Last weekend, there in the pages of The New York Times, was an advertisement for the good ol’ Philly Shrug, courtesy of our mayor. In the aftermath of the South Street mass shooting, Jim Kenney — out of town for a U.S. Conference of Mayors meeting — seemed neither pissed nor resolute. Instead, he projected resignation, offering that there was little he could say or do to reassure a city of scared citizens in the face of legislative inaction on gun control from Harrisburg and Washington.

“Words are hard,” Kenney said. “Words these days have become somewhat meaningless. Hearts and prayers, and prayers and condolences, it doesn’t work anymore. It just doesn’t work. And again, the frustration for me is I would like to be able to do something about it.”

On one level, he’s right. The “thoughts and prayers” refrain has become a signpost of hypocrisy and callousness. So, yes, words are hard — but exclamations from leaders about how inadequate more talk is are usually followed by bold calls for action, as we see across the nation in cities like St. Louis, New York, Chicago and, even closer to home, Chester. Not from our mayor, however.

“The mayor is not interested in any kind of broad partnership among many agencies, that collaboration that has worked in Chester,” Haywood announced after meeting with Kenney. “He’s not ready for it. Obviously this is very disappointing.”

Not everyone is helpless

But Kenney’s not alone in projecting an air of helplessness. I recently spoke to one elected official who actually threw up his hands: “I’m supposed to cure gun violence?” he said, “I can’t make the mayor and district attorney speak to one another.”

Meanwhile, while the body bags pile up, the blame game is played. Kenney bashes Harrisburg and (rightly) second-guesses District Attorney Larry Krasner’s lenient charging decisions. Krasner, who has presided over a steep decline in gun prosecutions and reform-minded court diversions (arrests that feed offenders into treatment in lieu of prosecution), creatively pivots to Trump and what he has wrought.

Talk about a flurry of meaningless words. If you’re a citizen of Philadelphia, you’d be justified in wondering why our leaders stick to what hasn’t worked while Philly burns.

There are two elected leaders who, it appears, have embraced action over more of the same. One is Congressman Dwight Evans, who, back in April, announced a (still-unfunded) $51 billion plan to tackle the nation’s gun violence epidemic at its roots, and who last month urged the mayor and Council President Clarke to use some of the city’s $800 million in untapped American Rescue Plan funds to enact his seven-point plan, which includes investing in proven policing strategies like focused deterrence, hot spot and problem-oriented policing, as well as the hiring of more cops. (We’re down close to 1,000 officers.)

2022.05.05 Letter to Mayor and Council President on Community ViolenceArt Haywood, dogged optimist

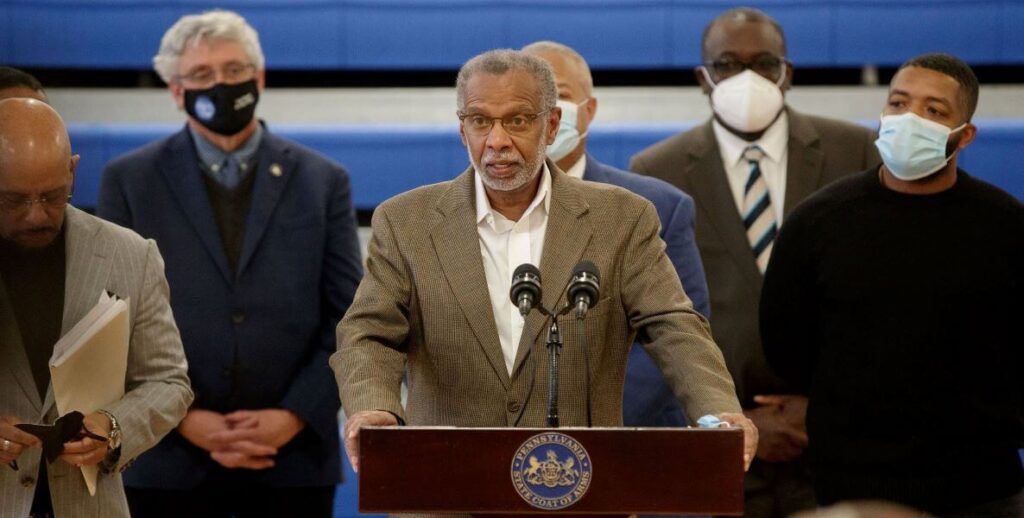

Little-known State Senator Art Haywood has also approached the scourge of gun violence like the all-hands-on-deck crisis it is. Haywood, who represents parts of Northwest Philly and eastern Montgomery County, came to elected office relatively late in life — he’s now 65. He’d long been an attorney representing affordable housing nonprofits when, inspired by Barack Obama’s underdog 2008 campaign, he won a seat on the Cheltenham Township Board of Commissioners. In 2014, he defied the odds and won his state senate seat. “Even my friends thought I was crazy for running,” he said when I caught up with him this week.

But Obama, he says, had taught him that all things are possible, a doggedly optimistic sense he’s taken into the battle against gun violence. While Kenney and Krasner and so many other buck-passing elected officials float the fiction that exploding gun violence is a national phenomenon and that localities are constrained from making their communities safer, Haywood’s research finds cities across the nation that have bucked the national trend.

“A point of breakthrough was when my staff saw data earlier this year about six or so cities — St. Louis, Jacksonville, Miami, Chester — that have reduced gun violence,” Haywood told me. “Yes, there’s racism and poverty. But there are cities who are moving the needle on gun violence, and all along my position has been, Let’s take what works in those cities and apply it to Philadelphia.”

Other cities have reduced gun violence. Why can’t we?

In virtually every city Haywood and his team studied, a mayor had convened a task force of law enforcement and social service leaders that meets weekly to coordinate a whole government approach to gun violence. That’s what has worked in Chester, for example, where there’s been a momentous 36 percent drop in the murder rate: The mayor, DA, police chief, public defender, and social services providers put aside egos and political differences and are all part of the same team.

Haywood drew up a letter to Mayor Kenney with a seven-point plan, including the establishment of a multi-agency task force that would meet weekly and coordinate all gun violence interventions at a top level, and requested a meeting with the mayor. Twice, he hand-delivered the letter to Kenney when he quite purposefully ran into the mayor at public events. Despite pledging to get back to the senator, Haywood says, Kenney never did.

Undeterred, Haywood began meeting with Councilmembers, staffers from the DA and AG offices, respectively, and others — getting commitments to take part in such an all-hands-on-deck approach. But studying other cities, he knew how hard it would be to move the needle without a mayor’s involvement. Finally, last summer, he released the letter to Kenney publicly, which got a tepid response — some boilerplate language about working together. But still no meeting date. Haywood kept meeting with the mayor’s staff, but, after months of being put off, it became clear he wouldn’t be granted an audience. By February of this year, there was still no response to his request for a face-to-face.

“This is the civil rights battle of our lifetime, dealing with how guns are destroying not only individuals, but are destroying the anatomy of our cities and our communities,” New York Mayor Adams has said.

Some of his staffers, Haywood said, took the mayor’s refusal to meet as a slap in the face, but Haywood resisted the urge to make it personal. “The mayor has a lot on his plate,” Haywood would remind his staff, but he also knew he had a built-in advantage: As a still-relatively new elected official at the ripe old age of 65, he wasn’t hampered by ambition. “I have a lot more freedom than those who are looking to run for their next job,” he told me.

For months, Haywood had tried to avoid turning a desire to stem the tide of gun violence into a public pissing match with the mayor. But in April, he concluded he had no choice. In concert with a group of gun violence activists, Art Haywood sat-in outside the mayor’s City Hall office. You would think that a state senator protesting outside a mayor’s office might make headlines, but it was a fleeting story. Nonetheless, it finally got Haywood his meeting with Kenney and the mayor’s law enforcement and gun violence staff.

Here’s where you might expect a happy ending, all protagonists emerging and announcing they’d reached some common ground. But Jim Kenney is not that type of practical problem-solver. The meeting, by Haywood’s account, did not go well. A mayoral staffer dismissed out of hand Haywood’s primary “demand” — the formation of that multi-agency, cross-sectional task force — while the mayor remained mum.

The administration seemed open to two of Haywood’s planks — hiring more violence interrupters on the street and embarking on a street-cleaning program with Morgan Berman’s innovative Glitter app — but mostly there was no sense of banding together to try out new solutions at a time of existential crisis. “The mayor is not interested in any kind of broad partnership among many agencies, that collaboration that has worked in Chester,” Haywood announced afterwards on Facebook Live. “He’s not ready for it. Obviously this is very disappointing.”

Haywood, though remarkably even-keeled, projects a strong will. He’s pivoted to seeing what he can do at the state level to get around Kenney’s inaction. Funding a Glitter pilot, investing in CURE Violence-like violence interrupters as in New York City, and fueling a Neighbor to Neighbor mental health services program are all on his agenda, as is drafting legislation to form the type of multi-agency task force the mayor is resisting.

But he knows that, if you don’t have all the players on board, the chances of ultimate success are slim to none. It just may be that Art Haywood has learned that you can’t mandate that others share your sense of urgency.

Throughout the nation, other mayors are reacting to crises by trying new things.

In Chicago, Mayor Lori Lightfoot has talked about suing gang members, seizing their weapons, money and vehicles. In New York, Mayor Eric Adams has been the anti-Kenney, flooding the airwaves with new programs, reviving an anti-gun police unit his predecessor had disbanded, and deploying more officers to the subway system. Last week, he announced a Haywood-like gun violence prevention task force; while New York is still a shooting gallery and Adams’ poll numbers are slipping, there’s no question that the guy is on the case and making public safety job one.

He even talks about his mission in a very un-Kenney like way. Rather than bemoan what he can’t do, he defines the stakes: “This is the civil rights battle of our lifetime, dealing with how guns are destroying not only individuals, but are destroying the anatomy of our cities and our communities,” Adams has said.

Adams and other mayors have shifted to crisis management mode. They establish command centers, deploy task forces, and mobilize the business, nonprofit and religious sectors to step up to the moment. Even then, success is not assured, as Adams may be finding out.

But isn’t leadership about grabbing the wheel when the car is careening out of control? Or is it about soliloquizing over the faulty brake system while driving into a ditch? Yes, Harrisburg preempts Philly from enacting its own gun laws. Yes, Congress can’t pass gun control legislation. Yes, as Haywood points out, racism and poverty abound.

But even with all that, it’s fair to ask those who knew the job was dangerous but asked to lead us anyway: What’s your plan? When what you’ve been doing ain’t working, what else you got?

RELATED POSTS ABOUT GUN VIOLENCE FROM THE CITIZEN