Malcolm X began wearing glasses during a stint in prison. Before that, he had no reason to. X dropped out of school in eighth grade — and didn’t read for over a decade, until he ended up in the library at Norfolk Prison. There he taught himself, beginning with rote transcription from the dictionary, and ultimately developing a passion for reading that consumed his every moment. His signature glasses were the product of late nights spent nose-deep in a book; he filled his correspondence with family with requests for new books.

Encountering literature catalyzed X’s metamorphosis into an intellectual figure. As he wrote in his autobiography, “No university would ask any student to devour literature as I did when this new world opened to me, of being able to read and understand.”

For the over 1.9 million Americans currently behind bars, books can be a lifeline. Books connect inmates to the world outside prison walls. They teach new skills. They ignite the imagination and beget self-reflection. Books in prison do what they do everywhere: Transport the reader beyond their own reality towards something more.

“I’ve had people tell me, I never read a book cover to cover until I got your books.” — Tom Haney

The entrance to Books Through Bars.As prison budget cuts deplete rehabilitative and educational programs, books have become even more essential. Studies show that literature has rehabilitative effects and decreases rates of recidivism. Reduced recidivism, meanwhile, means less crime, safer neighborhoods, and less cost to taxpayers.

However, since the mid-20th century, access to reading material on the inside has gotten more difficult. While Malcolm X could go to the prison library and/or receive books mailed by family, today’s prison libraries have been neglected to the point of decimation.

In the face of what could become tantamount to America’s largest de facto book ban, a small organization in West Philly has worked to bridge the gap, providing free books to prisoners across Pennsylvania and other Mid-Atlantic states, since 1990. The premise of Books Through Bars (BTB) is simple: Everyone deserves a chance to read.

“I don’t know about you, but when I get into a good book, I get lost in the characters,” says Tom Haney, a long-term volunteer at BTB. “So this helps folks on the inside to get lost in those characters, get out of the horrible things that are going on around them while they’re incarcerated, and hopefully that is part of our way of helping people learn to read or to write.”

A West Philadelphia institution

BTB shares a Baltimore Avenue rowhouse auspiciously adorned with a colorful outdoor mural with parallel community projects, including Prison Health News and Address This, a correspondence education program. At one point, an anarchist commune was based here too. On a November morning, the space is alive with dozens of people.

“Does anyone know where the erotica is?” calls out a gray-haired woman. The volunteers are split in two. Some are collecting requests from the shelves; others are cutting up paper bags to repurpose as packaging paper. Erotica, it is announced, is catty-corner to the world history books. Rolling up the sleeves of her blazer, the volunteer beelines towards her treasure, nearly knocking over a man balancing a stack of science textbooks. With one hand, she carefully pulls out a promising book while holding onto a letter from an inmate in the other.

At its foundation, BTB is a mail-in operation. In 2023, BTB received over 5,500 letters from inmates — out of over 66,000 letters since 1990. Some correspondence is long, listing books their sender has read and anecdotes alongside, while other letters are brief and perfunctory, but across the various genres, interests, and reading levels, the people writing to BTB are looking for one thing: books.

BTB volunteers read each letter and then fulfill the book requests, mailing out around three to five books per package for inmates to keep and share. The operation is entirely volunteer-led, involving mostly West Philly community members. On this day, college students, a church group, and a couple of friends comprise the crew. Some are joining for the first time; others have made volunteering with BTB part of their weekend ritual.

A group of new volunteers winds through a backroom labyrinth of bookshelves and ducks under a door frame on their way down to the equally packed basement. Despite the sheer quantity of books, everything is carefully categorized, from various types of fiction to different religious texts.

BTB receives most of their books through donations. The sources vary: estate sales, church book drives, bankrupt publishers. Law books from a local firm that moved locations fill a back shed. More stand in grocery bags, a morning donation. Sorting through their loot, someone exclaims with excitement upon finding a stack of National Geographics, which were banned in a number of prisons until recently.

“Cramming this many books into a West Philly rowhouse is kind of a horror show,” says Mark Blaho, who has been volunteering with BTB for a little over a year now.

“It’s kind of a feat,” retorts a fellow volunteer who goes by LJ as they stabilize the bags on top of a mountain of unsorted donations.

“You name it. It’s like working for a public library because, guess what: They are the public.” — Stephanie Riley

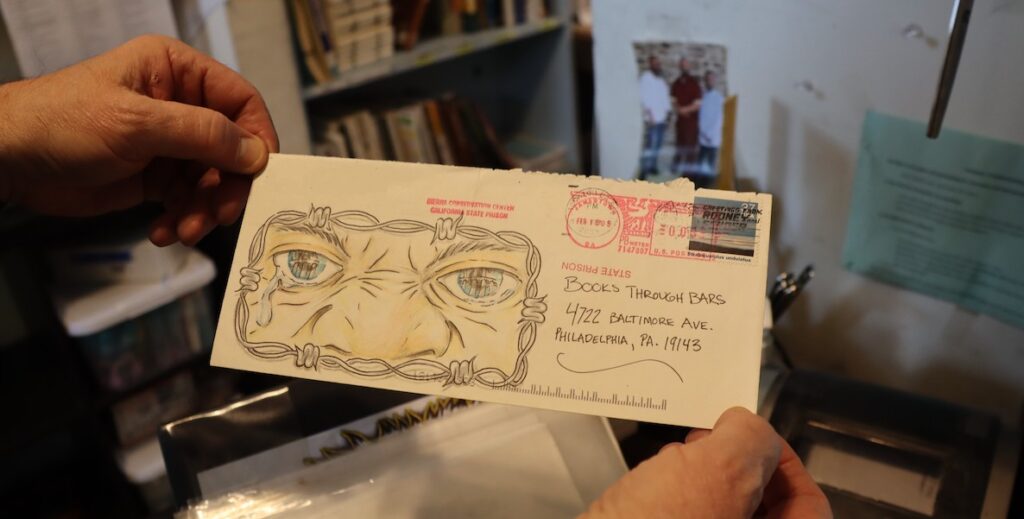

The only room without bookshelves is the foyer. Here a dozen or so pieces of inmate-made artwork — all tokens of gratitude — line the walls. Some are detailed line drawings, depicting a mastery of technique and style, while others are abstract. All offer insight to the lived reality of incarceration. These pieces are far from all the work they’ve received over the years; an exhibition of that size would require a gallery twice as large.

A few years ago, Book Through Bars coordinated the sale of inmates’ artworks and distributed the funds to inmates’ accounts. Now, however, with many prison creative programs shut down, few individuals have access to the resources for art. Still, inmates decorate the envelopes they send to BTB with sketches and insignias of self-expression.

Books in the era of mass incarceration

As prison policy has changed, so has BTB. BTB started off serving all 50 states. Today, having built relationships with similar organizations across the country, they specifically serve prisons in the Mid-Atlantic, from Pennsylvania to Virginia. In total, they reach somewhere around 460 institutions, but while BTB prides itself on their expansive services, their growth isn’t something they celebrate.

“Jeez, it’s almost like the United States has a mass incarceration problem,” says Blaho, as he counts through the pages of prisons that they currently service. “It’s gross.”

Mass incarceration is largely to blame for the lack of books in prisons. Prisons simply haven’t been able to keep their services on pace with growing carceral populations. Some prison libraries are simply closets of tattered books that haven’t been updated in decades.

Many prisons have established mailroom restrictions in response to increased concerns about contraband and drug overdoses. In PA, as in many states, inmates can’t receive packages mailed by friends and family, as they did for years. Eighty percent of U.S. prisons require books come in through a third party — like BTB.

In 2018, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania briefly banned receipt of all packages after one prison received a book laced with a methadone-like drug. The ban was eventually lifted after intensive organizing, driven in part by BTB. Still, prison mailrooms heavily regulate the influx of material, leaving censorship up to individual mail sorters. Some prisons outlaw secondhand books, and others go as far as to ban chemistry and other science textbooks.

Such practices regulate ideas only. Most illegal drugs enter prisons via staff.

In this context, BTB has been invaluable. “We usually say, organizations like Books Through Bars supply most of the books to prison libraries because when an inmate is finished with it, it gets passed around amongst other inmates but eventually makes its way right to the library,” says Haney.

Although BTB shows up on prison handouts, many inmates learn about their work from someone else on the block. Many request books from BTB multiple times — one particular individual submitted nearly 50 book requests. Thrillers and mysteries are particularly popular, but requests can run the gamut, from legal texts to fantasy.

“People always ask what sort of books inmates ask for,” says Stephanie Riley, a long-term volunteer and the office manager of BTB. “You name it. It’s like working for a public library because, guess what: They are the public.”

The people behind Books Through Bars

As it happens, Riley is a professional librarian by day, as are a number of other volunteers who work with BTB. However, the makeup of the core volunteer staff varies widely. Haney left law enforcement after he grew disillusioned with the nature of his work, went on to pursue a doctorate in divinity, and returned to prisons as a counselor before retiring and joining BTB.

LJ was arrested in 2017 and ended up at Books Through Bars as part of required community service — only to fall in love with the work. Now, they volunteer around three times a week for 3 to 6 hours each time. “I touched more books in the last four years of my life than I did the entire other 24 years of my life,” they say.

There’s no full-time staff. Instead, a tight-knit group of committed “core volunteers” like Haney and Riley lead BTB, running the organization as a collective, without official leadership positions beyond the teasing nicknames they throw at each other while sorting books in the backroom.

“This is my family,” says Haney, pointing to the core volunteers folding letters for a fundraising campaign as 90s pop plays. LJ ducks inside with their bike, shaking off the rain, and the group cheers their arrival. There is a love for each other and their cause that permeates the space. Core volunteers treat the organization as a second calling, coming in on the evenings and weekends to coordinate the logistics required to make sure books safely reach their intended audience — people who, by definition, are isolated from friends and family, receiving often infrequent 15-minute visits, with limited — and expensive — access to phone communication.

For some inmates, correspondence with BTB is their sole connection beyond prison — a responsibility the organization takes seriously. “We take certain steps to make it more personable,” says Blaho, “to let them know that a person took time to pick out the books, read the letter, and write out the invoice.”

Vital correspondence

Originally a prison regulation for detailing the contents of incoming packages, BTB reclaimed the basic invoice as a way to send personalized notes with their books.“Just the little things that can make someone’s day,” explains Blaho while preparing a book for shipment. Invoices include a short note about the books they received, phrases of solidarity, or even just a smiley face.

BTB receives hundreds of thank-you notes from inmates each year. People send artwork, stories, or reflections inspired by the books they received. The appreciation is not only for the books themselves but also for the care and recognition BTB provides. Every inmate who sends BTB a thank-you note receives a response from Haney himself. “I’ve had people tell me, I never read a book cover to cover until I got your books,” says Haney.

I had read plenty of books before, but it’s nothing like reading people’s letters,” — Katie Rawson

Many individuals enter prison having been neglected by the educational system; as a result, dictionaries and textbooks are some of the most common requests.

Haney brims with excitement talking about a particularly moving letter BTB received this month. An inmate shared that through BTB, he studied and passed his GED exam, attaching his transcript. Now, he was inquiring about SAT books.

To Books Though Bars,

I received your package of books. I requested a dictionary and related vocabulary material. I wanted to thank whomever I should of your program because it really was incredible to me what I got. I was surprised you came through and the quality of the dictionary is great! Plus, the thesaurus and other vocabulary books were great as well. Brand new, too. Also surprising was a Tupac music magazine which I didn’t request and can’t believe because I am a big 2Pac fan! I was just the previous day before receiving the package trying to figure out a word in regards to 2Pac and what “acronym” meant because 2Pac came up with something called “T.H.U.G L.I.F.E” and the next day I get a dictionary to look up the word and a Tupac magazine! So thank you so much and you made the rest of my bid. Keep doing what you’re doing. I’m getting out in July 2023 and you helped a lot.

“[BTB] totally transformed how I think about prison in the U.S. I had read plenty of books before, but it’s nothing like reading people’s letters,” says Katie Rawson, a BTB volunteer and university librarian with a PhD in American studies.

“Reading the letters just brings it close to home and makes it personal,” adds Riley. Some of the most heartbreaking letters, she notes, are lists of children’s books or parenting manuals — a reminder that the American prison system has separated nearly 5 million children from their families.

Every volunteer is assigned a letter. They rush to action to construct the perfect collection of books. A man behind me asks a core volunteer, “What’s manga?” and she guides him to the basement shelf of graphic novels explaining the Japanese form. Throughout the selection process, this volunteer is in conversation with the person behind the letter: They learn from and about each other through a stack of books. Even something as brief as a list of genres reflects the intimacies of someone’s life with all their curiosity, passion and aspirations.

Carefully, I open my own envelope and unfold a thin piece of lined notebook paper. It strikes me that the handwriting on my envelope looks like my mom’s, with the same subtle loop of each ‘m’ and the randomly interspersed capital letters that characterized my elementary school sick notes. The author of this letter could very well have been someone’s mom.

I wouldn’t know; all I had in my hands was a list, signed off with a brief thanks.

Fulfilling a letter request is an intimate responsibility. How do you pick a book for someone, when that is their only means of escape? Walking by the shelves of cramped covers and askew titles, I run my finger along the edge of each book spine. I try to consider everything: reading level, interest, relevance. I imagine the recipient of these books peeling apart and opening their covers in a space entirely different from mine — perhaps a prison cell or rec room — and discovering their own world in these fragile pages.

Finally, I assemble a collection of five books that match their interests, including one of my favorites — The Autobiography of Malcolm X. I hand them over to another volunteer who wraps them and signs off: Love, Books Through Bars.

Norah Rami is a student at the University of Pennsylvania where she is the Digital Managing Editor at 34th Street Magazine. Her words can be found in The New York Times, Teen Vogue Magazine, and the Philadelphia Obituary Project.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story named the wrong doctorate for Tom Haney.

MORE ON PRISONS AND PRISON REFORM