Philadelphia’s next mayor will confront urgent challenges: dramatically lowering gun violence while restoring public safety and civility through revived community policing; reducing poverty and associated inequities in schools, housing and addiction rates; restoring optimism and momentum, sapped by despondency and the pandemic hangover.

Progress can be made by this administration in the next 16 months. But candidates who wish to lead in 2024 will be judged by their ability to offer coherent, compelling and practical solutions they can fund, deliver, and sustain over four years.

We should expect nothing less. An old adage however, is worth repeating: “Don’t let the urgent distract from the truly important.” Anyone who attends neighborhood meetings knows that’s easier said than done. Communities are anxious and angry; they demand solutions now. But beneath the urgent looms a deeper challenge that, if unsolved, constrains all the rest.

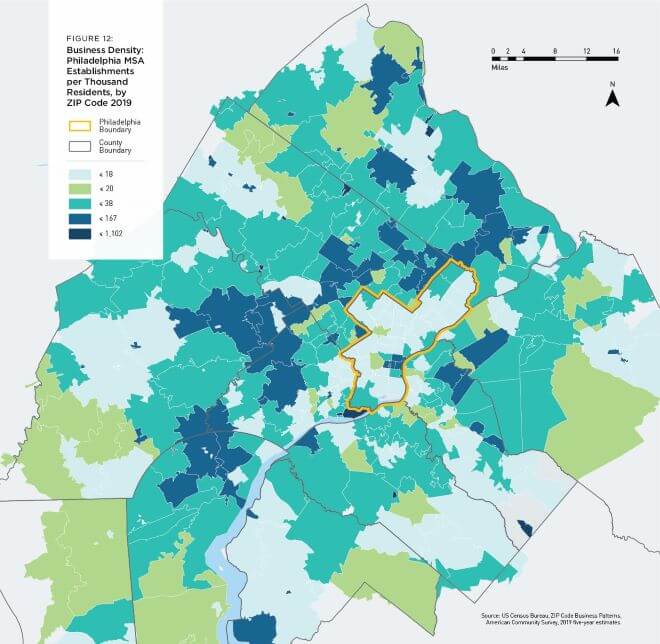

As shown in a recent Center City District report, this regional map depicts the limited clusters of jobs in Philadelphia: Center City, University City, East Falls, the far Northeast and Northwest, the airport and Navy Yard. Even more telling are the blank spaces: vast swaths of the city lacking many jobs, in sharp contrast to the suburbs.

Decades of decline left Philadelphia with fewer jobs and businesses per resident than comparable cities and our own suburbs. Make no mistake, we have achieved great success: a thriving downtown, a burgeoning University City and Navy Yard, vibrant commercial corridors, world-class educational and cultural institutions and surging investments in life sciences. But it’s incomplete. There are still insufficient employment opportunities, particularly for those without cars.

Hospitality, education and health care are our strong suits. But there are not enough businesses selling services on a national or global scale, paying family-sustaining wages and driving demand for emerging Brown- and Black-owned businesses. These major employers flourish in peer cities and surrounding counties, but not in Philadelphia. Their absence weakens our tax base, eroding the ability to fund services to solve problems.

This wasn’t always the case. At the start of the 20th century, Philadelphia had 16,000 manufacturers producing and exporting nationally — locomotives, ships, radios, hats, carpets, men’s and women’s clothing and refined sugar. Termed “traded industries,” these enterprises hired 250,000 skilled laborers who created products for export and drove demand for local businesses to support their production processes, giving the city the moniker “the workshop of the world.” By the end of the 20th century, nearly all were gone.

Only one among the 10 largest employers in the city are taxable private sector firms. These businesses are present in the region but not in the city. We are like a six-cylinder car engine firing on only two of its cylinders.

Philadelphia’s experience wasn’t unique. Most peer cities suffered industrial decline by the end of the 20th century. What’s different is that others rebounded robustly after 2000 with post-industrial jobs. For cities examined in this Center City District study, the first decades of the 21st century were a time of vigorous expansion: New York City’s job growth was 23 percent; San Francisco, 21 percent; Denver, 15 percent; Boston, 14 percent; Philadelphia’s growth was just 7 percent. In 2020, just before the pandemic, many peer cities recovered so successfully that they held more jobs than they did in 1970; Philadelphia had 22 percent fewer jobs. Moreover, the jobs we grew were concentrated in low-wage sectors.

Post-industrial “trade” is hard to visualize. When businesses sell outside the region, you don’t see crates of cargo on ships sailing down the Delaware. But, when an advertising or engineering firm contracts with a client in Chicago, Miami or London, that is traded sector activity, enabling them to hire local staff, buy more workstations, supplies and purchase services from local lawyers and accountants. Their employees patronize restaurants, dry cleaners and shoemakers, take SEPTA, cabs, Uber and Lyft — spurring local sector activity. During the pandemic, we saw the impact when big employers closed: smaller suppliers and those without the luxury of remote options — restaurants, janitors and building maintenance staff — all lost their jobs.

Sadly, this has been happening for some time, only in slow motion. Between 1975 and 2016, Philadelphia lost more than a third of jobs in finance, insurance and real estate. Figure 5 from the report compares us to other cities.

The post-industrial economy, enabled by digital technology, is bursting with “traded” establishments that offer high-wage, family-sustaining and entry-level jobs. Figure 6 tracks trends from 1998 to 2016 among urban-based, professional and business services firms that sell nationally and globally. It’s an even more distressing contrast.

To bring home the value of hosting traded sector establishments, consider the huge presence of information companies in San Francisco (Figure 11). Every Philadelphia resident and business using Apple, Dropbox, Facebook, Google, Intel, Salesforce, Oracle or Uber is transferring money to support traded firms and employment in the Bay Area. Considering scientists at the University of Pennsylvania invented the first computer, ENIAC, it underscores the benefit of capturing local innovation and translating it into more Philadelphia-based traded industries — something we are just starting to do with life sciences.

There are six broad categories of employers who flock to cities. Philadelphia lags in four of them, particularly among traded sector establishments offering good-paying jobs in information, financial, professional, technical and business services. Figure 7 in the report underscores that only one among the 10 largest employers in the city are taxable private sector firms. These businesses are present in the region but not in the city. We are like a six-cylinder car engine firing on only two of its cylinders.

The two standout exceptions are education/health care and hospitality. The first sector is largely exempt from Philadelphia’s real estate and business taxes. The second nationally pays lower wages on average than other industries and is thus less impacted by the wage tax.

Philadelphia can be proud of decades of commitment by five mayors to the hospitality industry, building on historic assets and providing opportunities for local residents who lack college degrees. However, it is now widely understood that Philadelphia excels in the growth of entry-level jobs, but falls far short with family-sustaining jobs.

Figure 10 shows the difference in wages paid within the same sector by Philadelphia firms that sell only locally and those with national and global reach. Many of these sectors contracted, especially the traded portions that pay best wages.

Success in hospitality has been achieved by major capital investments in the convention center, arts, cultural and sports facilities, as well as a dedicated hotel tax that supports marketing for conventions, trade shows and tourism. This spurred construction jobs, an 80 percent increase in leisure and hospitality employment and the formation of new local businesses, like restaurants and event promoters. If we can do so well in hospitality, what will it take to succeed in other sectors?

Post-industrial firms with more family-sustaining jobs are actually less expensive to attract since they require few targeted municipal, capital investments. They value what benefits all residents and businesses: investments in transportation infrastructure, public safety, sanitation, schools and amenities.

Because they sell to very broad markets, these firms can locate almost anywhere. Situated in our suburbs, they still access our workforce; 35 percent of working residents in each City Council district already reverse commute. To locate within Philadelphia, these firms require more competitive taxes, especially when hybrid and remote work enables suburban residents, who are directed to work from home, to get a 3.8 percent raise, as they become exempt from our wage tax.

In June 2022, Philadelphia City Council reached a new consensus that lower wage and business taxes support the growth of Black- and Brown-owned establishments and neighborhood small businesses, fostering more job opportunities.

But smaller businesses can’t reach their full potential, nor will we generate enough family-sustaining jobs, without taking the next essential step: creating a more competitive setting so medium-sized and larger establishments that sell externally choose to locate and grow here, contracting with local small businesses. Cities that have done so have lower unemployment and poverty, more family-sustaining jobs and a prosperous network of small, local businesses.

It’s a tall order for the next mayor. Steadily lower wage and business taxes to encourage growth of existing firms and draw new ones to the city where they will benefit by being at the center of our regional transit system, access a skilled workforce and enjoy remarkable amenities. Devote the same energy we commit to conventions, festivals and sports to retaining and attracting businesses that sell nationally and globally, especially the life sciences. Do this and we expand the real estate tax base of the city and can afford to fund the services we need. (Even hybrid businesses need a headquarters for gathering, collaboration, mentoring and innovation). Public safety is paramount, as are clean streets, quality parks and schools. But without more jobs, many Philadelphians have no future.

Paul R. Levy is President & CEO of Center City District. This article summarizes the findings of a report that the Center City District has just released, Firing On All Cylinders: Growing Jobs and Small Businesses by Expanding the Traded Sector, available on CCD’s website.

The Citizen welcomes guest commentary from community members who stipulate to the best of their ability that it is fact-based and non-defamatory.

MOST POPULAR ON THE CITIZEN