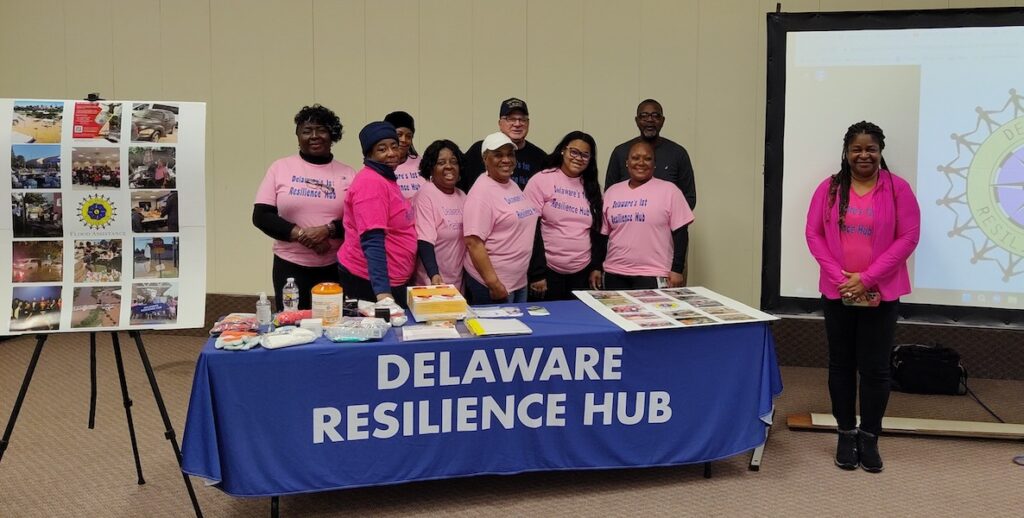

Henry is the founder of Delaware’s 1st Resilience Hub, a grassroots, “boots-on-the-ground” disaster and emergency response team that helps the community prepare, respond and recover from disasters. Henry formed the team as a direct response to the tragedy her community bore under the weight of Hurricane Ida’s torrents — but it wasn’t her intention to make it permanent.

“I didn’t go there to develop a resilience hub,” says Henry. “I went there just as a regular citizen trying to help.”

Henry cooked meals, provided transportation and resources, and advocated for people in need of shelter. Others joined in as word spread through social media. Their work has grown into the Delaware Resilience Hub that exists today.

The Delaware Resilience Hub

Henry’s team of 10 core volunteers range in age from 10 to 83. They are all certified in CPR, first aid, AED equipment and Narcan. “A lot of our trainings are to save lives,” Henry says.

They help community members find housing following displacement, and they provide emergency kits specifically tailored to individual household needs for residents to have on hand before environmental disasters like flooding strike. Kits may include 36-hour emergency candles or weatherproof folders for storing documents.

“We don’t just go into a community and say, ‘Oh, here’s a kit,’” Henry notes. Residents instead provide input and are trained on how to use the kits. After Ida, Henry and her team pinned up poster boards during a meeting and asked community members what would have helped. “Who better to tell us what to put in the kit than someone who’s been through a disaster?”

“You have to do what no one else will.— Stacey Henry, Delaware’s 1st Resilience Hub

According to Henry, she and her team have handed out over 400 emergency kits since the inception of the hub.

Members of the hub meet at least once a month to plan for upcoming events, such as tabling for Wilmington’s Earth Day celebration in order to talk about the importance of hurricane season. They work closely with the Police Athletic League of Wilmington for onsite first responder training through Federal Emergency Management Agency or the Red Cross, and for community outreach.

One of the driving forces for all of this work is the lack of effective response from government agencies in the face of persistent flooding. Climate change is bringing warmer, wetter conditions, leading to more intense storms and greater risk of flooding throughout the country. Delaware, the country’s lowest-lying state, has its own hot spots, including parts of Wilmington.

Karen Igou is a senior program manager at Wilmington’s Green Building United, a non-profit that advocates for climate-friendly development. She says the only thing protecting the northeast part of the city from the river flooding again is a tarp running across its 11th Street Bridge. “It’s not like you can’t see around the tarp,” Igou says. The city should “focus on getting the area not to flood anymore.”

Couple the dearth of effective disaster infrastructure with a high poverty rate (24 percent in Wilmington, slightly higher than Philadelphia’s 22.8 percent) and the result is a vulnerable population who have “felt ignored.”

“I think one of the things that really surprised me and everyone that was involved in our city was that everyone was expecting more. Everyone was expecting a well-oiled machine [after Ida],” Henry says. “Even years later, when those things still happen, there are constant questions about, well, How are you going to handle the next disaster?’ or, What are you going to do?”

Says Henry: “You have to do what no one else will.”

A growing phenomenon

Resilience hubs (or resilience centers) are a growing phenomenon in the U.S., following the success of Baltimore’s Community Resilience Hub Program. Ki Baja started the program in 2017 when marginalized community members expressed “having so much distrust in government for so many good reasons and feeling like they could not rely on the government for any sort of emergency services or care.”

Baja is now director of Direct Support and Innovation at the Urban Sustainability Directors Network (USDN). The USDN brings together local government sustainability practitioners representing over 250 communities across the U.S. and Canada to share best practices in climate change fortitude through the lens of mitigating historical climate inequities.

According to USDN’s resilience-hub.org, resilience hubs are defined as “community-serving facilities augmented to support residents, coordinate communication, distribute resources, and reduce carbon pollution while enhancing quality of life.” They are community centers run completely by the community itself. Each hub is unique to the community it serves but needs to meet baseline criteria: It is not run by the government; has a physical location that operates everyday, and puts people over hazards.

“When people have this social cohesion, that ability to care for each other, that is the number one indicator of people making it through disruption.” — Ki Baja, Baltimore’s Community Resilience Hub Program

“We found that when people have this social cohesion, that ability to care for each other, that is the number one indicator of people making it through disruption. It’s not whether or not they have a power system. It’s really whether or not people are checking in on them, and they’re providing that type of care,” explains Baja.

Therefore, hubs are “an opportunity [for governments] to step back and provide the resources, the funding, and the support for community to lead and manage these on their own.”

To start a hub, Baja’s team first looks for both community desire and a good physical building

for people to come together. The team then works with the community to assess what resources they already have and what they are in need of everyday, during disruption and throughout disaster recovery — the Three Resilience Hub Modes.

USDN also helps hubs find funding, which, Baja says with an air of sarcasm can be “a fun puzzle” to piece together. Funding comes mainly from federal agencies like FEMA or National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), or from city governments. (Henry says the all-volunteer Delaware Resilience Hub is funded through private donations and some public grants.)

The best way for the hubs to keep going once established is to have community buy-in. “You need to have the heart of the people in the neighborhood to be felt in the location,” says Baja. USDN sets up a community of practice when hubs express interest; but Baja is clear that that has to come from the people themselves and is set up through word-of-mouth.

Baja says a few officials in Philadelphia — including two former sustainability directors — have been in touch with USDN about helping to start resilience hubs here. Work with city officials primarily is around training them to support and trust community groups to run these spaces on their own. Turnover, including of a new mayoral administration, has proven to be an obstacle for the work to continue, and so far no community groups have reached out for advice on launching a hub here.

“That’s what I’m looking for in Philadelphia: community members that want to keep them up and going,” she says.

A “hub” of sorts in Germantown

The closest thing we have to a resilience hub is the Germantown Residents for Economic Alternatives Together (GREAT). The volunteer-based community organization was launched in 2017 by residents who were losing homes to foreclosure and gentrification. Their goal was to start a community land trust. Now, they focus on collective action — mutual aid, tool banks, cooperative farming and the like — to better their neighborhood.

Germantown also faces frequent flood threats, during which low-income households are particularly vulnerable. “We have quite a few folks living in poverty who have difficulty accessing flood insurance. Or people can’t afford to pay for the damage that’s done to their homes over time,” says Marie-Monique Marthol, GREAT Steering Committee and Emergency Prep Working Group member. “When people are living on the edge financially, on a daily basis, any additional costs can mean the difference between being able to stay in your home — and not.”

“We have to rely and trust on and develop systems for ourselves that are hyperlocal. If we are to survive, it’s going to be together.” — Marie-Monique Marthol, Germantown Residents for Economic Alternatives Together

Unlike the Delaware Resilience Hub, the Emergency Prep Working Group is just one of GREAT’s committees. It began following disruptions in the supply chain — lack of groceries and medical supplies — during Covid, says Marthol.

She agrees with Stacey Henry that, during a disaster, governmental agencies may not do enough. “And so we have to rely and trust on and develop systems for ourselves that are hyperlocal,” she says. “If we are to survive, it’s going to be together.”

The Emergency Prep team offers programming to meet community-identified needs: fire safety and prevention workshops and literature; flood resilience films; and potable water sources education and events. One of their most comprehensive resources is their Emergency Preparedness & Community Self-Reliance ~ Organizer’s Guide. The guide covers topics from how to work with neighbors to practical tips for short-term and long-term disaster resiliency.

“We know that one of the most important things to do or to have established during an emergency or disaster is your connection with your neighbors,” says Marthol. “We talk about emergency preparedness through the lens of knowing who your immediate neighbors are, having established a degree of trust and connection with your neighbors. So that when an emergency situation occurs, we know that we are resources for one another.”